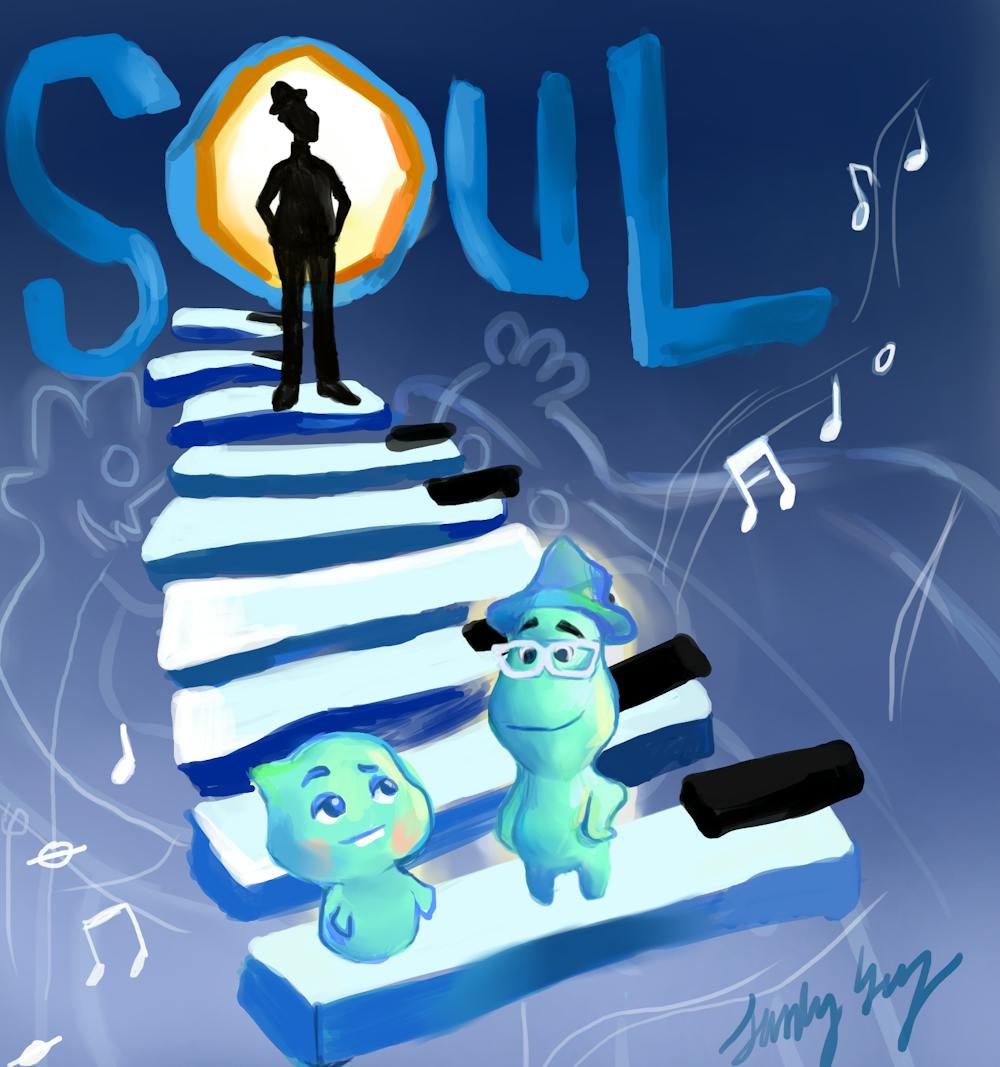

“Soul” is the latest movie from Disney’s Pixar, released on Disney+ on December 25 of last year. The film tells the story of Joe Gardner (voiced by Jamie Foxx), a 45-year-old middle-school music teacher in New York who has lived his whole life chasing his dream of becoming a successful jazz performer. Just when he’s finally given the musical break he’s worked his whole life for, he unexpectedly “dies.” His soul is then transported out of his body. This becomes the catalyst for him to rediscover a way back into his body and pursue his artistic dreams. But while Joe’s soul is out of his body, he goes on a fantastical journey that helps him to discover the meaning of life.

Given the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on our lives, “Soul” came at a timely moment.

As Associate Prospect Editor José Pablo Fernández Garcia ’23 so accurately told me, “I really think ‘Soul’ speaks to the weird reality of the past year, during which the question always seemed to be: how to keep life going? This year has been recognizing that ‘pausing life’ is just as valid a form of life.”

For me, a senior in college trying to figure out what to do post-graduation, this movie hit especially hard.

This past year, I came to the “late” realization that I have been spending my four years of college moving toward a field I actually don’t want to pursue. Ironically, 2020 had been a frantic attempt to reset and race toward my newly discovered “purpose” and passion for storytelling and becoming an animation director.

However, instead of feeling happy that I’d found or chosen a particular path, I became anxious about getting “there,” thinking constantly about how to reach this goal of success that I’d so narrowly defined for myself. I would scour websites for hours looking for internships, then become discouraged by the fact that I had none of the skills or experiences top animation firms were looking for. I even reached out to many alumni working at Pixar, who helped me tremendously with their advice and knowledge of the industry. I talked about my dream to work at Pixar for hours with my parents and it seemed like everyday, all I could think about was how and when could I get “there.”

My friends, parents, and mentors were great supporters, encouraging and pushing me forward while also reminding me that the journey is often “not linear” — even people in their 50s are still discovering what their “purpose” is. But I was negating everyone's help by fretting and obsessing over my passion for storytelling to the point that I, like Joe at the beginning of “Soul,” couldn’t or wouldn’t think about anything else.

“Soul” was what ultimately tossed a bucket of water on my head and pulled me out from the weeds. I saw myself in both protagonist Joe Gardner and deuteragonist 22. 22 is a soul who has refused to go to Earth for millennia, partly because she didn’t believe she was good enough for Earth. Joe is tasked with mentoring 22. I realized, like 22, that I was letting negative voices in my head tell me I was a good-at-nothing-nobody. And like Joe, I was letting my self-absorbed goals blind me from my surroundings, the needs of others, and the rest of what life had to offer.

What also inspired me as much as the movie itself was its co-director Kemp Powers, Pixar’s first African American co-director and screenwriter. His arrival to Pixar came from a combination of trauma, luck, trial-and-error, health scares, reflection, and seizing chance opportunities. It took him a whole lifetime to build up his career and to collect the number of life experiences to inspire the characters and story of “Soul.”

In 1988, when he was 14 and hanging out with a few friends, Powers toyed with a gun belonging to his mother, Evelyn, who was at work at that time. The gun went off and accidentally killed his then 14-year-old best friend. Luckily, “the friend’s family did not press charges and forgave Powers, who was sentenced to a year of counseling,” according to an article from The Washington Post.

That traumatic event, however, sparked his desire to write a 2004 memoir called “The Shooting.” Telling the story gave Powers a chance to say everything he needed to say about it. And afterward, Powers knew that he, much like Joe Gardner, had to continue living his life. Even in moments of despair, he couldn’t let that be the “defining event” of his life.

Like Powers, “Soul” reminds us that there is still hope and purpose in living, even when we feel like we ruined it. We must not let our one thing define us.

I relate to this, as someone who has also been plagued with trauma and mental health for almost 10 years. In eighth grade, I suffered from an eating disorder, one that almost killed me (and caused lasting damage to my family’s relationships). I used to fear that my mental health history and biological dispositions would prevent me from achieving my highest potential. I didn’t want my eating disorder to define me, but I could see it seeping into my relationships with others and myself.

Like Powers, writing gave me a place to release that, to process the emotions and trauma, and to address them for what they are. There is still much I have yet to tell about my story. It took me some time to even start writing about it. But once I felt ready to lay my past out onto a blank piece of paper, I could feel myself healing and ready to move on.

For storytelling to be powerful, the story must be lived.

The magic of storytelling is that, by telling a very specific story, many people can still relate to it and feel its messages speak to them.

Only a few talented storytellers can deliver such a film. Kemp Powers is one of those people, and his addition to the team brought so much authenticity to “Soul.”

Fortunately, Powers also had teachers who saw his raw writing talent and encouraged him to keep going with it. While in college at Howard University, Powers took an essay test that his instructor, Heather Banks, found extremely advanced. She later confided in him, saying he was “a ringer — a professional.”

Powers recalls her saying that she’d “never had a freshman come in and write this way.”

“I was like: ‘Well, I’ll be damned, I’m good at something,’ at a time when I really didn’t know if I was.”

However, Powers’s writing prowess did not take him directly to screenwriting. Unlike other directors at Pixar, who started as animators, storyboard artists, or occasionally long-time screenwriters, Powers’s career started off — and stayed for a long time — in journalism.

After he graduated college, Powers entered a long editor and reporter career in a variety of outlets such as Reuters, Forbes, and Yahoo. He jumped around out of necessity as it was hard for him to stay in this journalism business.

However, he still continued writing on the side. On nights and weekends, he wrote fiction, and one of his works, the play “One Night in Miami,” received critical acclaim after it premiered in Los Angeles in 2013.

Powers was pursuing his passion on the side of his real job, just like Joe Gardner in “Soul” was.

What caused the biggest shift for him from journalism to Hollywood was entirely unpredictable. In 2015, Powers developed a serious muscle-tissue syndrome called rhabdomyolysis from an allergic reaction to Tamiflu. While on his Baltimore hospital bed, he contemplated the journalism industry he had toiled in for two decades. Feeling like his ideas were not as valued and his creativity constricted, he decided that if he recovered from his disease, he’d quit his job as a contract editor at AOL and move into entertainment.

Health situations, especially death or near-death ones, can make people rethink how they’ve been living their lives. This happened to Powers, as it did in “Soul” to Joe and even Joe’s go-to barber, Dez. Joe previously had thought Dez was magnificent at his craft and therefore must have been “born to be a barber.” But Joe’s view changes when Dez confesses that it was his daughter’s health issues that pivoted his dreams from being a vet (and paying for an expensive medical school) to becoming a barber.

That didn’t mean Dez wasn’t happy with his situation, though. He seized his opportunity and mastered his craft. He found beauty in his job, in the connections he made with his clients, and the ability to hear their stories. And because of that, it became meaningful to him.

“Soul” beautifully illustrates not only the close relationship people have with their hair stylists but also the reality that we aren’t “born to be something.” That our work doesn’t have to be our purpose. Our work can still be meaningful even if it wasn’t what we initially sought out to do.

The movie didn’t entirely pull the Pixar dream out from underneath me. But it did make me realize that there are many paths to doing what you love. Powers’ serendipitous path from journalism to directing and screenwriting, or Dez’s unexpected swerve into hairstyling, are testaments to that.

Rather than focusing on what the ultimate “goals” I want to achieve are, this movie taught me to ask myself “why” and “how”: why did I want this goal? What does achieving it really give me?

I had believed for too long that I was constantly falling behind others, that it was too late to pursue this animation dream of mine, which was so opposite from what I’d been doing most of my life. “Soul” showed me the beauty (and necessity) of patience — slowing down in life and appreciating what you have around you. When non-ideal situations happen, how can I adapt and keep finding joy in what I can do, not what I can’t do?

Powers’s story showed me that I don’t have to be doing things since I was born to be good at them. Nor do I have to enter my dream field right out of college or be a specialist by my 20s. Life is about the long game. I couldn’t tether my happiness and my feelings of accomplishment to some future, momentary goal of becoming a director at Pixar.

Because, once I get there, wherever “there” is, the feeling of pride and achievement will only last a few seconds. And then, well, what’s next? What else did I have to live for besides my work? How do I continue finding fulfillment?

A part of me wishes “Soul” came out earlier in 2020 because it might have shaped my pandemic life and mindset significantly. But I also do believe it was only by going through my experiences of blind desire, passionate pursuit, and hopelessness that I could resonate with and understand it so well.