This is the first article in a series examining the history of American partisanship. I write these articles because I firmly believe that historical precedent is key to developing ideas and solutions for contemporary problems. Princeton is replete with minds that will soon be tasked with leading the nation in this regard, and I wish to provide a handful of the nation’s future policymakers with the historical perspective that is fundamental to institutional development — though often neglected.

In times like the present, partisanship in American politics has been one of the sharpest thorns in the side of the nation. Tensions between the two parties have reached such heights as to generate an unprecedented insurrection in the seat of the federal government, followed by an equally unparalleled second impeachment of a President. Nevertheless, no matter how exceptional these circumstances seem to us today, it is certainly not the first time the United States has experienced rampant, elevated partisanship, and it probably will not be the last.

As seen in the words of Washington’s Farewell Address, we are surely not the first ones to worry about the dangers of party politics. This is not to diminish the importance of the events we recently experienced. On the contrary, I wish to provide — through historical precedent — reflections and lessons that we may apply in dealing with our present crisis of sectarianism. Through this series of histories of American partisanship, I want to show the many instances this Nation faced — and overcame — issues like the ones we face today.

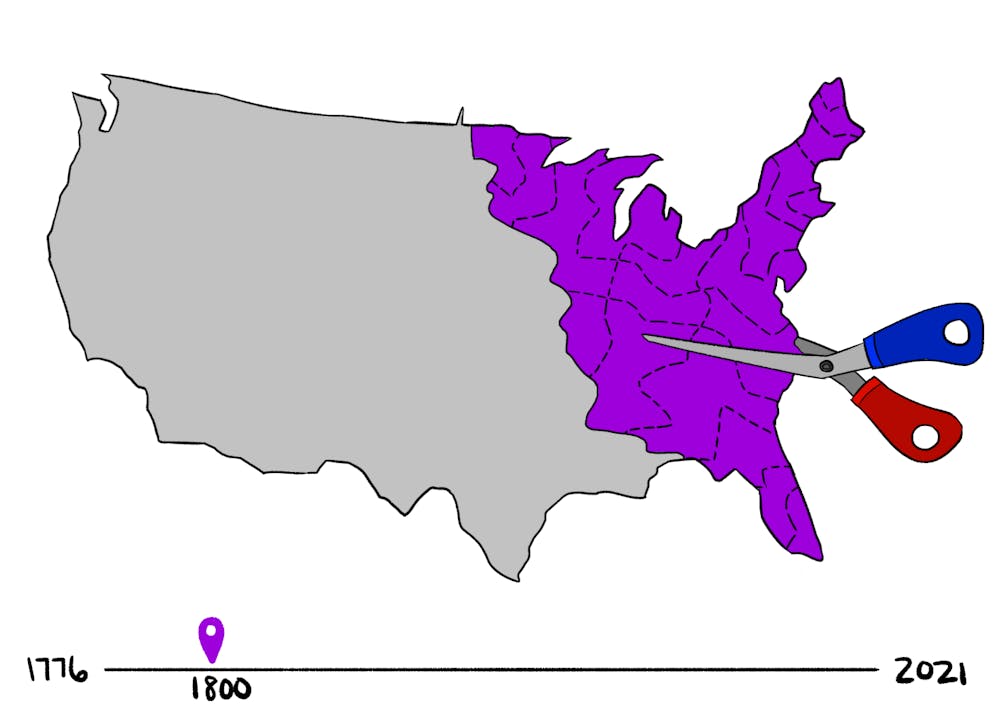

The history of American partisanship begins almost as soon as the Constitution’s ink first touched paper. However, party politics did not become a public affair until the end of Washington’s presidency, peaking with the Election of 1800, between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. As many may know from their knowledge of American history — and the election’s prominence within the hit-musical “Hamilton” — the Election of 1800 was controversial both in its rhetoric and its outcome: a stalemate that forced Congress to decide in favor of Jefferson. I would like to focus more on the former, as it was one of the first instances in American history where party lines were sharply drawn and political discourse turned sour.

Despite Washington’s warnings, the formation of political parties was inevitable, and the rhetoric escalated quickly. A political atmosphere that was characterized by consensus around the looming, monumental figure of Washington quickly turned to infighting after the general left office. This was the first instance in which printed media played a key role in campaigning, and the “attack ads” of the time soon turned heated.

Most famously, Thomas Jefferson had published in the papers a description of John Adams that deemed him “a blind, bald, crippled, toothless man [with] a hideous hermaphroditic character with neither the force and fitness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman.” In an era where the male political class prided itself on their masculine virtues of war and statesmanship, a more insulting remark could scarcely be conceived — and it was largely untrue. Adams was neither blind, disabled, nor toothless, though he was on his way to bald.

The American political sphere had not seen this kind of discourse before. But this escalation did not come from nowhere. It was, in effect, disguised by Washington’s efforts to project an apolitical image about himself and the members of his cabinet. These disagreements and animosities had always existed during Washington’s tenure.

However, Washington’s insistence to push them under the rug to give an appearance of consensus certainly did not allow the necessary debate that might have ended in compromise and some measure of reconciliation. As a result, any disagreement was either brushed aside or solved through frustrating, informal backroom dealings that did not provide the wider political sphere with the discussion they required.

When Washington left, and subsequently died, the lid was lifted off of Pandora's box, and members of his cabinet, once friends and allies during the Revolution, turned into bitter enemies.

In the end, after the election tied and had to be decided by the House, Jefferson won. President Adams, much like President Trump, refused to attend Jefferson’s inauguration. Jefferson and Adams remained enemies for 13 years after, until they eventually reconciled via a prolific period of correspondence.

The most valuable lesson from these events — apart from the knowledge that American partisanship is as old as the country — is that consensus does not mean the in-existence of factions. Political parties, while causing division and generating instances of unsavory speech, are necessary as instruments of consensus-making. No one is “above politics.” In many ways, a purely nonpartisan approach to politics stifles the innovation that arises when ideas are met with counterpoints that then generate discussion, compromise, and reconciliation.

Under the present situation of this country, several agents from both sides of the aisle have proposed “bipartisanship” as the panacea for the division facing the Nation. However, this version of bipartisanship seems to be rooted in inaction and the preservation of the status quo, while portraying these efforts as successes merely because they had votes from the other side.

Suppressing partisan discourse will not mitigate the toxic aspects of factionalism. We must acknowledge that in any important issue, different sides will arise. In acknowledging the inevitability of partisanship, we can re-examine how different sides of an argument do not act as impenetrable fortresses that refuse to give, but as two (or more) voices in a dialogue seeking consensus. When the end of partisanship is to reach consensus, politics will not be dominated by “cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men,” as Washington worried. Instead, it will allow the ideas that better pass strict yet sincere scrutiny to prevail. The spheres of government will be dominated by constructive ideas instead of scheming politicians.

While the immediate rhetorical effects of the Election of 1800 may have appeared destabilizing at the time, it allowed the country to make peace with its own partisanship. Subsequent electoral rhetoric was not as inflammatory. Jefferson even found himself able to reach important, public compromises with his political adversaries. While sudden, the Election of 1800 opened the eyes of the American political sphere. It revealed that — contrary to the assertions of the mighty Washington — partisanship was necessary, and it could even be a useful tool for representative democracy.

Juan José López Haddad is a junior concentrating in history from Caracas, Venezuela. He can be reached at jhaddad@princeton.edu.