In the documentary “HyperNormalisation,” Adam Curtis explains that cyberspace, as it was initially conceived, promised an alternate world free from the politics and corruption of the “real world.” This digital realm, its idealist advocates believed, presented an opportunity to build a democratic utopia accessible anywhere by anyone — it would be a sacred and protected space separate from reality.

Yet, in contemporary society, it is impossible to divorce the digital from the real. Through our use of digital platforms and technologies, the virtual undergirds every moment of the quotidian, creating a cognitive dissonance in our experience of the “real world.” What is real, and what is just a simulation? What differentiates humans from artificial intelligence? How has our very ontology begun to change as a result of the blurring between real and virtual worlds?

These are a few of the many questions the multimedia artist, filmmaker, and musician Lawrence Lek explores in his practice. Lek is currently a Ph.D. candidate in machine learning at the Royal College of Art in London, England, and is of Malaysian-Chinese descent. He received his B.A. in architecture from the Trinity College at the University of Cambridge, and his Masters in architecture from The Cooper Union in New York. Lek has been awarded several residencies and has been exhibited widely, from Rome to Hong Kong. He is represented by Sadie Coles HQ, an art gallery in London.

Through a constellation of works generated across various platforms and mediums, Lek builds parallel worlds of his own to reimagine the present in the future (or the future in the present). On Nov. 5, Lek gave a public talk hosted by the Princeton Art Museum to discuss the research interests and questions that guide his practice, focusing in particular on three films: “Sinofuturism (1839-2046 AD)” (2016), “Geomancer” (2017), and “AIDOL” (2019). Lek is the 2020 Sarah Lee Elson International Artist-In-Residence, a residency sponsored by the Museum in which an artist working outside the United States visits the University campus to present a public lecture and hold workshops, discussions, and meetings with students and faculty.

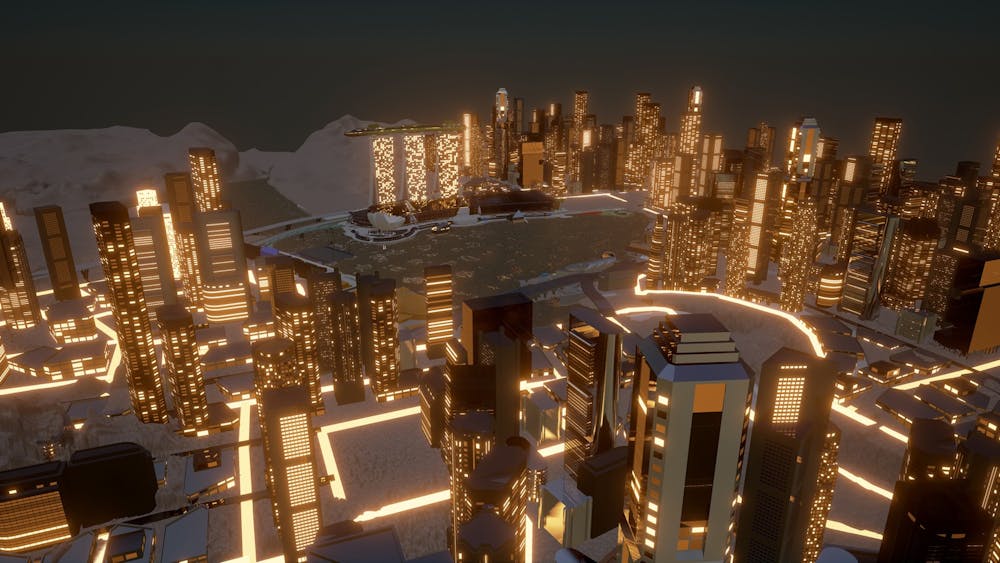

Perhaps influenced by his background in architecture, Lek is fascinated by worldbuilding. He remakes familiar cityscapes digitally as a means of exploring how time bends in the virtual world. In “Geomancer,” Lek manipulates time on multiple fronts: On the one hand, he warps narrative time by making an AI satellite the protagonist in a bildungsroman (coming of age) story set during the centennial of Singapore’s independence, superimposing the timeline of the AI onto that of the nation-state.

On the other hand, Lek alters the physical landscape — the visual elements of worldbuilding — to signal the fluidity of geological and historical time. In the film, the contemporary cityscape of Singapore’s Marina Bay grounds the film in the present, while environmental details denote the futurity of the film, such as flooding induced by climate change. Place becomes a way to bring divergent moments together into a singular point in time, obfuscating the distinction between present and future, real and virtual.

Lawrence Lek, Geomancer, 2017 [still] HD video, stereo sound / © Lawrence Lek, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

Lek also interrogates the real-digital divide by incorporating AI into his work. Citing game theorist Alan Turing GS ’38, he suggests that “intelligence is not a definite thing … it’s not a destination to arrive to, but it’s a state where you actually don’t know the difference between A or B … it’s this idea of uncertainty … and it’s also the way a lot of machine learning and deep-learning algorithms operate today.”

In his talk, Lek mentioned a historic match of the Chinese board game Go, in which Google DeepMind’s AlphaGo AI defeated a human Go master for the first time. Human genius, Lek seems to imply, is not so far removed from the machine — a suggestive claim he explores in his work, such as in the film “AIDOL,” in which an AI songwriter helps a fading pop star revitalize her career.

Lek most directly probes at the overlap between human intelligence and AI in his video essay, “Sinofuturism (1839-2046 AD).” A blend of documentary, social realism, and conspiracy, the film puts forth a theory of ontology modeled on several stereotypes about China, which Lek calls Sinofuturism, defined in the video essay as “a form of artificial intelligence, a massively distributed neural network focused on copying rather than originality, addicted to learning of massive amounts of raw data rather than philosophical critique or morality, with a posthuman capacity for work, and an unprecedented sense of collective will to power.”

Lek first conceived of the work while researching the relationship between East Asia and AI and the media’s representations of the two. He observed that “portrayals of Chinese industrialization and of AI were actually mirror images of each other — [that through rapid expansion and growth, they would] either … save us all or destroy us all.”

In “Sinofuturism,” Lek highlights similarities between the two through seven overarching themes — computing, copying, gaming, studying, addiction, labor, and gambling — claiming in the film that the “essential unknowability of the AI to the human, of the mystique of a consciousness beyond emotional understanding, is exactly the same other identified in Orientalism.”

His self-evident awareness of the narrative convergence between AI and Chinese industrialism transforms his embrace of their stereotypes into an act of subversion, one that articulates a broader truth about human civilization — namely, as Lek puts it, that cultures simply want to perpetuate themselves.

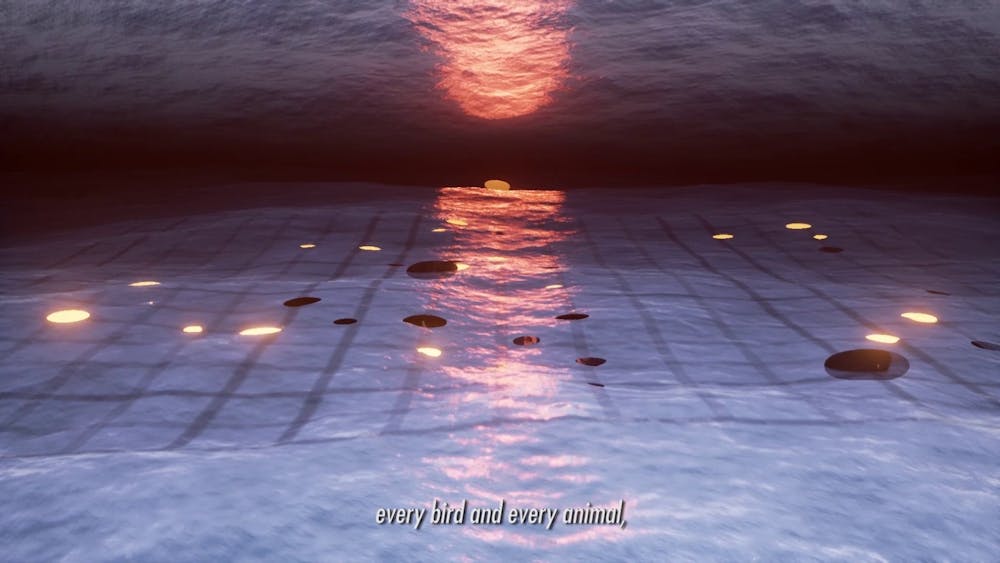

Lawrence Lek, Geomancer, 2017 [still] HD video, stereo sound / © Lawrence Lek, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

Most of the film consists of found footage — a melange of newsreels, InfoWars clips, gaming tournaments, movie stills, and virtual reality simulations — which document the fiction of China put forth by the media. By appropriating the original source material and thus creating a copy, Lek presents his theory of Sinofuturism through the very form of the work.

The copy — the virtual, the counterfeit, the non-human — becomes synonymous with the real, as it is only through this act of copying that the video essay and Lek’s theory of Sinofuturism come into being.

As an assemblage of internet footage, the (im)materiality of “Sinofuturism” challenges traditional hierarchies within the art world, blurring the distinction between “high art” and “low art” — that is, the “autonomous artwork” of genius and the art of the masses (pop culture). Through “Sinofuturism,” Lek asks us to reassess our valuation of the copy: “[the] video essay [‘Sinofuturism’] … [aims] to see things from the machine’s perspective, to see copying as not lesser than originality … to see gameplay and gambling as not lesser than the fine arts or humanities or sciences as well. To configure not just the right and wrong relationship through bias, but also to reconfigure the role of art, broadly speaking, in transforming reality.”

Lek thus challenges the singularity and authenticity of the original (the human) and elevates the position of the copy (the inhuman AI, the Chinese worker). The copy is distributed, consumed and reprocessed to produce new contents; much like the original, it molds reality.

All works of art, regardless of whether they are copies or “originals,” are only legible insofar as they recycle a language familiar to their audience. What is a work of art, then, but a re-presentation of signs already in circulation?