Upon matriculating at Princeton, I received two things in the mail: the classic black Princeton t-shirt and a copy of the pre-read, “Speak Freely.” I wasn’t the only one: the entire student body was encouraged to read the book. That’s how seriously the University takes freedom of speech — at least on the surface.

Nassau Hall urges students and faculty to ‘speak freely’ both in and out of the classroom. Over the summer, we saw Vice President for Campus Life Rochelle Calhoun and President Christopher Eisgruber ’83 defend students and staff’s freedom to use racial slurs. Last month, President Eisgruber reaffirmed that stance.

Time and again, University officials have defended the right to free speech on Princeton’s campus. Even so, free speech isn’t equal at Princeton, especially when it comes to issues deemed political or controversial.

For months now, I have worked on Divest Princeton’s campaign for fossil fuel divestment. As I have spoken with University employees, some staff have expressed support for the movement, but declined to publicly endorse our campaign, for fear of their position and reputation. I began to wonder: how can the University promote free expression when staff members feel unable to speak out?

Since some members of the University community indicated they could not speak freely, I hoped to use my platform to share their stories. And so, with the support of the Princeton Environmental Activism Coalition (of which I am a member), I surveyed staff on their perception of free speech at the University. We reached out to 190 staff, administrators, and research associates from 18 different offices, centers, and residential colleges, ranging from the High Meadows Environmental Institute to the Office of Diversity and Inclusion and the Pace Center for Civic Engagement.

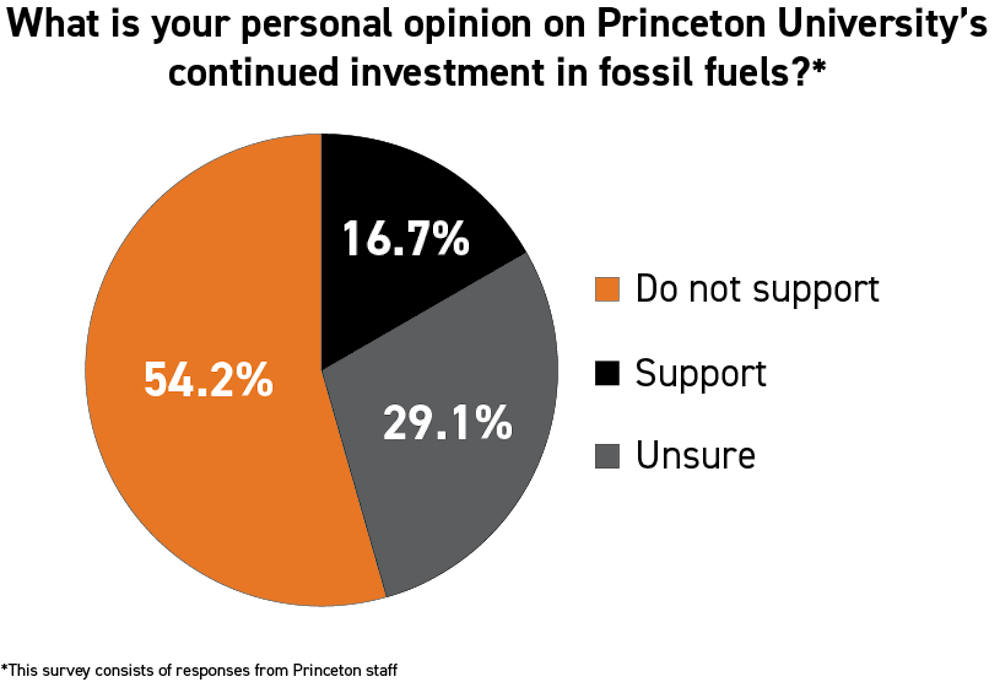

Our survey was anonymous and asked for opinions on fossil fuel divestment and climate change, as well as whether the respondent had experienced free-speech constraints at the University. Most yes-no questions included a free-response option. We hoped to reach as representative a sample as possible, while preserving anonymity.

In total, 24 staff members, administrators, and researchers responded to our survey, of which 58.3 percent expressed support for Princeton’s divestment from fossil fuels and 20.8 percent expressed opposition. The remaining 20.9 percent expressed ambivalence or reported needing more information to decide.

Abby Nishiwaki / The Daily Princetonian

Most importantly, many of the respondents expressed being unable to freely and openly express their personal views on divestment, despite their vested interest in sustainability and climate change. Just 27.3 percent of staff members responded “Yes” to the question, “If you do not support the University’s investment in fossil fuels, do you feel as though you have the ability to voice your opposition freely with members of the Princeton community, including other administrators, faculty, and students?”

One respondent reported having “received messaging from the Princeton administration, directly or indirectly, that [their] position or reputation would be threatened should [they] speak on the divestment as a topic in a way that does not reflect the University stance.”

Furthermore, one respondent wrote, “as a staff member in charge of communications, [they were] not supposed to express support for the divestment movement.” Another suggested, “staff do not have the same academic freedoms that faculty do.”

Admittedly, our survey possessed significant limitations. Of the thousands of employees who work at the University, we contacted only a small percentage. Within that group, fewer than 13 percent submitted the survey. Staff members with favorable views towards divestment might have been more likely to respond. Nonetheless, even just one employee who feels uncomfortable speaking out is cause for concern.

Conversations with University spokespeople made clear to me that no official University policy prevents staff from personally speaking out about divestment. I was assured that all community members’ free speech is highly valued, regardless of their position. That understanding, however, is evidently not shared among all staff.

After completing the survey, one staff member reached out to elaborate on what they understood to be the consequences of supporting divestment. They were only comfortable messaging me privately, due to concerns about their position if they commented publicly. According to that employee, “If a staff member wants to publicly speak out or take a stance for divestment at Princeton, then you are disagreeing with Princeton’s stance, so really the choice there is to quit and work somewhere else where your values align or be fired if you take your objections too far.”

While no official policies may restrict staff’s free expression, the lack of clarity over what is acceptable and what the consequences of speaking out might be discourage staff from open and free expression on divestment. Whether through explicit policy or social pressure, the outcome remains the same. Free expression by staff members is subdued and productive conversations are effectively restricted.

While the Office of Sustainability’s Sustainability Action Plan provides an important basis for climate action at Princeton, some on campus do not feel that it goes far enough, even if they won’t say so out loud. Leadership on climate requires driving unprecedented institutional change – there are no workarounds.

Many of the respondents shared strong opinions about the University’s so-called ‘leadership.’ One respondent wrote, “it is hypocritical of the [University] to not have a plan to ‘divest’ from fossil fuels in its endowment and other indirect emission sources while it strives to reduce its on-campus carbon emission.”

Abby Nishiwaki / The Daily Princetonian

Other respondents recognized the need for student activism but stressed the difficulty of supporting student efforts, given the culture of restricted free speech. “While I see my own position on this issue as being somewhere in the moderate range, activism from students who push for an extreme shift in current practices is desperately needed if we’re going to get anywhere … It’s often challenging as a staff person to be able to appropriately express my gratitude to students.”

A major talking point against divestment is concern over the endowment. One respondent explained that while they supported divestment, they could see “strategic reasons why this might not be an immediately viable strategy… [especially for] keeping as many folks as possible employed and continuing to offer generous financial aid.”

Yet, the University’s annual endowment returns this year were roughly half of its average annual return over the past decade, while Brown University, which largely divested from fossil fuels earlier this year, saw the Ivy League’s highest annual returns this fiscal year.

Similarly, the Rockefeller Brothers Fund divested from fossil fuels in 2015 and has since outpaced financial benchmarks. The revenue concerns that some divestment opponents pose are unfounded, and the culture of fear around speaking out on divestment keeps these important discussions from happening in the first place.

The Princeton community is not the same space of open and free expression for staff as it is for students and faculty. One respondent wrote, “People who hold precarious positions … don’t need direct threats to their employment to fear speaking out; knowing that your position could be terminated for any reason at any time is threat enough. For people in more secure positions … it becomes a question not of fearing being fired, but of fearing damage to your reputation and more difficulty working with colleagues over the long term.”

Juxtaposed with the University’s policies on free expression, this restriction of speech on such an important issue is unjustifiable, especially since so many staff work in sustainability and the environment. According to the Rights, Rules and Responsibilities handbook, the University “guarantees all members of the University community the broadest possible latitude to speak, write, listen, challenge, and learn… [and] seeks to promote the full inclusion of all members and groups in every aspect of University life.” Do staff members not belong to the University community?

Rights, Rules, and Responsibilities further clarifies, “Faculty, staff, and students … are free to engage in political and civic activities.” The survey responses suggest otherwise.

Of course, there are limits to free expression, such as defamatory speech, harassment, or invasion of privacy. But speaking up about divestment falls outside these parameters. On what basis does the University defend anti-Black racism and the use of racial slurs, even as employees don’t feel they can speak against unjust and detrimental investments that harm all of our lives? On position title? Tenure status? Whether the speech is critical of the University?

It’s time to question Princeton’s romanticized view of free speech. Even if the nature of their positions bars certain staff members from signing public-facing divestment campaigns, staff members should not fear for their jobs for even discussing divestment.

Free speech is not picking and choosing who may contribute to academic and political conversations. Free speech is not limiting discussion of controversial topics. Free speech is fostering an inclusive and open space for dialogue.

After all, climate change does not care about position or title, and neither should free speech — not when our lives are at stake.

Hannah Reynolds is a junior in the Anthropology Department. She wrote this column with research support from Princeton Environmental Activism Coalition members, including Mayu Takeuchi ’23, Katie Forbes ’23, Helen Brush ’24, Lena Hoplamazian ’24, and Justin Cai ’24. Reynolds can be reached at hannahr@princeton.edu.