With less than a month before the presidential election, executives at Twitter and Facebook have made national news for unveiling several measures to combat misinformation, block voter suppression, restrict political ads, and even prevent premature victory declarations. The viability of some of these measures will only be determined after we finish what is going to be a bitterly contested election. Given the flaws within some of these policies, however, there is no certainty they will prevent the disinformation or exaggerated claims that often unduly influence young voters who are increasingly informing themselves via the internet.

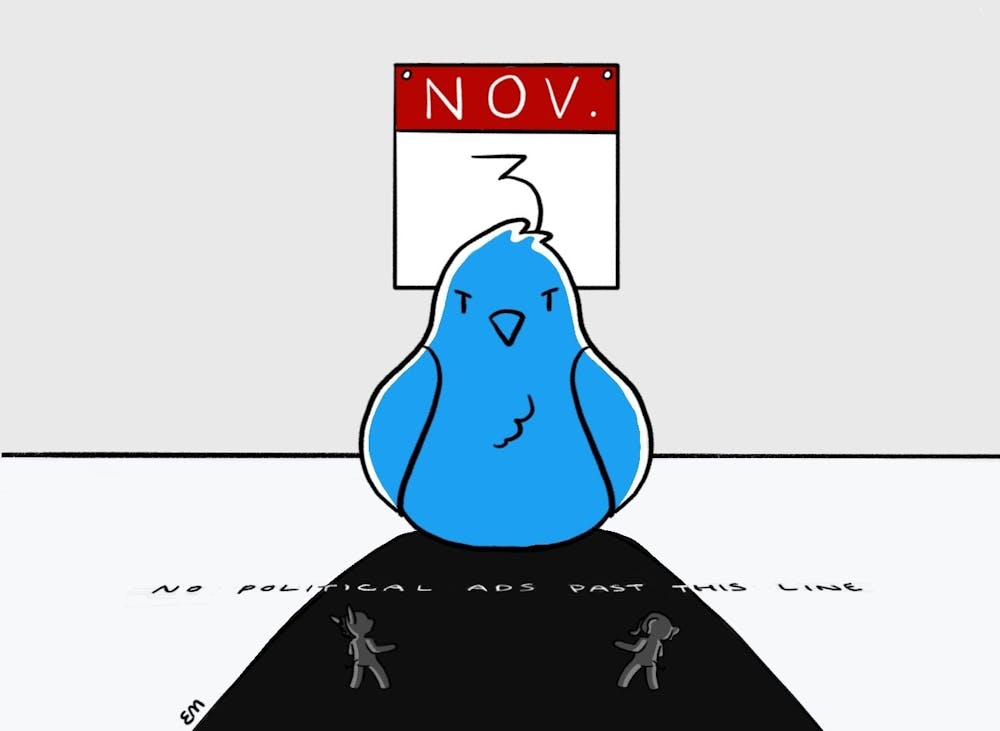

Social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook must take more substantial measures to ensure a well-informed, free, and fair election by enforcing a temporary, scheduled moratorium on political advertisements for at least two weeks prior to the election. While the duration of the moratorium and its application to only the November election (instead of all federal elections, for example) are certainly up for debate, they are nonetheless adequate starting points for such a policy.

Platforms are heading in this direction, but in too timid a manner. Take Facebook. In early September, Mark Zuckerberg announced a ban on new political ads — but only in the week leading up to Nov. 3. Additionally, the new policy will explicitly allow ads that had been bought prior to not only run, but also be edited and even retargeted. Furthermore, Zuckerberg’s refusal to fact-check posts from political figures will likely prevent any retroactive removal of problematic ads, the kinds of which will become more likely as candidates get antsy as the election nears.

Even if they were to craft honest ads, candidates would likely be unwilling to purchase what are likely to be expensive and reactionary ads on the platform this close to Election Day. Finally, recent polls suggest that the vast majority of Americans have had their mind made up for weeks, if not longer, on their candidate of choice. Combined with unprecedented access to early and mail-in voting to avoid illness during a pandemic, Facebook’s plan seems to be superficial.

Despite how problematic this particular policy might be, this idea from Facebook and other companies can be reduced to a simple principle: Voters should be shielded from influence when very close to casting their vote. The best way to extend this protection to the digital realm is not through policies that undermine themselves, but through a temporary, scheduled moratorium on political ads.

Such a policy already has over a century of precedent in the United States, albeit in a more physical form. So called “buffer zone” laws originated in the late 1800s to prohibit electioneering, campaigning, and, most importantly, intimidation within a specified distance of polling locations. Now, all 50 states have some form of this law on the books. Just this week, a federal judge upheld a Kansas law of this type, prohibiting the aforementioned activities within 250 feet of the polls.

While voting remains a predominantly analog process, voter education, information, and, yes, intimidation are now largely digital endeavors. Preventing all political ads for a specified time period before national elections would prevent candidates and the monied interests that support them from leveraging access to voters’ profiles and online activities by targeting them. In 2020, these manipulative tactics take on much more subtle, prolonged, and pervasive forms and ought to be combated just the same.

Such a system would come with benefits and responsibilities. During the moratorium, private users would still be free to express their opinions if they wished, and they could converse with one another with confidence that the person on the opposite screen is not being tempted away from constructive conversation by partisan clickbait. However, it would be up to users to use established facts, institutional research, and common decency to identify exaggerated claims and admit when using them.

This moratorium would also allow media outlets and journalists to regain the singular role of releasing election results and apprising voters of what candidates are doing. Far from resting on their laurels, these same organizations will have to refrain from indulging candidates who might use the power of their office to drum up crises or stunts that force their message into the social media bubble. A final benefit of this policy is it may convince candidates to run on substantive policy because such a strategy builds support over time and is much more sustainable than the buzzwords placed throughout social media ads.

While these organizations will still have ads on other media, such as television, at their disposal, a ban on social media advertising will be uniquely positioned to combat the spread of misinformation. Politicians will also have to make their case to those Americans online before the moratorium and trust that their records, not their empty words, will carry the day.

If these companies were committed to upholding and protecting the very democratic system that has allowed them to prosper, they should have begun these efforts years ago. That option being impossible now, it is crucial voters — particularly young, social-media-savvy voters — recognize that attempts to make social media more hospitable for democratic exchange will only succeed if platforms undertake structural changes, especially during election season.

In this election, and every one going forward, we must recognize that democracy does not survive unless we support it with our creativity, our grit, and our full commitment. The protection of our democracy might be digital, but it is no less real.

Dillion Gallagher is a sophomore intending to concentrate in the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs. He can be reached at dilliong@princeton.edu.