On March 16, a white man killed eight people, including six Asian American women, in a series of mass shootings in Atlanta. Occurring amid a reported nationwide rise in anti-Asian violence, the attacks have left many across the country shaken and grieving, including those in the Princeton community. They also shed light on the ever-present, but often under-discussed, history of anti-Asian racism in the United States and discrimination that Asian and Asian American people face in their day-to-day lives. Even as many have rallied in support of Asian communities since the events in Atlanta, we have witnessed more senseless and violent attacks.

Amid these events, we have seen statements of solidarity and acknowledgment from the University, departments, and student groups. These actions are necessary, but, when left only as words, do little.

The University community must ensure that the history and experiences of Asian Americans and other marginalized groups are not overlooked in academic settings. It must also take more specific action to accommodate rather than simply acknowledge, the broader swath of suffering students.

This Board calls on the University community to back up their statements of solidarity with action.

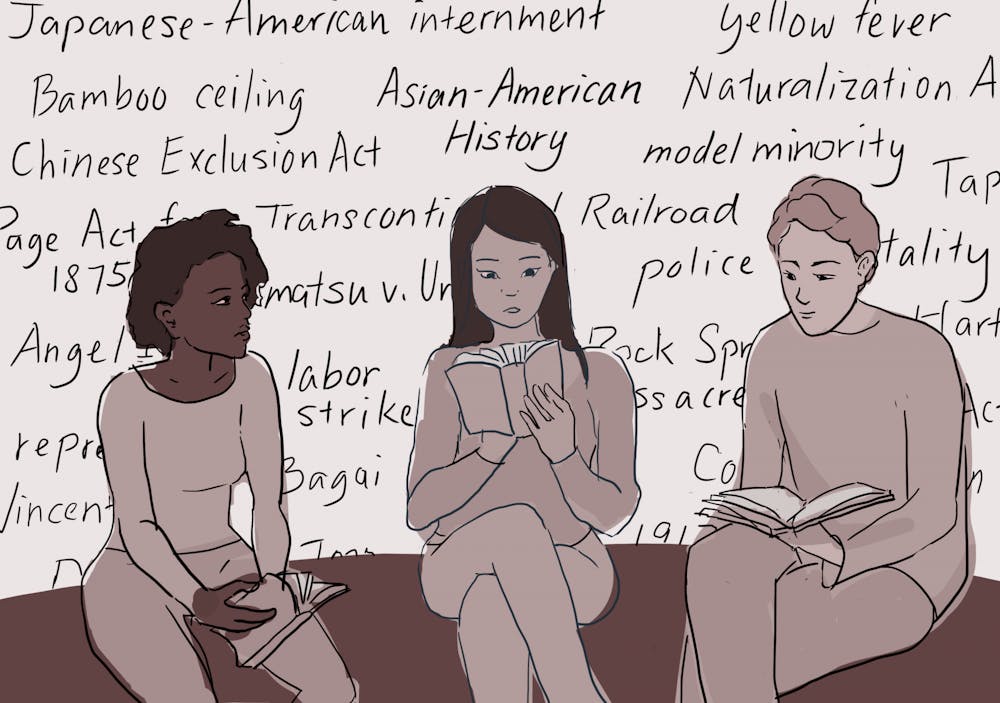

Education and the history of anti-Asian discrimination

Although anti-Asian racism has become more visible due to dangerous rhetoric around the COVID-19 pandemic, anti-Asian discrimination and violence in this country are not new. Since the events in Atlanta, a number of community members have highlighted this history.

History professor Beth Lew-Williams pointed to the 19th-century origins of anti-Asian violence in America manifesting in massacres of Chinese people through the 1870s and 1880s. Her colleague, professor Kevin Kruse emphasized a more recent incident, writing on the 1982 killing of Vincent Chin, a Chinese American man, and the parallels between that instance and the massacre in Atlanta. And amid a tragedy where race and gender are clearly intertwined, English professor Anne Cheng examined the historic intersection of misogyny and anti-Asian racism.

As Lew-Williams, Kruse, Cheng, and a number of other scholars demonstrate, there is a wealth of knowledge on this topic at the University. Instructors should make use of these, and other resources, in their classes in order to consider the role that race, including Asian and Asian American identities, plays in their respective disciplines. Some professors already do so. For example, African American Studies professor Imani Perry explained on Twitter that she always teaches Asian American history in her course on race in legal history. “You cannot teach serious history of US law as an instrument of racial injustice without the history of Asian Americans,” she wrote.

In the meantime, students must take action. We must educate ourselves on the history and current state of the Asian American experience; as most of our curricula stand, no one is going to do that for us.

Return to the Princeton voices resource, and find out who on campus can be a valuable resource. Take a class or two with them. As course selection for Fall 2021 approaches, consider how you may incorporate learning from the Program in Asian American Studies.

Beyond education: The importance of taking action

These educational considerations are important in generating awareness about Asian and Asian American experiences, both historical and modern. But “standing in solidarity with our Asian American community,” as University President Christopher Eisgruber ’83 titles his statement, necessarily involves more than just education.

As students, this requires us to be active bystanders, not only when violence is imminent, but also in conversations about race. The Princeton Asian American Student Association (AASA) has compiled resources, which any Princeton student can access, related not only to education but also to mental health and showing solidarity — financial and otherwise. As our community reels from the attacks in Atlanta, we must incorporate what we learn into what we do.

The University must also do more to take into account the mental toll that traumatic events like these can have on students. As Jennifer Lee ’23, co-president of AASA, told The Daily Princetonian in the wake of the Atlanta shootings, “Our Asian and Asian American communities are in so much pain right now.”

Editor-in-Chief Emma Treadway wrote recently about how the pandemic has held students “in a state of ambiguous loss, and we are unable to properly mourn as we remain in the midst of uncertainty.”

As Julia Chaffers explains, endless hours online, shortened breaks, and lack of extracurricular support this semester has left students burnt out. The increases in racialized violence and its reporting, beginning at least with last summer, have an undeniable effect as well.

While President Eisgruber has expressed his solidarity with Asian students, and the University at large has emphasized the importance of mental health through email and social media campaigns, this is not enough.

“Trite emails about staying positive and finding time to care for yourself don’t change the lived realities students face, unless they can be used as a pass for an extension or absence from class,” Chaffers wrote.

Claims to care about the Asian American community and students’ mental health at large must be supported by lenience, respite, and forgiveness. We appreciate the instructors who have understood this, adjusted expectations, and taken the initiative to be candid about the impact of this period of loss on the mental health of students, faculty, and staff alike.

We strongly urge the entire University community to rise to the occasion. This means affording each other the necessary grace to prioritize mental health as we all try to reckon with the relentless violence and loss of the past year. It also means not shying away from conversations about DEI, no matter the discipline, and intently educating ourselves about the persistence of anti-Asian violence in America and systemic racism at large. As Kirsten Pardo ’24 told a reporter at a Stop Asian Hate rally in Princeton, “You have to acknowledge a problem first before you can actually fix it.”

Maybe then can our community finally start to heal.

145th Editorial Board

Chair

Mollika Jai Singh ’24

Members

Shannon Chaffers ’22

Won-Jae Chang ’24

Kristal Grant ’24

Harsimran Makkad ’22

Anna McGee ’22

Collin Riggins ’24

Zachary Shevin ’22