The following is a guest contribution and reflects the author’s views alone. For information on how to submit an article to the Opinion section, click here.

Every morning, I peer out my dorm window to admire a swath of the ancestral and current homeland of the Lenni Lenape people. Even though a valley of snow lies atop most grasses and bushels, the trees stand tall and elegant — reminders that as the land grows, we do, too. I am grateful to be here. To every person who has made my stay possible, from those who deliver food to others who coordinate COVID-19 testing, I thank you. However, I would be remiss not to call attention to the ways in which my presence on campus, and that of my peers, is adversely impacting the natural environment.

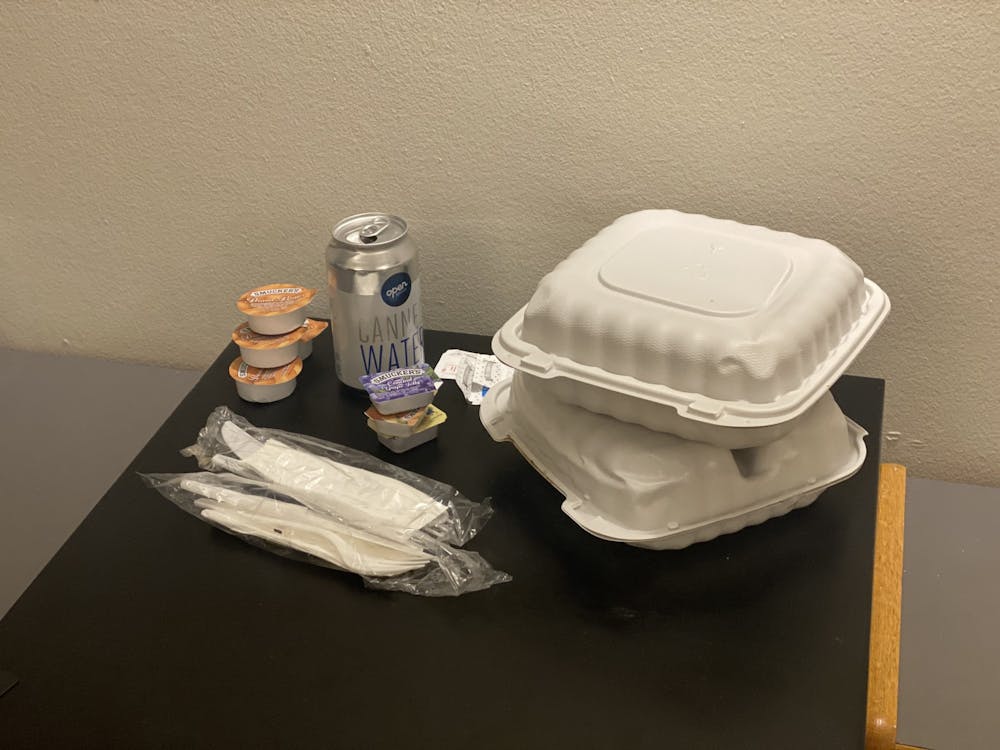

Since my arrival, I have discarded 50 plastic film sleeves, 32 variations of single-use dishes, 13 plastic clamshells, and five condiment containers to total at least 104 pieces of garbage. Not to mention the 35 or so water cans I have tossed in the recycling bin, which, by the appearance of the stained and slightly moldy interior of the blue receptacle in my nearest trash room, likely functions as a supplementary trash container.

Considering these observations, imagine how much waste those of us on campus have created since the start of the semester. If every residing undergraduate student produced as much waste as the average American per day, our collective trash between Feb. 1 and Feb. 13 would amount to 183,902 pounds. As Kelsey Ji highlighted in November, much of this waste can be attributed to food and related packaging, items that I would not have used in such abundance had I remained at home.

Leading the global production of municipal solid waste (MSW), the United States is home to four percent of the world’s human population yet generates triple that percentage in garbage, most of which ends up in landfills, incineration plants, bodies of water, or nations with limited environmental regulations. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, food, paper products, and plastics constitute 57 percent of all annually generated garbage. The organization recommends a reduced consumption approach to waste management, but most citizens of wealthier nations tend to opt for a practice that soothes our conscience while preserving our spending habits: recycling.

Recycling has become too much of a hassle to execute successfully in the United States and abroad. Despite substantial campaigning efforts, most people do not recycle correctly and end up throwing anything from candy wrappers to hangers into the characteristic triangle-marked bins. Even when we do recycle, the majority of the material gets loaded into a dumpster anyway. Since China banned the import of MSW in 2018, the market for recyclable plastics and paper materials has drastically declined while the amount of waste has accumulated.

Consequently, the United States has fewer options for disposing our annual 292 million-ton sack of refuse. Waste management services around the nation have forced cities to an ultimatum: incinerate items with the trash or pay much higher rates to recycle them. You can imagine what many officials decide. Furthermore, you may think: “Well, incineration facilities practice energy recovery, right?” Yes, but not sustainably. The process of burning trash has been found to diffuse toxins such as carbon monoxide, dioxins, lead, and mercury into the atmosphere. Alternatively, organic waste in landfills releases methane as it decomposes while chemicals from inorganic material seep into soils and groundwater. The unpleasant landscape and odor are additional deterrents to expanding the landfill industry. Take, for example, Big Sky Environmental, a dumping ground in West Jefferson, Ala. where 48 states convoy their MSW and sewage. The cup you just tossed in the trash will soon be on its way to a destination you do not want to visit.

At the University, the plastic utensils we use have a decomposition period of at least a thousand years, though the material never really decomposes — it just fractures into granular pieces. Even the production of compostable materials and plant-based plastics, such as those that constitute the Pactiv EarthChoice containers made available in our dining halls, often require more energy and resources than its compostability advantages could offset.

Therefore, the best solution to our campus waste problem, considering safety regulations, is to reduce the number of items we toss in either the recycling or trash bin. The Office of Sustainability could offer students sponges and metal utensils while Housing Services adds dish soap in every kitchen. On our part, let us not grab more than we will eat. Leftovers and snacks are great, and I hope everyone is able to eat well; however, snagging a salad only to let it shrivel in a corner of your refrigerator should be avoided.

More broadly, I ask you, community members and readers of the ‘Prince’ wherever you are, to actively and effectively reduce our collective waste. If you have the privilege to choose what you consume, consider adopting a simple phrase: refuse, reduce, reuse, recycle. Follow the phrase in this order to resist the marketing designed to make you crave more, buy more, and ignore the consequences of your purchases. Remember that recycling is no longer, and never really was, the redeeming quality of our cultural overconsumption.

Personal efforts to reduce waste are indeed beneficial, but we need structural transformations if we want to protect our planet. I urge the University to meet its own standards and obligations as one of the world’s leading institutions of higher education. Although demands for the University to fulfill its “service to humanity” grow louder every month, petitions and referendums, even those that garner substantial communal support such as Divest Princeton and the Princeton Campaign for Prison Divestment, continue to be largely ignored by the administration.

Hence, let us try a different approach. We are the individuals for whom the University purchases thousands of single-use containers and utensils that are eventually shuttled offsite. Thus, our conscious consumerism can prompt the University to adjust its spending patterns and infrastructure to become a reduced zero-waste campus. Environmental impact is not an issue solely within the purview of the Office of Sustainability; rather, it is a challenge against a global economy driven by convenience, consumption, and profitability at the expense of ecological and human health. With intention, institutions — academic and otherwise — can operate a circular economy that embraces regenerative ecosystems and environmental justice. But even as we envision a better future, our present behaviors beset the world. We must immediately attend to the pollution crisis, not in the rhetorical tomorrow but now.

Chioma Ugwonali is a first-year from Arlington, Texas. She can be reached at ugwonali@princeton.edu.