For me, a fair part of the past year has been spent wondering what would signal a return to normalcy from the COVID-19 pandemic. Would it be the last patient taken off a ventilator and walking out of the ICU? Would it be a certain number of people vaccinated? Would it be the day all public health restrictions are lifted, and we can once again fill stadiums and theaters and bars without worry?

I am nowhere near the best-qualified person to answer such a question; I’m not an epidemiologist. But I can sense that we’re awfully close to a post-pandemic life. Sure, there’s hope in an accelerating vaccination effort, but that’s not all.

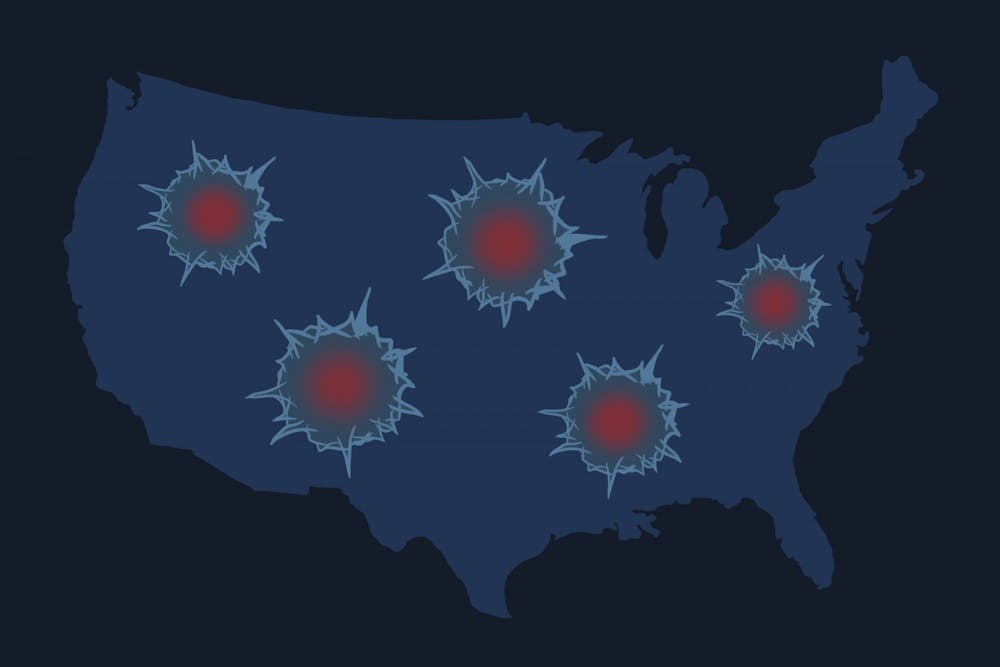

It has started to feel like America again — at least the America before COVID-19 — because mass shootings are back to dominating the headlines.

Not just one mass shooting; we live in plurals of these tragedies. Once more, my Twitter feed is a horrific mix of politicians condemning a previous shooting while reporters break news of a new one.

How tragic, how upside down, that a sign of normalcy in this country is periodical massacres. But the America I met as I’ve grown up is one riddled with bullet holes and broken families with loved ones taken away from them in an instant. There’s a profound sorrow in realizing one can tell a catastrophe like this historic pandemic is finally beginning to pass because the possibility of getting gunned down in a grocery store is beginning to take back the mental energy that, for the past year, had been dedicated to worrying about getting sick while grocery shopping. But like I said, this is the America I grew up in.

In fact, it’s very possible — maybe almost easy — to tell the story of my life with the normal markers of time replaced by one mass shooting or another. A chronology based on American carnage.

I was born less than a year after Columbine. I was a first grader when the Virginia Tech shooting occurred, and a handful of months later my dad received his first cancer diagnosis. Fourth grade, Fort Hood. I had to look these ones up to confirm their timing.

I was ten years old when Gabrielle Giffords was shot in Tucson. I was still in a bit of shock from Aurora, Colorado when my dad died of cancer two weeks after that shooting. And then the one that finally cracked something inside me was Sandy Hook — only four months of grieving my dad had passed by then.

That day is one of the clearest memories I have. It was almost 3 p.m., and the end of the school day approached, when every person in my K-12 Catholic school was ushered to the school gym for an unannounced assembly. As I sat on the basketball court’s wood floor, the principal told us that there was a tragic, confusing, difficult event being reported from another part of the country. He told us we had nothing to worry about, that we were safe, without telling us anything about what was actually happening. In fact, he asked the older students not to tell the younger students anything if we somehow saw the news so as not to scare them; let their parents handle it instead.

Then the assembly ended with a prayer from the parish priest. So I waited and waited until I could finally get to the school bus — beyond the school’s no phones policy — and read the news. There I was on a cold, green bus seat, staring at my phone, reading in horror. After that moment, I really began marking time with these unthinkable events.

Thirteen: the D.C. Navy Yard.

Fourteen: Fort Hood, again — the one I can actually remember.

Fifteen: Waco, Charleston, Colorado Springs, and San Bernardino.

Sixteen: Orlando’s Pulse nightclub.

Seventeen: Cincinnati (my hometown), Little Rock, Las Vegas, Sutherland Springs, Parkland.

Parkland was exactly one month before my 18th birthday and about two months before I came to Princeton Preview.

During Preview, I remember walking down Elm Drive from Alexander Beach to Whitman in the evening, close to dinner time. I met another pre-frosh during this walk. We introduced ourselves with all the typical questions.

While we were passing Dillon Gym, he told me he was from Florida. I mentioned the shooting. He told me that was his school. Even with all night to figure it out, I didn’t know what to say.

Later that year, my very last day of high school classes was interrupted by an active shooter drill.

Eighteen: Trenton, Cincinnati (again), Pittsburgh, Thousand Oaks, Aurora (Illinois).

I had arrived from OA exhausted and without any idea of what had happened outside of the base camp in West Virginia. I turned on my phone for the first time while walking through Blair Hall’s third floor only to receive a torrent of notifications about the Cincinnati shooting. It was the first big thing to happen after leaving home.

Nineteen: Virginia Beach, El Paso, Dayton, Midland-Odessa.

Twenty: D.C. (again) and Rochester.

Twenty-one: Atlanta and Boulder. (I’ve been 21 years old for less than two weeks.)

I often wonder if older generations even remotely understand what it’s like to grow up with time counted like this. To see jokes online about a pause in school shootings being an upside to virtual learning. To see back-to-back mass shootings in the headlines again and somehow think, it feels like America again.