The following is a guest contribution and reflects the author’s views alone. For information on how to submit an article to the Opinion section, click here.

In the midst of a global pandemic in which Princeton students are barely even allowed to be on campus and life is rife with cancellations, one of the most divisive and exclusive practices at Princeton continues. Last fall, while reminiscing with some fellow Princeton alums over Zoom, I was enraged to discover that during some of the most confusing, uncomfortable, and isolating times that many students have faced, the Princeton eating clubs are still conducting Bicker. I was absolutely floored that someone thought it was a good idea to hold Bicker this year. Though, to be perfectly honest, I cannot really believe how anyone thinks it is a good idea to hold Bicker at all.

For context, I am a recent University graduate and was a member of Cannon Dial Elm. I regretfully admit I exploited the twisted system to get in and propagated it from the inside, too. As an athlete, I schemed with my teammates, made deals with other teams, gave perfectly nice people horrifically low scores, and basically did whatever it took to get more of my teammates accepted into the club. I played the game, and I am not proud of it. In fact, I am deeply ashamed of what I did.

After experiencing Bicker from both sides, I have only become more infuriated with the audacity of the process. For a university and a student body that champions “inclusion” so fiercely (and rightly so), it is laughably hypocritical to allow Bicker to continue. I have witnessed that Bicker outcomes have nothing to do with the character of the prospective members, but rather on arbitrary factors such as connections in the club and the order in which they are discussed. Furthermore, this process brings out the worst in everyone, creating unnecessary drama and hurt that can linger far past Bicker season. Because of this, during my last spring Bicker, I decided to take detailed notes (from which I quote directly in the following paragraphs) with the hope of exposing the process. In this article, I share my findings and offer an alternative to Bicker.

How the Process Works

For those who are not familiar, Bicker is basically when students rush to get into eating clubs. Eating clubs comprise the social scene at Princeton and, despite all their faults, are a great way to be a part of a community on campus. At Cannon, “bickerees” (prospective members) spend two nights playing icebreaker games and two nights having one-on-one conversations with the Cannon members so both groups can get to know each other. Throughout this process, members log on to the Bicker website and add red or green cards to each bickeree’s profile, giving negative or positive comments, respectively, on their experiences interacting with the bickerees. Then, the bickerees wait while the members select who to accept behind closed doors.

During the first step in the selection process at Cannon, each member gives all the bickerees an initial score. The top 25 scores from this process are “turbo’ed” — they automatically get accepted into the club. Next, the long nights of discussions begin. For two nights in a row, for four to six hours each, the rest of the bickerees’ pictures are projected onto a screen in the Cannon dining hall and each bickeree is individually assessed by members based on previous interactions or experiences at Bicker games and conversations.

Bickerees may also have a “Crane Card” or a “Last Word” where a close friend speaks on their behalf for about thirty seconds, vying for the other members to let them into the club. On average, each bickeree is discussed for about 1-2 minutes, after which each member of the club gives them a score. Once all the bickerees are discussed, scores are summed and the top 80 or so bickerees get in, and the rest get “hosed” — or rejected from the club. This process varies by club, but there are commonalities — namely, the Bicker games and the discussions (though length, content, and scoring systems vary).

From the outside, Bicker may seem benign — the club can only hold so many people, so some are inevitably filtered out. But beneath the surface, Bicker is a method to propagate exclusivity by ranking your classmates. Bicker is just another way of deciding who is cool enough to eat with you at lunch.

Findings:

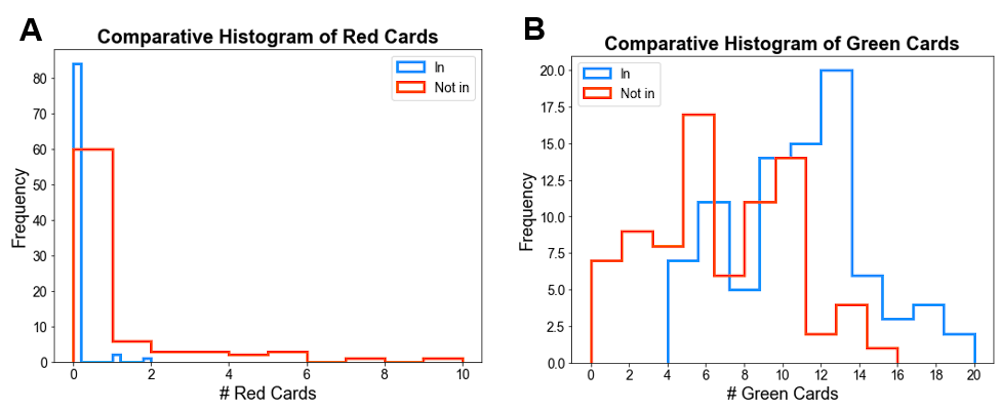

Figure 1: Histograms of the distribution of red cards (A) or green cards (B) between the population of bickerees that got in (blue) or did not get in (orange). In (A), those who did not get in had a statistically significantly higher average number of red cards (0.77) than those who got in (0.39, p=0.00014). In other words, most bickerees that got in (blue) had zero red cards as indicated by the spike at 0, whereas many bickerees that did not get in (orange) had one or more red cards as indicated by the more right-skewed data. Conversely, in (B), the histogram of green cards for bickerees that got in (blue) is shifted towards much higher values (to the right on the graph) as compared to the histogram for bickerees that did not get in (orange). This shows that those who did not get in had a statistically significantly lower average of green cards (6.6) than those who got in (10.8, p=5.2E-12).

Though most comments at discussions are positive, there is also a non-negligible amount of bad-mouthing. Worse yet, even the mildest of negative comments — for example, “I just got bad vibes” or “[I] didn’t have great interactions with her,” could ruin your chances to get into the club. At my last spring Bicker, there were an average of just 0.39 red cards per bickeree. Even more telling, the average red cards for those that got hosed was 0.77, and the average for those who got in was 0.05, showing a statistically significant difference between the two groups (Figure 1A, one-tailed t-test, p=0.00014). From this, it is evident that just one red card (which could mean just one bad interaction with one member) could be the difference between getting into and getting hosed from the club.

What makes this process even more hurtful is that bickerees have no idea what is said about them during discussions, which often means they assume the worst. If a bickeree did not get into a club, it is likely that they will think people in the club disliked them, when the reality is that someone may have just given them a red card because the bickeree was the “least engaging conversation [they] had.”

Green cards are also a huge determinant of who gets accepted. The average number of green cards for the people that got hosed was 6.6, and the average for those that got in was 10.8 (Figure 1B, one-tailed t-test, p = 5.2E-12). Without context, this result is innocent: if someone has more positive interactions with the members, they are more likely to get in. Knowing the intricate nature of bicker, however, reveals the more sinister correlation — more prior connections will get you more green cards, even if you did not interact with the person at all during bicker. I have witnessed first hand that members of athletic teams will form “alliances” with other teams; in other words, “I’ll give your teammates a green card if you give some to ours.” As an athlete, I have personally added green cards to profiles of bickerees I had never met just because we had formed an “alliance” with their team.

It also helps immensely if you have a very close friend in the club (for example, a teammate) to give you a Crane Card or Last Word. A much greater number of people who got accepted had Crane Cards and/or Last Words (one-tailed t-test, p = 2.3E-11, p = 2.7E-06, respectively). This further proves that someone who has close connections in the club has a much higher likelihood of getting in than someone who does not.

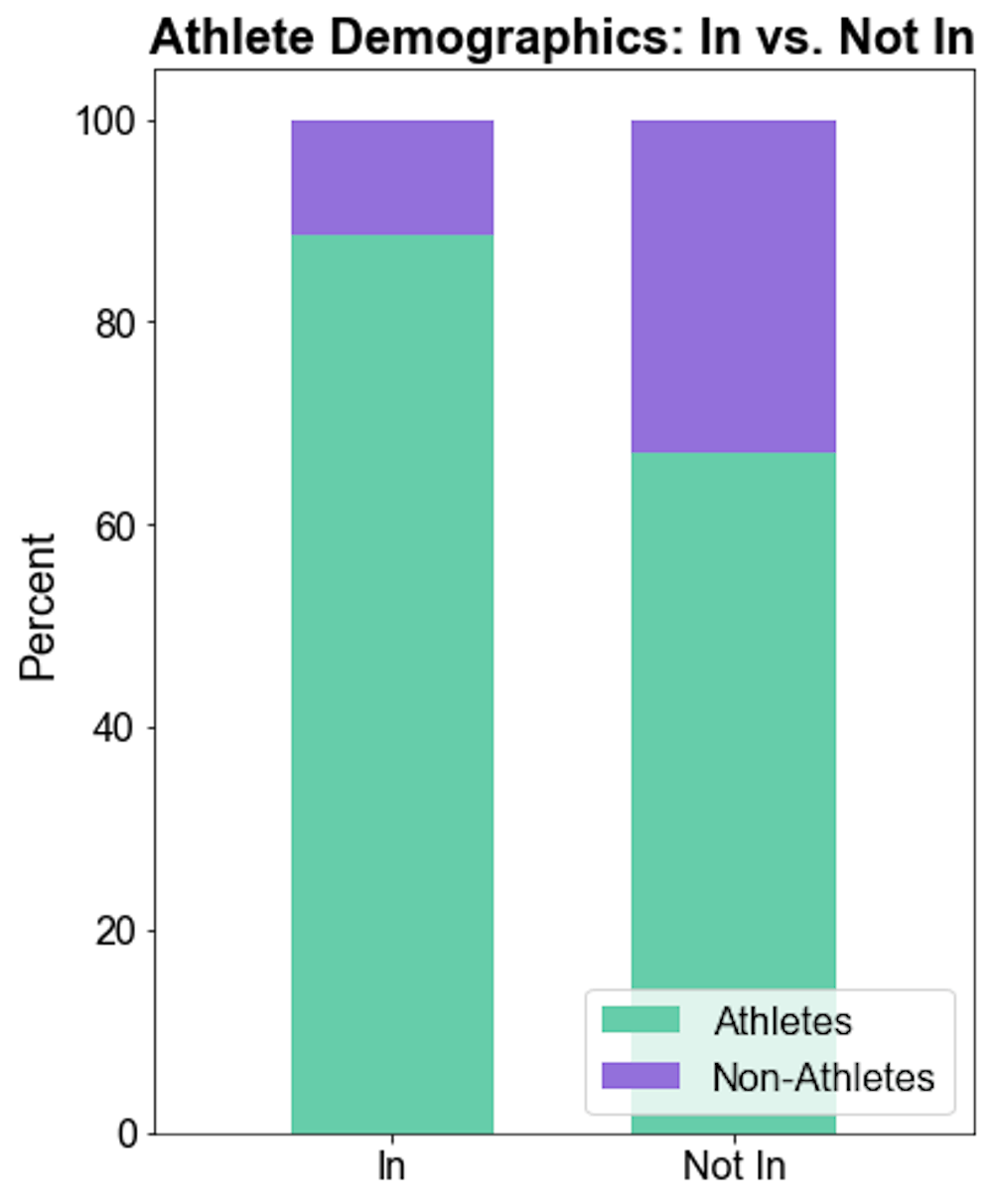

Though athletic teams are not the only way people could have connections in the club (for example, other extracurriculars, majors, co-workers), athletic rosters serve as a useful proxy to clearly determine previous connections. At the time that this spring Bicker data was taken, 72 percent of Cannon was part of a varsity athletic team, compared to only 18 percent in the general student body at Princeton. Being part of an athletic team as a bickeree at Cannon, therefore, practically guarantees that you know at least one other person in the club well (and up to 29 other people if you were on the football team). In fact, the ratio of athletes to non-athletes in those that got accepted compared to those that did not was statistically significantly higher (Figure 2, one-tailed t-test, p = 0.00037), with 89 percent of people that got accepted being athletes, and only 67 percent of those that did not get in being athletes.

Figure 2: Comparison of the percentages of athletes (green) and non-athletes (purple) in the population of bickerees that got in versus those that did not. Percentages are as follows: In = 88.5% athletes, 11.5% non-athletes; Not in = 67.1% athletes, 32.9% non-athletes.

From this, it is clear that being an athlete gives Cannon bickerees a major advantage. Though this bias is likely due in part to the fact that Cannon will attract teammates of those who are already in the club, it inherently limits the scope of the community and goes directly against the ideals of “diversity and inclusion.” In addition, it creates a vicious cycle: if there are more athletes in the club, more athletes will get into the club, which burns people just because of limited connections.

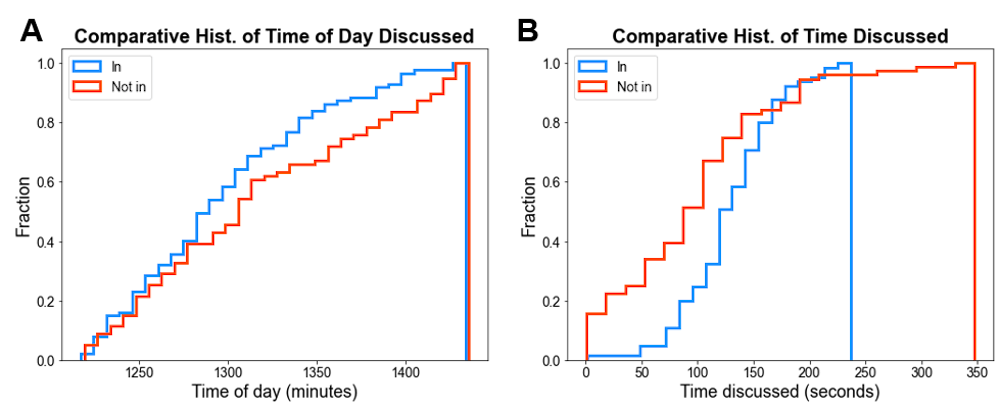

Exploiting connections is not even the worst part. There are several uncontrollable, but important, factors that were statistically significantly different between the bickerees that got in and those that did not. For example, the bickerees that got in were, on average, discussed at an earlier time in the evening than those that did not (Figure 3A, one-tailed t-test, p = 0.024). This statistic and personal observation suggest that admission rates go down because people get much more tired and cranky as the long nights of discussions go on. Unbeknownst to the bickerees, the order in which they are discussed was determined completely by when they signed up for Bicker on the website. In addition, when excluding those that were turbo’ed from the analysis, people who got in were often discussed for a statistically significantly longer amount of time than those who did not (Figure 3B, one-tailed t-test, p = 0.0014).

Figure 3: Comparative histograms of the time of day discussed (A) and amount of time discussed (B) between populations of bickerees who got in (blue) versus those who did not. In (A), one can see that the blue (in) and orange (not in) histograms begin to diverge around ~1280, indicating that more people who got in had already been discussed by this point; in other words, a higher percentage of people that were discussed later did not get in. In (B), the orange histogram (not in) is above the blue histogram (in) at the left side of the graph, showing that a larger percentage of those that did not get in were discussed for a much shorter amount of time. Histograms are cumulative, meaning that the value associated with each bin indicates all values that are less than or equal to that bin. Histograms are also normalized (for ease of comparison), meaning that each bin represents a fraction out of 1.0 (rather than a raw frequency).

Another glaring flaw in this process is that while discussing bickerees, club members view the person’s submitted profile picture to put a name to a face. One potential consequence of this practice is discrimination based on perceived attractiveness and other physical characteristics over which bickerees have no control. Such concern is validated by the fact that numerous articles have indicated biases based on appearance, for example, racial or attractiveness discrimination in hiring. Something as archaic as rejecting people based on unconscious biases cannot continue in good conscience.

In summary: if you want to get into Cannon, make sure you know a lot of people in the club that will give you green cards, make sure you are not “too nervous to talk” or “seem pretty out of it” as to avoid getting get a red card, make sure you are an athlete, sign up early to get discussed earlier, and upload a high-quality picture to your Bicker profile. It is telling that this list does not include attributes like “be a good person” or “be a trustworthy friend.” Getting into Cannon — and, admittedly, most eating clubs — is just a big, exclusive game.

Many people have countered my objections to Bicker with the claim that “we want to have the best club on the street” or “Bicker accepts the people that deserve to be in the club” — but that is complete and utter absurdity. Students should be able to sit down and enjoy a meal with anyone on Princeton’s campus. And if you do not want to, then you have the choice to sit at another table. Bicker does not accomplish the goal of “making the best club on the street.” It only encourages slimy social climbing and exploiting connections. Worse yet, it rationalizes exclusion, and it is incredibly hurtful to those that get rejected. It brings out the most scathing and discriminatory side of people, only to hurt those around them. And for what?

A Proposal for Change

Though there is no perfect solution, I have thought a lot about ways to improve Bicker. The unfortunate truth is that eating clubs do have limited capacities. There are some clubs that rely on an inclusive model of allowing people to join until they reach capacity. An additional option would be to do all the same Bicker games, conversations, and discussions, but instead of relying solely on scores to determine those who get in, a weighted lottery system could be used where people with higher scores have a higher chance of getting in. This would not mitigate all the negative aspects of Bicker, but it takes away some of the pain caused by outright rejection and replaces it with feelings of bad luck instead.

I would, however, hope that this proposal is just one step in ridding eating clubs of Bicker entirely. The fairest way to do so is by instituting a lottery system weighted only by class year instead. This would ensure that people who do not get in the first time they Bicker will get in the second time around. The lottery system would save busy students time by completely eliminating the Bicker process (in total, at least a 20-hour process in one horrific week) and would both give bickerees without connections a fairer chance of getting in as well as decrease the pain caused to those who are hosed. It is one thing to get rejected by your peers, and completely another to get rejected by a random number generator.

I know this study is limited in scope and is subject to biases, so I hope that this serves only as a stepping stone for future exploration into this questionable process. For those of you who are a product of the Bicker system like I was, I hope you are just as outraged and uncomfortable with it as I am. I further hope you voice this outrage and question the process more deeply so that we can effect change. For those of you who have nothing to do with Bicker, I hope you can also voice your dissent to pressure those involved to change. Despite its innocent facade, Bicker is an unacceptable scheme and should not continue. It is a process founded on exclusivity and propagated by those so obsessed with tradition they become oblivious to their own hypocrisy. Such an antiquated, isolating, and hurtful system tarnishes the Princeton name for as long as it is allowed to continue.

Methods

In total, there were 166 bickerees and 87 of those got in; 25 people were turbo’d and three of those people decided to join another club, so they were counted as “not in.”

For all one-tailed t-tests, bickerees that got in and bickerees that did not get in were split into two groups, and the means of the values between these groups were compared using the T-test: Two-Sample Assuming Equal Variances from the Analysis ToolPak in Excel. Anything that was indicated as “statistically significant” used an alpha value of 0.05 (in other words, the p-values were less than 0.05; all raw p-values are included in their respective analyses). In the indicated analysis (amount of time discussed), those that were turbo’d were eliminated from the analysis.

For the analyses where the value was either a “yes” or a “no” (ex. athlete status, crane card, last word), those that were a “yes” received a value of one, and those that were a “no” received a value of zero. T-tests were then carried out in the method described above.

Editor’s Note: The author of this column was granted anonymity due to the sensitive details described and the potential for retaliation. The data used comes from notes taken by the author during the Bicker process provided to the ‘Prince’ in a redacted form. The ‘Prince’ was unable to independently verify the integrity of the data but did verify the accuracy of the statistical analyses presented in the article based on that data, as well as the author’s identity as a former member of the club.