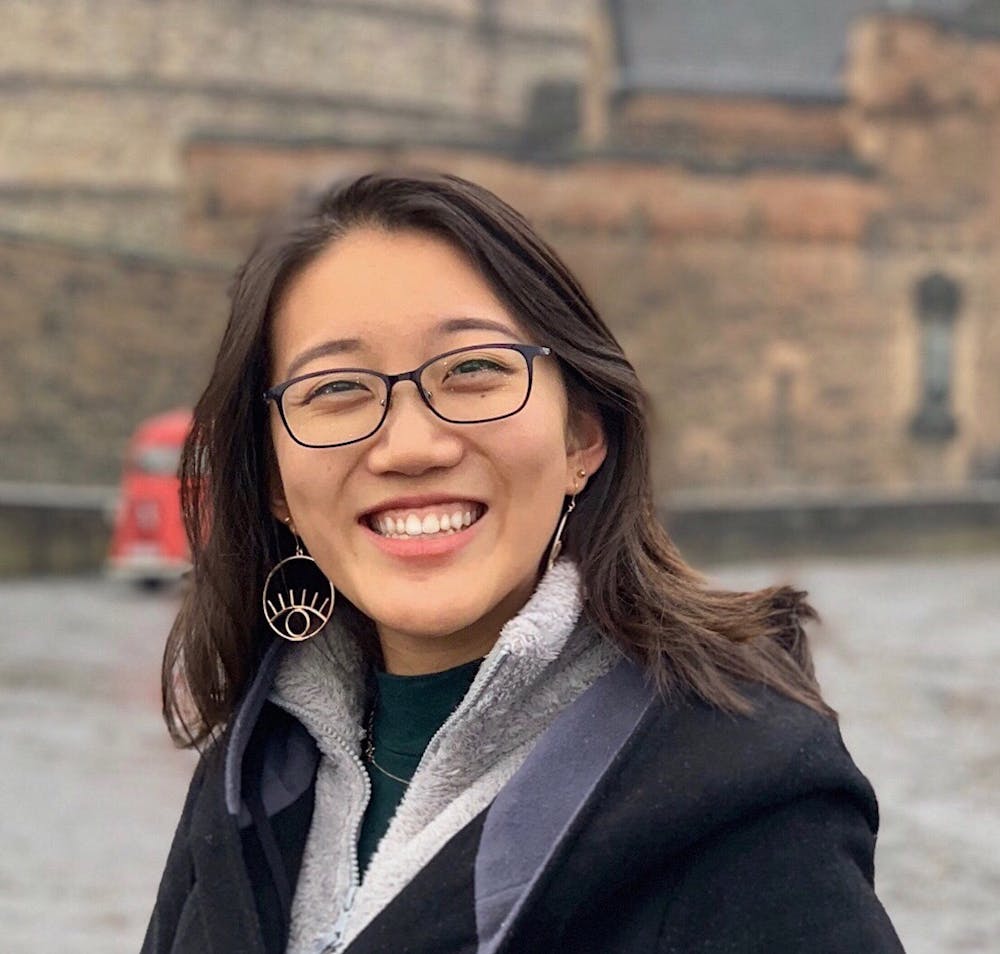

Sophie Li ’21 was named one of two Rhodes Scholars for Hong Kong on Nov. 22, joining 32 winners from the United States and nearly five dozen more from other countries.

Li, who has lived in Hong Kong since the age of three, is a politics concentrator pursuing a certificate in journalism and plans on obtaining a Master of Science degree in Refugee and Forced Migration Studies at the University of Oxford.

The Rhodes Scholarships, established in 1902 through the will of diamond baron Cecil John Rhodes, fully fund approximately 100 students for up to three years of graduate study at Oxford. Widely regarded as one of the most prestigious international scholarship programs, the fellowship selected its entire cohort virtually for the first time in its history this year, as the coronavirus pandemic continues to wreak havoc around the world.

Following Oxford, Li will go on to Harvard Law School, where she has accepted a position through the junior deferral program and hopes to focus on asylum law.

Li’s work at the University — both academically and extracurricularly — has centered around forced migration through the lens of human rights, constitutional law, politics, social statistics, and journalism.

For Li, one of her most seminal academic experiences was SOC 207: Poverty in America, which she took sophomore spring with sociology professor Matthew Desmond.

“It's a class that is quite intense and it pushes you to really step out of the classroom and go beyond a textbook and go in and be a human in the real world for a little while,” she told The Daily Princetonian.

As part of the course’s original sociological fieldwork component, Li focused on poverty among older adults from an East Asian immigrant background. Throughout the interviews she conducted, Li said she began to reflect on the structural inequalities and unequal access to resources that have been woven “deeply within the fabric of elite institutions” among the likes of Princeton, Oxford, and Harvard.

“Professor Desmond is an absolute idol and one of the most impressive, not just intellectuals, but writers and thinkers and all-around people in the world, I think,” Li said. “[His class] showed that there's almost a responsibility to marry rigorous intellectual work with real social impact.”

“If you're given access to such ridiculously elite institutions — the money to be compensated for an Uber ride to an affordable care home or whatever — there are real and rewarding ways to connect them to social issues that exist,” she continued.

In fact, the “hypocrisy” of sorts that is inherent between being an ally of a social justice issue and the significance and honor of the Rhodes is something Li believes she would be remiss not to address.

“The privilege to study abroad begets a commensurate responsibility,” Li wrote in her application letter to the Rhodes Trust. “To amass as many skills and as much knowledge as possible — to become the most effective advocate I can be — to return home, and serve the community that raised me.”

With an eventual Harvard law degree in hand, Li said she hopes to go back to her home of nearly twenty years “where the issues that are near and dear to my heart are sort of in close proximity to where I am.”

“My parents gifted me the ability to study overseas, and my schooling a global curiosity,” she wrote in her personal statement. “But that which really matters — moral clarity, personal conviction, a sense of home defined by values over nationality — Hong Kong and its people gave me.”

Hong Kong, which has over 14,000 asylum seekers, is still embroiled in pro-democracy demonstrations against the 2019 extradition bill that sparked violent clashes with the police.

In the summer after her first year, Li worked at Resolve, a non-profit based in Hong Kong focused on empowering emerging community leaders.

According to Li, her experience there gave her a unique opportunity to engage in grassroots-level work for small and growing organizations early on, which she remarked was diametrically opposed to what many students at Princeton might end up doing: “make a living first and make a lot of money and find a comfortable job and then only when you're settled and comfortable you can sort of do a little bit of nonprofit work on the side.”

Hong Kong today is not a welcoming place for refugees, Li explained, but added that forced migration is “essential Hong Kong history,” where current trends are “indisputably tied” to the millions who fled mainland China in the 1900s.

With this in mind, she continued, it is particularly meaningful for a scholar from Hong Kong to be doing refugee and forced migration studies.

“It doesn't have to be me,” she said. “But I think regardless of who does that there is some level of symbolic value in that happening.”

Li’s extensive list of extracurricular activities include her role as a researcher on asylum applications with the Princeton Asylum Project as part of the Religion and Forced Migration Initiative and her involvement with the Oral History Project on Religion and Resettlement.

For Li, her journalism courses have also given her the opportunity to explore social issues that are exceptionally complex.

In fall 2019, Li took journalism professor Deborah Amos’ course on migration reporting, where her final project focused on a successful Canadian program that helps Yazidi and Syrian refugees work in agriculture.

The paper included profiles on a Syrian family that worked on a plot of farmland in Manitoba and was able to set up a popular farm stand business, as well as Yazidi families who were able to integrate by learning Canadian culture through their placement on Canadian farms.

“Li’s final reporting project … was a masterful examination of work experiences for refugees who come from rural economies,” Amos wrote in an email statement to the ‘Prince.’ “She was passionate in showing that ‘work’ is the experience that smooths integration even when refugees are still struggling with English fluency.”

“Sophie is a dogged investigator with a commitment to long-form journalism,” continued Amos, who herself is an award-winning Middle East correspondent for NPR. “She’s a star.”

Rory Truex, Princeton School of Public and International Affairs and politics assistant professor, first taught Li in his Chinese politics class in fall 2018. Truex said Li immediately set herself apart from the rest, including his graduate students.

“She had a depth of knowledge about the material that exceeded that of my graduate student preceptors,” Truex wrote in his recommendation letter for Li. “Having her in class is like having a second professor in the room.”

Even so, Truex emphasized, Li “never once rested on her laurels.”

In the summer following her sophomore year, Li worked as a research assistant for Truex, conducting research on drug crimes and detention centers in China and analyzing data related to political psychology there.

Even as she joins a cohort of renowned scholars and leaders who have pursued careers in academia, law, business, medicine, and science, Li says she remains deeply humbled.

“The person that I was before 12:42 a.m. on Sunday [the time of her notification] is absolutely no different from the person I was after 12:42 a.m. on Sunday,” she said. “Nothing in my life, nothing that I had done, nothing I had achieved, nothing I hadn’t achieved — changed just because I suddenly became a Rhodes Scholar.”

“I think there's like some assumption that like, if you win something then it changes something about you,” Li continued. “I stand by what I've done and I stand by also what I have failed to do ... but nothing has changed in the interim period to make me more deserving of something than when I wasn't a Rhodes Scholar.”

“In most cases, very few people ever need the Rhodes Scholarship,” she explained. “It's more a question of like, do you want it and can you do something meaningful with it. I knew I wanted it, and I hope to do something meaningful with it.”

Whichever field she ends up in — and whatever she ends up accomplishing — Li says there is just one thing she hopes to be remembered as.

“I put a lot of value in being around nice people. And I've always regretted being mean,” she said. “Being smart is kind of meaningless because if you're smart, you're smart. It doesn't take a whole lot of work to keep up.”

“But I think being nice is something that is honestly actively very hard, sometimes especially when you live in a pandemic and everything is just terrible,” Li continued. “I would love to just be someone who is remembered for being a nice person to be around and that's all you can really ask for.”

In a completely virtual semester, Li has spent the past few months living with friends in upstate New York in a rental — something she acknowledged is a “ridiculous privilege.”

Though the global pandemic has upended any modicum of normality in the school year — her senior year at that — Li said she constantly reminds herself to reset and temper her expectations.

“There are lots of people who've lost their jobs, you know, lost family members, lost their lives,” she said. “Everyone around the world is asking, ‘why me?’ and it's like — at the end of the day — why not you? Like why do we deserve these untouched, perfect lives?”

This mindset, and the willingness to accept setbacks, is something Li said has informed the way she approached the Rhodes Scholarship application — and life in general, especially at an institution where imposter syndrome and the myth of effortless perfection run rampant.

“I have been rejected from so many things you'll never see,” she said.

“I think there's an impression that like, oh, because things have happened to stack up for me in the right way... it's been smooth sailing the entire time,” Li continued, adding that in her first two years of college, she never got an internship earlier than April or May.

“I PDF’d Bridges [CEE 102]. I PDF’d COS 126 [Computer Science: An Interdisciplinary Approach],” she laughed. “Writing Seminar and ECO 100 [Introduction to Microeconomics] are my lowest grades at Princeton.”

“Princeton is really challenging for everyone — everyone suspects that they're the dumbest one or the least social one or the most uncool, right?” she said. “But you really only know about your own failures.”

“Like, I can’t boil an egg. It’s one of my greatest character flaws. And every time I play Mario Kart, I come in 12th place. I’ve been 11th, like, once.”

To her classmates, Li says: “Figure out the few things that you care about. Work hard. Be nice. Don't take yourself so seriously.”

The thing she misses about Princeton? The roasted vegetables at Forbes brunch and her friends, she answered without hesitation.

Ultimately, for this 2021 Rhodes Scholar Elect, she sees herself as a “clown” at heart, someone who just “sort of flows through life.”

Even at the final round group interviews for the scholarship — the “last opportunity to impress the judges” — Li said she found herself playing Just Dance with her roommates.

“The 20 minutes before my group discussion round, I played some very vigorous rounds of Just Dance,” she recalled. “I really think that that was the secret. That was the secret to the scholarship.”

Editor’s Note: The quotes that Professor Rory Truex provided to the ‘Prince’ have been updated.