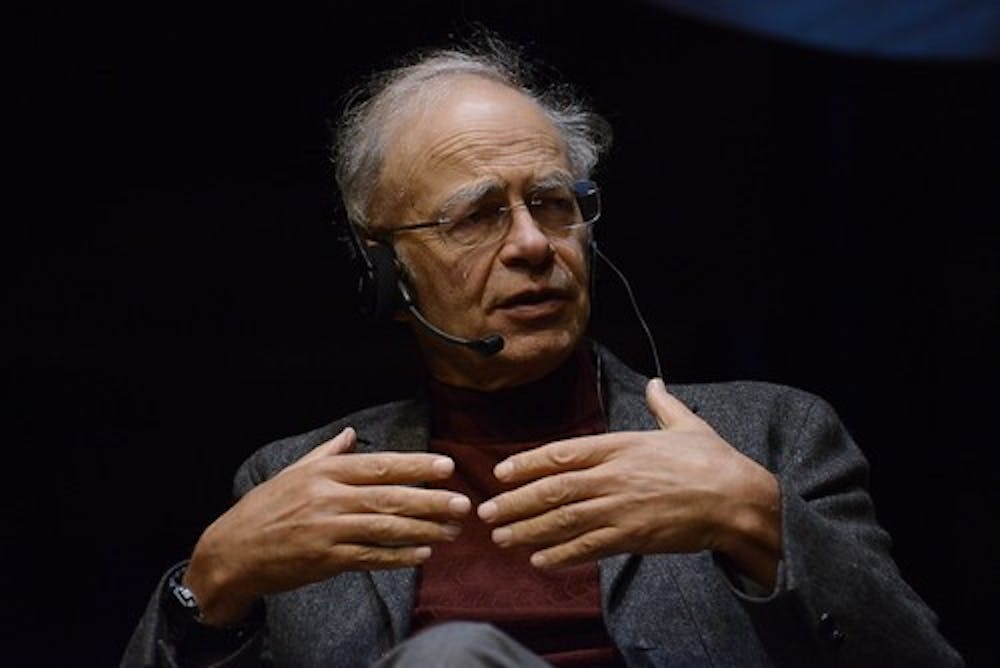

It’s been 50 years since Peter Singer, Professor of Bioethics at Princeton University’s Center for Human Values, wrote his essay “Famine, Affluence, and Morality,” arguing that the affluent ought to be donating more of their wealth to humanitarian causes.

The essay, written in 1971 and published the next year in the academic journal Philosophy and Public Affairs, stresses the moral obligation to help those in need if one can do so without causing more harm; that is, Singer argues that if an individual could donate to starving refugees without significantly damaging their own livelihood or the well-being of others, they should — not just out of charity but out of moral obligation.

“Famine, Affluence, and Morality” confronts the reader with their own complacency regarding global suffering, and the passage of time has not led to a heartening perspective. Half a century later, the world is in the midst of a refugee crisis, wars and famines continue to afflict millions, and society is still rife with poverty and inequality. A modern frame of reference provides a new understanding of what may be necessary to goad the world into action, but we’ll start by reexamining Singer’s reasoning regarding the affluents’ duty to help those in need.

Singer’s famous drowning child example displays his logic on the matter: If any of us were to walk by a pond in which a child was drowning, we “ought to wade in and pull the child out.” Our shoes might get muddy, but the cost of a new pair would be far outweighed by the life of the child in front of us.

In such a situation, we would feel morally obliged to save that child’s life. While the child’s mother might thank us for wading into the pool and pulling the child out of the water, it seems more an act of duty than of charity. Anyone who walked by and did nothing, letting the child drown, would be despised as a morally evil person.

Singer contends that we should feel just as duty-bound to save the life of a child living in poverty thousands of miles away as we do to save the life of the child in the pool. He notes in his essay that “the fact that a person is physically near to us, so that we have personal contact with him, may make it more likely that we shall assist him, but this does not show that we ought to help him rather than another who happens to be further away.”

What is striking about Singer’s essay is not that he writes in favor of charity, as encouraging both individuals and governments to give money to the hungry and displaced isn’t typically controversial if done correctly — that is, without leading to dependent economies in post-colonial countries or the pushing of cultural and political beliefs onto other societies, which has often been paired with a continued military presence. Focusing on non-problematic charity organizations and practices, Singer’s essay stands out not because of his support for the causes but because of his argument that humanitarian aid donations are affluent people’s duty rather than praiseworthy examples of generosity.

Singer holds that we should stop treating donations from the affluent as acts of charity and instead treat them as moral obligations. The philosopher advocates a shift in society’s understanding of them, writing that “the traditional distinction between duty and charity cannot be drawn, or at least, not in the place we normally draw it.”

However, 50 years after the writing of Singer’s influential essay, that line between altruism and obligation remains firmly planted.

Though charitable giving from individuals continues to grow and organizational and government work has greatly reduced global poverty, inequality is still stark. Also stark is the way in which the affluent in society go about their days ignoring the suffering of others, wearing clothes sewn by child laborers in far-off countries and remaining generally inactive regarding others’ lack of medicine or food.

The United Nations estimates that, in 2015, 10 percent of the world’s total population was living in extreme poverty. While that percentage continued to decline through 2019, reaching 8.2 percent, the rate of extreme poverty was forecasted to increase the next year due to the effects of the pandemic, with an estimated increase of 71 million people living in extreme poverty because of COVID-19.

Despite the vast inequality that exists both within developed countries and between nations, expectations for sharing one’s wealth or surplus with those in need have not changed much. Consider how much praise MacKenzie Scott ’92, the ex-wife of Jeff Bezos ’86, received for donating over $4 billion to charities this past year. She received roughly $38 billion worth of Amazon shares from the divorce, now worth over $60 billion.

Of course, it’s not just billionaires who could and, as Singer argues, should give more. This isn’t meant as a guilt trip but rather as simply a fact. Many of us, the author of this piece included, could be giving more to people in need. So why don’t we?

In his essay, Singer writes that “what it is possible for a man to do and what he is likely to do are both, I think, very greatly influenced by what people around him are doing and expecting him to do.” When we praise billionaires for giving away a fraction of their surplus money, perhaps we are signaling that it is not an expectation that they do so. Rather than feeling duty-bound to donate most of their absurd wealth, they feel praised and charitable for donating scraps of it. The same could, perhaps, be said for anyone with a surplus of funds or assets they don’t necessarily need to live comfortably, not just billionaires.

Reading Singer’s essay half a century later, in a world that is still unable to address the suffering, hunger, and displacement of many of its inhabitants, I couldn’t help but wonder what I’d attach as a footnote. I grappled most with his diagnosis of the cause of apathy amongst the affluent. Singer highlights societal expectations and locational proximity as factors that seem to influence peoples’ habits when it comes to helping others. If I had his essay in print, I’d probably scribble in the margins my personal assessment that there is an overlooked reason why the rich don’t help the poor: a gradual desensitization to the chronic issue of global poverty.

I’m sure that physical or cultural distance and the perception of aid as charity rather than duty do affect the giving habits of those in developed countries, leading the affluent to ignore far-off plights. If a famine erupted in New York City or London, likely many more Western pockets would open charitably than to a similarly scaled famine in China; I can’t deny that people tend to be more generous towards those closer in proximity to them as well as tthose to whom they perceive themselves to be closer in relation, perhaps because of a shared language or culture.

However, I also believe that this influx in generosity would be a result of humanity’s hardwiring to notice change over consistency; people are more likely to notice the wealthy Upper East side fallen on hard times rather than the continuation of hard times somewhere else. Yes, an individual’s cultural or locational proximity to the region in question would influence their reaction to such a plight, but perhaps even more important in dictating their sense of urgency is whether they see it as a perpetuation of a chronic issue or a shift from the usual.

Consider the ongoing issue of homelessness and poverty in American cities. Though this is a local issue to those who live in the United States, it is also long-term, and the longer you live in a city, the easier it is to pass by someone asking for money without stopping. Just like someone living next to a waterfall will gradually learn to ignore the background sound of rushing water, we’ve learned to ignore certain crises; that is, we’ve allowed ongoing poverty and hunger in far-off lands to become background noise.

We need to reexamine what ought to be expected of the affluent to help the less privileged, but we also need to recalibrate our perspective of what is an allowable or normal level of suffering in the world.

We won’t solve global poverty simply by confronting the affluent with heart-wrenching pictures of barefoot children digging through garbage piles or raising awareness and pushing the issue to the front of people’s minds. While this might be useful in collecting some donations, what would ultimately help most is a rewiring of those minds, a shifting in society’s perception about what’s acceptable in the world, and an effort by the media to make the status quo of global poverty abnormal.

Of course, society doesn’t necessarily change when someone publishes an essay pointing out its inherent immoralities. If politicians listened to philosophers, we’d probably be living in a very different world — and who knows whether it would be better?

However, when individuals read essays like Singer’s and truly reflect on how they should be living, society gradually begins to change. Shifting our sense of what’s “normal,” as well as heeding Singer’s call to reconsider what we call charity and duty, will help steer the world towards more urgent action for the tackling of global issues — most importantly, the issues of continued human suffering that Singer’s essay pointed to five decades ago.