On Monday, University President Chrisopher Eisgruber ’83 wrote that the University is “preparing for the possibility that we will be able to welcome back significantly more undergraduate students in the spring.”

“These results are consistent with reports from many other American campuses with extensive asymptomatic testing protocols. On campuses that have instituted and followed responsible public health guidance accompanied by extensive testing, there is as yet no evidence that the virus is spreading in instructional settings or in dormitory housing,” he wrote.

Deputy University Spokesperson Michael Hotchkiss did not elaborate when asked which cases Eisgruber was citing, but he noted that administrators “maintain open lines of communications with colleagues at colleges and universities across the state and around the country.”

This fall, Princeton was one of the few universities in New Jersey to adopt a fully online model for undergraduates. The College of New Jersey in Trenton also opted for entirely-virtual instruction, though students eligible for emergency housing or conducting “upper-division research” may live on campus.

New Jersey’s 14 other four-year universities with at least 5,000 students all settled on hybrid fall plans, with some in-person instruction.

As the University prepares to release its spring plans in early December, The Daily Princetonian takes a look at how New Jersey’s largest schools have fared this semester.

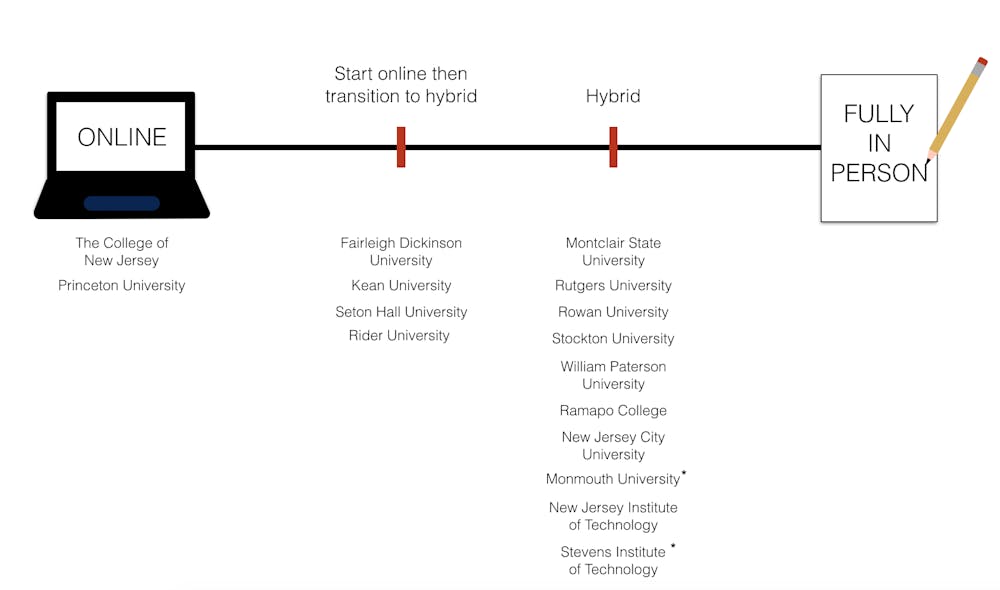

The fall 2020 plans of New Jersey colleges and universities with enrollments of over 5,000.

* Monmouth switched to fully-virtual learning for two weeks following an off-campus super-spreader event, and Stevens Institute of Technology only adopted the hybrid model for first-years and transfer students.

Design credit: Anika Agarwal / The Daily Princetonian

Hybrid from the start

Rutgers University, Montclair State University, and Rowan University are New Jersey’s three largest universities, with enrollments of about 51,000, 21,000, and 19,000, respectively. All three implemented varying degrees of in-person learning. Even with their large enrollments and hybrid classes, authorities haven’t identified any significant COVID-19 clusters or spikes on any of the campuses.

Montclair State has managed to limit the spread of COVID-19, with only 24 cases among students and two among employees since fall classes began on the emphatically “open” campus. Montclair State reduced on-campus occupancy by a third, with 3,499 students living in residence halls, compared to 5,200 in a typical year.

Montclair State has also implemented a wide range of course delivery strategies. While all students are required to complete a daily virtual health check-in, only students participating in “high contact” activities must be tested for COVID-19.

Though Montclair State recently canceled its study abroad program, the college has yet to release concrete spring plans. The school has written, however, that “when New Jersey enters Stage 3 the University may [further] expand occupancy.”

Rowan has also prioritized in-person and hybrid learning wherever possible, though classes deemed higher risk, such as physical education and theatre, are being taught online. Other courses, including labs where “physical presence is mandatory,” have been offered in person, and most courses have adapted a “Hybrid-Flexible” model, which allows students to choose between face-to-face and virtual attendance.

Students with fully-virtual course loads may still live on campus, and Rowan has seen 205 COVID-19 cases on campus since the start of the school year. Twenty-five have been reported this month.

Like several other schools in the state, Rowan has enacted limited asymptomatic testing, conducting 319 asymptomatic tests with two positive results thus far. The school aims to test one percent of its Main Glassboro Campus population weekly through an opt-in program.

Rutgers has conducted a greater proportion of classes online, with some classes in-person. Rutgers-Camden Interim Chancellor Margaret Marsh noted, “we remain at Stage 2 of our statewide recovery … classes that can otherwise be conducted through remote instruction must continue to be offered remotely in the fall.”

Rutgers has adopted a “targeting testing approach,” in which a committee determines “which groups of students or employees should be recommended and/or required to complete testing” for “strategic reasons.” In total, New Jersey’s flagship university has confirmed 21 cases among employees and 324 student cases out of 38,000-plus administered tests.

Under 20 students have tested positive at Rutgers’s smaller Newark, Camden, and Biomedical and Health Sciences (RBHS) locations. At Rutgers’s New Brunswick location, where 950 of some 50,000 students are living on campus this semester, 273 have tested positive.

Rutgers-New Brunswick has already released spring plans, anticipating an additional 5,000 students on campus “with half-occupancy in older apartments and all suite halls” and “additional opportunities for in-person classes.”

Other New Jersey universities following the hybrid model this fall include William Paterson University, Stockton University, Ramapo College, New Jersey City University (NJCU), Monmouth University, Stevens Institute of Technology, and New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT), which maintain enrollments ranging from 5,600 to 11,500 students.

Most students at Stevens Institute of Technology are taking classes online, and the college is only permitting first-years and transfer students to reside on campus. These students, as well as incoming graduate students, have experienced a mix of in-person, socially distanced hybrid learning, and online instruction.

Similarly to Princeton, Stevens conducts weekly testing for those on campus. Only six of the over 9,300 tests administered on Stevens’ campus this semester have returned positive results.

William Paterson and Ramapo have prioritized in-person instruction for lab courses and other hands-on instruction, while NJCU has prioritized providing first-year and second-year students an on-campus experience. NJIT has adopted a “converged learning” model, in which students may choose between face-to-face instruction or synchronous video attendance.

Despite supporting some in-person learning, these schools have yet to report on-campus COVID-19 clusters or spikes in cases — with William Paterson, Ramapo, NJCU, and NJIT currently reporting between 11 to 23 COVID-19 cases since the fall semester began. NJIT experienced a COVID-19 scare in late September, after its environmental sampling protocol revealed COVID-19 in the sewage of one of its residential halls.

Through its asymptomatic testing program, NJIT tests 320 members of its on-campus student body each week. In the 14 days prior to Oct. 22, two new cases of COVID-19 were identified.

Stockton and Monmouth, with 10,000 and 6,000 enrolled students respectively, have reported more cases. Stockton has reported 118 cases among students and four among employees since September, under a mix of in-person, remote, and hybrid instruction.

Monmouth has reported 188 cases among students on campus, 161 among non-residential students, and six among employees.

Many of Monmouth’s cases have been linked to an off-campus superspreader event. Initially, this 125-case off-campus cluster forced Monmouth to suspend its hybrid plan, with a two-week shift to virtual instruction.

Soon after, however, Monmouth President Patrick F. Leahy released an update, announcing the university would be “restarting in-person and hybrid instruction … particularly because extensive contact tracing efforts have not shown evidence of intergenerational transmission among our University community.”

Stockton, Monmouth, Ramapo, NJCU, and NJIT have yet to release concrete plans for the spring semester. William Paterson President Richard Helldobler announced in mid-October that the University would “continue to offer a mix of course delivery options for the Spring 2021 semester,” with a slightly-adapted schedule and no spring break.

From virtual start to hybrid shift

While some universities began the semester with in-person classes, Kean University, Fairleigh Dickinson University, Seton Hall University, and Rider University started with online classes before transitioning to a hybrid system.

At Kean, the fall semester launched with remote instruction on Sept. 1, with “about 22 percent of courses moving to face-to-face or hybrid instruction” 20 days later. Fairleigh Dickinson began its semester in mid-August and began to offer “a limited number” of in-person courses on Sept. 14. Rider held classes remotely for three weeks prior to shifting around 20 percent of courses to an in-person or hybrid model.

Seton Hall made this transition more quickly, with mostly remote instruction from Aug. 24 to 30 and hybrid instruction beginning on the Aug. 31. The college has implemented a rotation system, in which students who choose to take a hybrid schedule “will be assigned a group letter (A or B) or group number (1, 2, or 3)” and “rotate between meeting in-person and attending remotely.”

Kean and Rider have not released definitive spring plans. While Fairleigh Dickinson has canceled study abroad, the school plans to offer a hybrid model again in the spring and “hope[s] to be able to offer more in-person courses than we did in the fall.” Seton Hall has also not released concrete plans for spring instruction, but the college did elect to cancel spring break.

Of the schools in this category, only Fairleigh Dickinson and Seton Hall offer asymptomatic testing, which is performed through random surveillance. While Kean does not test asymptomatic students, Union County operates a free drive-through testing site on its campus.

At Seton Hall, 17 students have tested positive, of 2,806 tested. Four students have tested positive on each of Fairleigh Dickinson’s two campuses, with 563 negative tests, and one employee has tested positive since the start of the semester. At Kean, at least three on-campus students, seven students who commute to the campus, and 12 remote-learning students have tested positive for COVID-19, and two employees have reported positive test results.

Rider University received criticism for its lack of testing earlier this semester, with The Rider News recently reporting that the university had “tested only 12 students for the coronavirus on campus since the start of the semester” and calling the relative absence of tests “a worrying sign for residents and a clear indicator of the uncertainty of campus safety.”

In mid-October, the school began its first week of random surveillance testing and administered 45 tests without any positive results. At least one student and two employees have tested positive for COVID-19 on Rider’s campus this semester.

What might all this mean for Princeton?

In his mid-semester message, President Eisgruber wrote that campuses with responsible public health guidelines and extensive testing have not seen the spread of COVID-19 in instructional settings or dorms, with “the vast majority of cases that arise being traceable to off-campus social events.” Planning to open an on-campus testing laboratory next month, the University says it is preparing to bring back “significantly” more students next semester.

A decision is expected in the first week of December. While writing that the results thus far have been promising, Eisgruber made clear colleges across the country must strive to keep things that way.

“Though the early fall has gone well on this campus and for many of our peers, the next six weeks will provide additional, and crucial, information,” he wrote. “Challenges will likely increase as colder temperatures force people indoors, the flu season begins, and people gather for holiday celebrations.”

Though the University is monitoring other campuses, Hotchkiss noted that it will still need to “make decisions based on our particular circumstances, including the state of the pandemic in the local area and New Jersey, the structure of our educational program, our campus COVID testing program, and the configuration of our campus and facilities.”