Giving Europe a nuclear force is an idea dating back seven decades. A lack of public support and limited interest, beyond France’s government and defense industry, means it will likely remain just an idea.

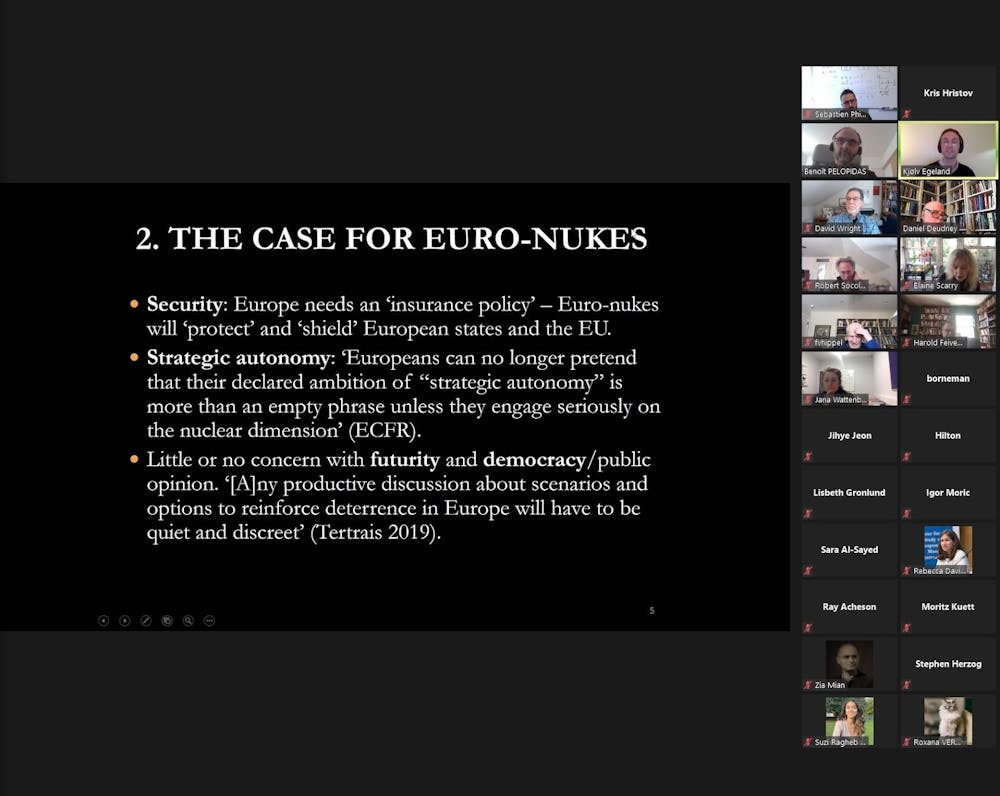

At a Wednesday lecture, Kjølv Egeland and Benoît Pelopidas discussed the idea of a consolidation of European nuclear weapons, an idea commonly referred to as the “Euro-nuke.” Egeland and Pelopidas published a research article in August 2020, arguing against the “Euro-nuke.”

Euro-nukes date back to the 1950s, before France even had its own nuclear weapon. (France would detonate its first bomb, Gerboise Bleue, in 1960.) The idea centers around a consolidation of European nuclear weapons, controlled by an entity within Europe for the purpose of European security.

Egeland and Pelopidas termed the Euro-nuke as a “zombie idea,” unlikely to ever be adopted, but resurrected every few years in the media. During the 1950s, France went as far as to consider offering Italy and Germany access to prospective French nuclear weapons. This idea was scrapped by Charles de Gaulle, but later resurrected by him during the 1960s as a counter to a similar American proposal.

In the 1990s, the topic of Euro-nukes re-emerged as Europe consolidated further by the Maastricht Treaty (which formed the EU) and a common currency was adopted. In 2008, French President Nicolas Sarkozy considered nuclear weapons as a key element of French national security, which his successor François Hollande affirmed in 2012. With the recent exit of the United Kingdom from the European Union, France remains the only Nuclear Weapons State (NWS) within the EU.

Supporters of European nuclear weapons are not in agreement over how far joint control should go. Moderates support European nuclear coordination independent of the United States. More radical proponents propose a European nuclear arsenal entirely controlled by Brussels.

Egeland and Pelopidas criticized the notion that European nuclear weapons were effective in addressing problems currently facing the EU.

“The 2016 EU global strategy document outlines threats to the European Union. Economic volatility, terrorism, and climate change are not addressed by nuclear weapons,” Egeland said.

Additionally, Pelopidas and Egeland identified the lack of public support for nuclear weapons. A survey they conducted showed that more than 80 percent of a European sample believed that nuclear weapons should not be used in any case. Egeland further noted that 15 percent of survey respondents believed that nuclear weapons should be used when there is an existential threat to a country, and 3.2 percent believed they should be used if an ally is attacked.

Within Europe, it was pointed out that even Poland, a country whose relationship with Russia would predispose it to support a stronger European defense, was the third most in favor of disarmament.

So why does the idea consistently re-emerge in France?

“Advocacy for Euro-nukes comes from the French nuclear defense industry or French Government,” Egeland explained.

Much of the supposed broad support comes from like-minded think tanks. Pelopidas noted that conservative American think tanks which wish to reduce government spending also support the idea of European nuclear weapons.

Beyond its own borders, France’s nuclear arsenal also lacks a NATO commitment. The United Kingdom and the United States both coordinate their nuclear strategy within the NATO framework. According to Egeland and Pelopidas, this means that any challenge to British nuclear arms in Parliament can be immediately dismissed due to a commitment to an international organization. The weapons cannot be immoral if others are relying on the United Kingdom to have them.

Finally, there is also a simpler explanation behind France’s attitude towards Euro-nukes.

“France wants other nations to help pay for its defense. This makes the Euro-nukes convenient,” Pelopidas said.

Host Sébastien Philippe added that the “institutionalization of nuclear weapons in France looks like a religion from the outside.”

Egeland and Pelopidas concluded their panel with a call to action from parliamentarians and citizens, whose voices were “completely ignored from the onset of nuclear weapons development.”

In the meantime, France has recently launched a program to replace its current generation of Le Triomphant class nuclear missile submarines starting in 2035. The new submarine class is set to be in service until 2090.

Egeland is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellow and Lecturer in International Security at the Center for International Studies at Sciences Po in Paris, affiliated with the Nuclear Knowledges program. He is also a Research Fellow at the Norwegian Academy of International Law.

Pelopidas is the founding director of the Nuclear Knowledges program at the Center for International Studies at Sciences Po, Paris and has been a visiting fellow at the University’s Program on Science and Global Security.

The panel was moderated by Sébastien Philippe, a researcher with the School of Public and International Affairs Program on Science and Global Security.

The lecture, titled “European nuclear weapons — again?”, was sponsored by the Program on Science and Global Security and co-sponsored by the Program in Contemporary European Politics and Society. The event was held virtually on Feb. 24.