Last week, the United States crossed a tragic and entirely preventable milestone: 500,000 COVID-19 deaths. I want to challenge everyone — and especially my fellow classmates and faculty at the School of Public and International Affairs (SPIA) — to be more precise with our language when we talk about this.

Contrary to President Biden’s recent proclamation, half a million Americans were not simply “lost” to COVID-19. They may have died fighting a coronavirus infection, but their deaths were actively — and needlessly — caused by deceitful and recklessly irresponsible government leaders, Big Business profiteers, and our society’s existing set of oppressive structures. These 500,000+ souls deserve justice.

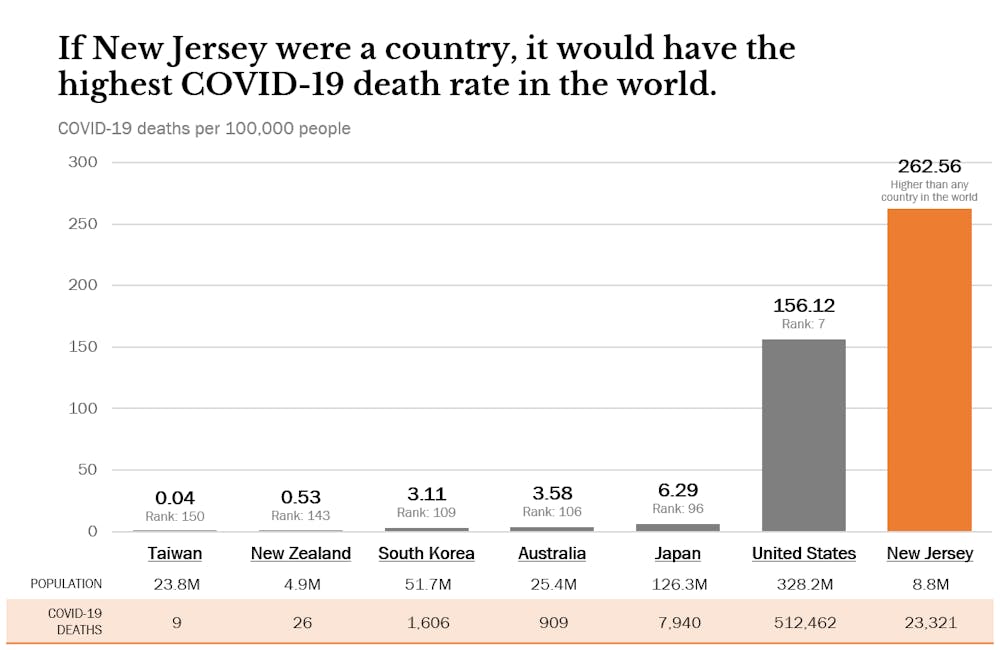

In New Jersey, a state with only 8.8 million residents, more than 23,000 of our neighbors have perished. That is more than double the number of COVID-19 deaths seen in Japan, South Korea, Australia, Taiwan, and New Zealand combined, despite these five countries containing over 230 million people. Approximately one in every 11 New Jerseyians has tested positive for the virus, itself an undercount due to early barriers to testing, many of which remain even today.

Data source: Statista estimates of John Hopkins University, World Bank, and Insee data, retrieved Mar. 2, 2021. New Jersey also has the highest death rate among all U.S. states. Note: Statista excludes microstates from its rankings.

Of course, it might be a stretch to expect that our government can successfully prevent 100 percent of all deaths related to COVID-19. Despite implementing a slew of scientifically-driven measures, Taiwan has still seen nine deaths due to COVID-19. Australia, a similarly populous country that took action at a slightly slower pace, has sadly reported over 900 deaths. However, these are losses several magnitudes smaller than in most U.S. states.

Despite some implicitly racist suggestions, it’s not that citizens of these countries were simply more “obedient” or readily willing to accept quarantine restrictions. Instead, COVID-19’s international success stories have been largely attributed to effective public policies, including forward-thinking systems and structures put in place long before January 2020. Looking at these countries where citizens are safe and life is largely back to normal, it is starkly apparent that the vast majority of Americans who have died of COVID-19 were unnecessary victims.

In light of this harsh reality, I’ve felt dismayed that the courses I’ve taken at SPIA in the past year have rarely interrogated the underlying forces that have made our nation so vulnerable to mass tragedy, especially compared to other societies around the world.

When we fail to name the actors and policies that cause harm, we risk repeating the same mistakes and suffering.

It can be all too easy to singularly blame former President Trump for his colossal abdication of responsibility. But Trump didn’t act alone: he was egged on by countless civic society leaders, including GOP governors who refused to impose mask orders and corporate lobbyists who blocked relief for low-income Americans. To understand their murderous conduct, we have to look deeper at our country’s pre-existing conditions, including those that existed long before Donald Trump entered the White House.

For starters, it’s useful to observe how our news media has covered COVID-19’s racial disparities. Last July, The New York Times published “The Fullest Look Yet at the Racial Inequity of Coronavirus,” an article reaffirming earlier predictions that BIPOC Americans would disproportionately suffer in the midst of a health crisis.

Though the Times piece vaguely points to “systemic racism,” its analysis only delves one layer deep. Consider this excerpt: “Experts point to circumstances that have made Black and Latino people more likely than white people to be exposed to the virus: Many of them have front-line jobs that keep them from working at home; rely on public transportation; or live in cramped apartments or multigenerational homes.”

While these statements are factually true, they’re presented with no mention of the perpetrators and policies that engineered these conditions. After all, it's not by random chance that BIPOC Americans are more likely than their white peers to experience labor exploitation and/or lack the material resources to afford adequate housing or a private vehicle.

Instead, these realities are the cumulative result of a dizzying array of longstanding public and private policies, including enslavement, land theft, immigration exclusion, redlining, union busting, mass incarceration, voter suppression, gerrymandering, and more.

When we fail to name these harmful policies (and the elite class of white men who wrote and continue to enact them), we can all too easily perpetuate "damage imagery," a phenomenon where groups that have been marginalized are portrayed as inherently damaged, pathological, or simply victims of “bad luck.”

Although conservatives frequently weaponize damage imagery to justify overtly racist policies, its use is no less pervasive in left-leaning spaces. You might recognize it in programs that attest to “uplift” so-called “at-risk” communities, with staff who conduct their activities without acknowledging why current inequities exist. When we omit or obfuscate the underlying context, we can inadvertently reinforce racist stereotypes or harmful tropes — and miss the opportunity to collectively address the root causes of suffering.

To avoid this pitfall, the Center for the Study of Social Policy challenges us to lead with acknowledgment of historical and systemic barriers while also centering the “strengths and solutions” within communities who have been impacted.

At a first glance, it sounds pretty straightforward. After all, how can we solve a problem if we don't know who or what caused it in the first place?

Unfortunately, that’s why it’s all the more baffling when policymakers and economists downplay or omit historical conditions from their analyses — or worse, refuse to acknowledge their very existence.

Last year, as a student advocate for SPIA’s newly implemented Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) requirement, I debated with senior faculty members who argued that DEI frameworks and curricula would “only be useful to a small subset of students.” I’ve taken courses with multiple instructors who, despite their widely acclaimed expertise, still struggle to say the word “racism” out loud when discussing American domestic policy.

To be clear, I don’t expect my professors or colleagues to be experts on every way in which racism or other forms of oppression pervade our societal systems. But I do expect them to acknowledge and wish to uncover their existence, especially as we collectively grasp for solutions for positive change.

Stepping back to COVID-19, I’m interested in naming harms and unapologetically advancing policies to avoid the same mass tragedy in the future.

After all, how can we emerge from a national health crisis without acknowledging how Medicaid’s existing state-by-state structure was designed to allow Southern white leaders to deny access to low-income Black people, a reality that persists to this day? How do we move forward from 500,000 deaths under an unsustainable health care system — the only system among OECD nations that doesn’t guarantee access to all citizens and one in which providers and private insurers profit billions while charging prices multiple times higher than in other countries?

Even if we prioritize eliminating inequities, whether or not we name their root causes can fundamentally change the analyses we make and the policies we write. It’s the difference between fighting for positive improvements and righting a wrong. Without orienting ourselves to the latter, we often end up walking in circles, completely missing the elephant in the room.

After 9/11, we didn’t say Americans were killed by plane crashes or collapsing buildings. After Sandy Hook, Pulse, and Parkland, we didn’t say children, teenagers, and young LGBTQ+ people died of bullet wounds, as if their injuries magically appeared. We name the killers and their intent because it is important to acknowledge harm, hold those responsible accountable, and offer justice to victims and survivors.

To my fellow Princetonians and Americans, I want us all to be more proactive in naming how we got to half a million deaths and counting. It didn’t have to happen this way. Moving forward requires full-throated, unabashed truth.

Mark Lee (he/him) is a Master of Public Affairs candidate at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs from Irvine, Calif. He can be reached at markml@princeton.edu.