Disney’s live-action remakes have always been contentious. On one hand, the fans want the remake to stay true to the original and recapture the magic and nostalgia. On the other hand, because recapturing that magic and nostalgia is almost impossible, the audience expects new elements to be introduced, either to the characters or to the plot, in order to justify the remake’s existence.

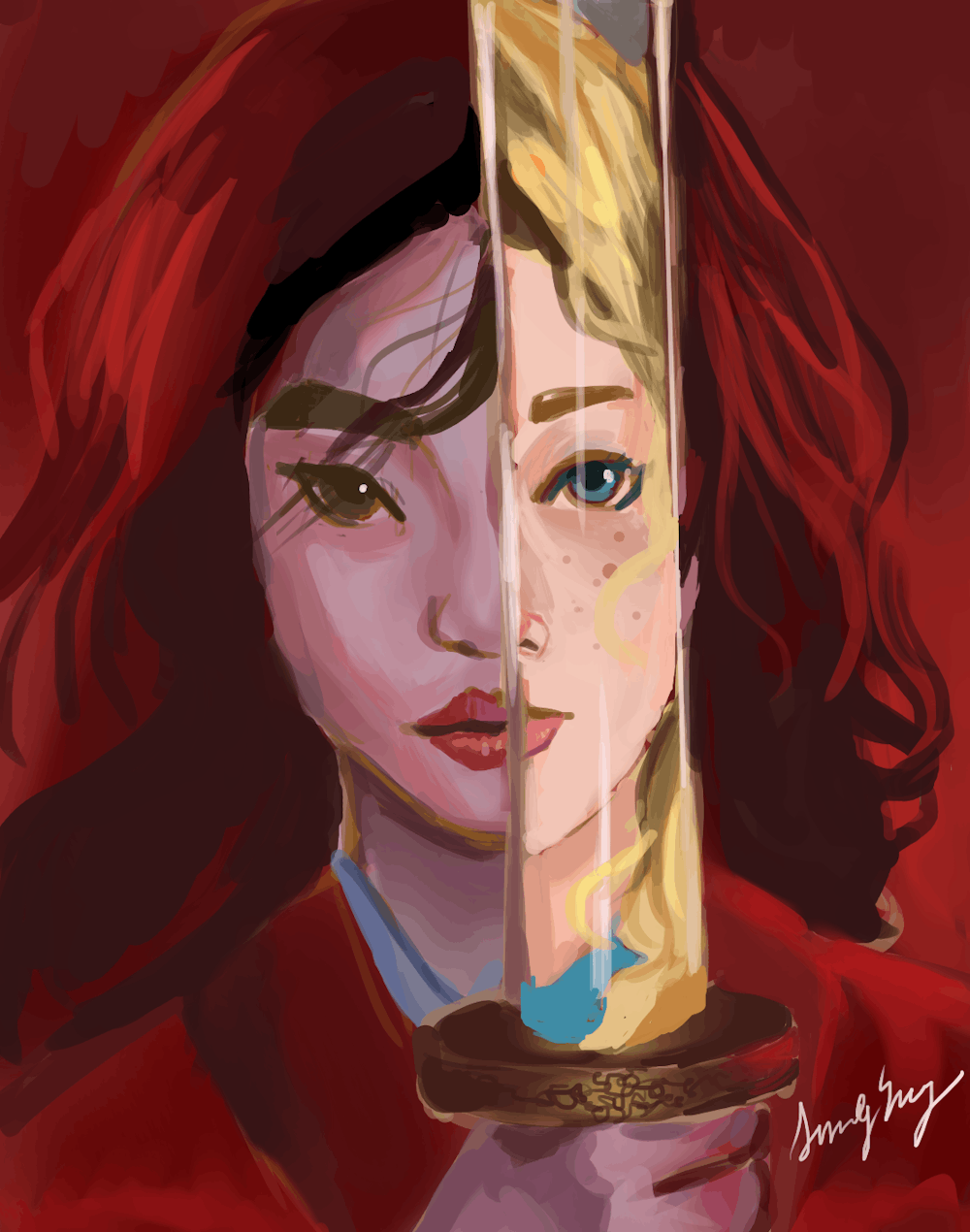

The ultimate goal of these remakes is to breathe new life into the story, but for the 2020 remake of “Mulan,” Disney took expectations one step further by promising a more culturally authentic and realistic version of Mulan’s story. The new film still follows Mulan as she takes her father’s place in the Chinese army, posing as a man, but the threat China faces is now the Rourans, led by Bori Khan and aided by an alienated witch possessing dark magic, rather than the 1998 movie’s use of the Huns.

The biggest, immediately observable changes were the removal of all the musical numbers, the elimination of the character Mushu, and the splitting of Mulan’s love interest, Li Shang, into two different characters. All three decisions led to a massive outcry from fans. The writers and director argued that these choices were conducive to making a grittier historical drama and would fit the new tone better, but the heart of the problem has nothing to do with the overall tone. What the songs and characters of Mushu and Li Shang mainly added were character development and interactions, meaning and impact within the narrative by setting the mood of certain scenes, and comic relief that gave the movie room to breathe. Without these elements, there is an emotional void that the remake just doesn’t try to fill.

One of the most iconic scenes from the original comes right after the matchmaker has proclaimed that Mulan has brought dishonor on her family, when Mulan sings “Reflection.” Through the song, the audience understands her internal conflict, which drives her character for the rest of the movie.

In the live-action version, however, this scene is cut out completely, directly skipping to her father receiving the call to war. The audience doesn’t really see or feel Mulan’s internal conflict at all throughout the movie except for a couple of references to her inability to embody the “truth” of who she is. The original scene holds a lot of emotional weight for the character and has an impact on the film that the remake doesn’t even try to make up for.

Similarly, there’s a scene in the original where Mulan and the other soldiers are singing “A Girl Worth Fighting For,” a lighthearted and funny song that fits their jaunty mood, as they are fresh from training and are still filled with excitement and hope, until they stumble upon a village that has been completely destroyed by the enemy. This jarring juxtaposition shifts the tone not only in the scene itself, but for the rest of the movie, as the soldiers and the audience realize the true horrors of war. However, in the live-action remake, there is no song, so there is no juxtaposition, and the film doesn’t do anything to compensate for that. While this scene is a powerful moment and a turning point in the animated version, the scene feels much less impactful for the film and the audience in the live-action version.

By getting rid of these moments of comic relief from the original, the character development suffers. In general, the remake’s characters are terribly unconvincing. The villains aren’t compelling since they’re barely given any lines of exposition — their backstories and individual motives are weak and underdeveloped, which doesn’t make for a rich and complicated story arc. Although Ling, Yao, and Chien-Po are still in the movie, they feel shoehorned in. Their characterizations and personalities are never explored, and they only appear in a few scenes to begin with, so there’s no sense of a real bond between these characters, and the audience isn’t invested in them.

In a later scene, after getting kicked out of the army, Mulan goes to warn her battalion about Bori Khan’s movements, and her “friends” are the first to stick up for her and proclaim their trust in her. However, this scene feels empty — without the development of friendship between them through earlier, more playful moments, it is unconvincing that these soldiers would believe in her. It almost feels like these characters were included just to appease those who still wanted some kind of romantic interest for Mulan.

All of these elements that were cut out were supposedly cut in order to preserve the authenticity of the story and culture through a more serious film, but by having an all-white team behind the camera, the movie dug its own grave. Despite promising to be more culturally authentic, Disney hired a white director, a white costume designer, four white screenwriters, a white composer, a white cinematographer, a white film editor, and a white casting director. Even the 1998 movie version had one female Asian writer. Instead of hiring Asians who actually grew up in Chinese culture, Disney had the writers and designers do research in an attempt to soak up the culture, which led to a Chinese story with many Western elements and a lot of misused Chinese concepts.

In the 1998 film, Mulan finds clever ways to overcome the limits of her strength in order to become a great warrior. Her character in the live-action movie has been completely altered so that she is naturally gifted — the movie implies that because she was born with such strong chi, she basically has supernatural abilities. From a Chinese cultural perspective, there are several problems with this. Chi is life force or energy flow, and although there is the Taoist belief that you can gain supernatural abilities by using chi, this is achieved by cultivating one’s chi; these abilities are not something you are naturally gifted with. The only way to cultivate your chi is through hard work, which is an essential aspect of Chinese culture — you can only attain success through hard work.

Even though she does go through training, the movie still shows that Mulan is born special with particularly strong chi, which she makes great efforts to hide for the first half of the movie. As soon as she stops repressing her chi, she suddenly turns into a badass who can defy the laws of physics. It feels like the writers kept throwing around the word “chi” just to make the story seem more steeped in Chinese culture, but if anything, the original version of the story where she has to work hard to build up her skills is more in line with Chinese beliefs.

The phoenix in the remake is the emissary of the Hua family’s ancestors and is supposed to replace the character of Mushu as a more culturally authentic figure. However, the way that the phoenix is used symbolically in the story is entirely Western. Near the beginning, her father talks about phoenixes rising from the ashes, and this is paid off at the end of the movie when Mulan emerges in the final confrontation to defeat Bori Khan, and the phoenix flies behind her in such a way that she appears to be the phoenix rising. This is fantastic imagery, but there is one huge problem — the concept of a phoenix being reborn from flames is purely from Western legends and has nothing to do with phoenixes in Chinese legends. It seems that the writers included the phoenix with the Western concept of in mind, without regard for what the phoenix actually represents in Chinese culture.

The phoenix itself feels shoehorned in, as it does basically nothing throughout the movie. In a way, it serves as a deus ex machina, because it always appears when Mulan needs to be pointed in the right direction, but that’s also all it does — lead her in the correct geographical direction. There are some metaphorical implications to that, but it doesn’t serve the plot in any other manner or develop Mulan’s character, either.

The live-action remake of Mulan tries to incorporate many new elements with good intentions, but ultimately, the movie is poorly executed. It doesn’t work as a film that elicits nostalgia, it doesn’t work as a historical drama that explores Chinese culture, and it doesn’t even work well as a stand-alone film, separate from the original. The remake is disappointing in almost every way, somehow achieving less than the animated movie does despite its 20 extra minutes of runtime. With its mixed reviews and underwhelming reception in mainland China, this hopefully signals to Disney and other production companies that representation is just as important behind the scenes as it is on screen.

You can still stream “Mulan” (2020) now by paying the steep price of $29.99 on Disney+.