As the days warm up, the nights are becoming less intolerably freezing, so take advantage of the start of spring by heading out for some stargazing next time the skies are clear. If you’re on or near Princeton’s campus, consider this a starter guide to the April night sky.

It’s been getting dark around 7:30 p.m. on campus lately, but you’re best off waiting a few hours past twilight. Anytime after 10 p.m. is perfect; it’s not like you’re sleeping anyway. Grab a jacket, blanket, and some friends and head out somewhere decently far from all the lit-up buildings on campus. The goal is to see as many stars as possible, and the LED lights from freshman dorm windows won’t help.

If you’re serious about stargazing, you’re going to want to put away the phones once you’ve settled in to watch the night sky. Flashlights, Snapchat notifications, or any other bright screen will prevent your eyes from adjusting well to the dark. I’ve only seen the Milky Way once in my life, and you probably won’t be able to here, but it took over half an hour with no external sources of light for my eyes to begin to register it. The longer you sit in the dark, the more pinpricks of light will appear in the sky. Spoiler alert: there’s a lot to see up there.

We’ll start with my favorite constellation, Orion. Most widely known as the hunter from Greek mythology, Orion is recognizable in the night sky for its distinctive shape, particularly the three stars that make up his belt. If you’re in Princeton this time of year, face west to find the hunter in the sky (warning: if you’re on Poe Field after 11 p.m. or so, it’s probably set below Bloomberg, so maybe go somewhere where buildings don’t obstruct the horizon as much). If you can see Orion, you can use it as a launching pad for other constellations. By 10 p.m., you can just barely see Canis Major, his dog, above the horizon. Look for the bright star Sirius below and to the left of the hunter’s feet.

Rendering of Orion in the night sky.

Sierra Stern / The Daily Princetonian

Now we can find Mars. Picture Orion’s raised arms, holding a club and a shield. If you move up in roughly the direction his torso is pointing, you should come across the red planet.

This time of year, Mars is sitting in the constellation Taurus. Though I personally have trouble picturing it, this grouping of stars has been interpreted as a bull for thousands of years. It was called the “Bull of Heaven” in ancient Babylonia, and the Greeks and Egyptians saw the same animal. The Pleiades, a cluster of stars known commonly as the “Seven Sisters,” are located in Taurus’s bottom right corner.

I love the Pleiades because virtually every culture in the world has some association with it. The cluster is quite commonly depicted as sisters, such as by the Tachi people and the ancient Greeks, though they’re boys to the Iroquois and Cherokee.

Taurus, where the Pleiades can be found, is one of the 12 Western Zodiac constellations. Another Zodiac is to the upper left of Orion. Gemini, which in Greek mythology represents the twins Pollux and Castor, looks like two sideways stick figures holding hands. You might see more of a box shape at first; look for Castor’s feet right by Orion’s club.

Sadly, the constellations won’t appear as clearly as they do in the diagram; no promises that you’ll see the Gemini twins walking around campus at night. But you can definitely see Orion and Mars if it's early enough and if you know where to look.

Next, look for the Big Dipper. It should be to the northeast, pretty high in the sky. Fortunately, it’s quite recognizable. Seven bright stars form what looks like a ladle, with a bowl and handle. It’s a part of a larger constellation known as Ursa Major, which both the Greeks and many Native American tribes saw as a bear. Depending on who you ask, the handle of the Big Dipper could either form the bear’s tail or, as the Iroquois believe, hunters chasing the bear.

Take a moment now to find Merak and Dubhe on the Big Dipper, forming the right side of the bowl. If you draw a line connecting Merak to Dubhe and keep going, you’ll run into Polaris, known more commonly as the North Star. It marks the north celestial pole; all the other constellations seem to rotate around it while it remains nearly fixed in the sky.

Polaris was not always the North Star. Earth’s axis wobbles a little bit, a motion called precession, and so the star that aligns closest with the north celestial pole changes over thousands of years. This means that, to the ancient Egyptians, the North Star was Thuban, not Polaris.

Polaris is the tip of the Little Dipper’s handle. For some reason, I’ve had some trouble finding the Little Dipper here; stargazing can be hit or miss, but regardless of what you find, it’s always fun to sit on a blanket with friends and look up.

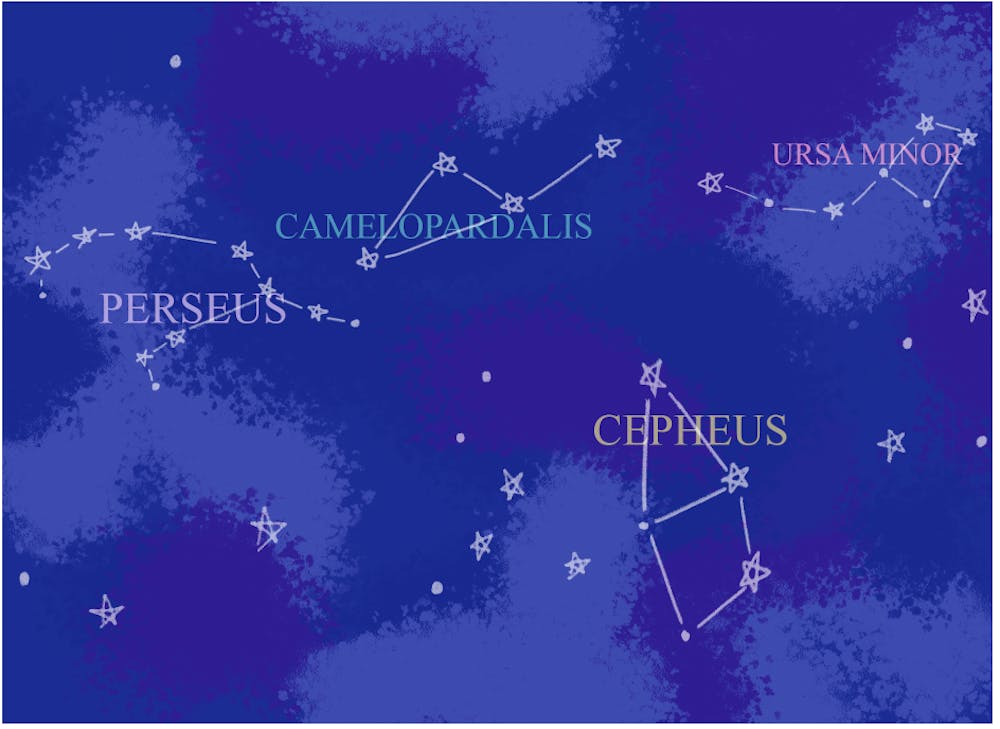

If you happen to see the Little Dipper, look below its handle, and you should see a group of stars that looks like a child’s drawing of a house. This is Cepheus, which leads us to a group of constellations all related to the Greek myth of Perseus.

Rendering of Cepheus, Perseus, Camelopardalis, and Ursa Minor in the night sky.

Sierra Stern / The Daily Princetonian

Cepheus is the king; to his left is his wife Cassiopeia, a zig-zag pattern that looks like a sideways ‘M.’ In Greek mythology, Cassiopeia’s vain bragging angered sea-nymphs, and Poseidon sent a sea monster to terrorize the kingdom as punishment. To appease the god, Cepheus and Cassiopeia were told to chain their daughter Andromeda to a rock in the ocean and sacrifice her to the beast; Poseidon, flying home on the winged horse Pegasus after killing Medusa, rescued and married her. Most of the characters in this story can be found in the same part of the sky. Though Andromeda has passed below the horizon by 10 p.m., to the left of Cassiopeia, you’ll find Perseus. Perseus is not quite as recognizable, in my opinion, so look closely at the shapes before heading out in order to recognize it.

Enjoy your stargazing!