Amid a year of crisis and protest, there is a real desire for progressive and radical change. It is disappointing, then, that as we near the 2020 United States Presidential election, we are once again stuck with two candidates who do not reflect the energy of the progressive movement.

Within a well-established two-party system and without significant electoral power, progressives are forced to operate both inside and outside the United States’ political system, working with Democrats while also pushing their boundaries.

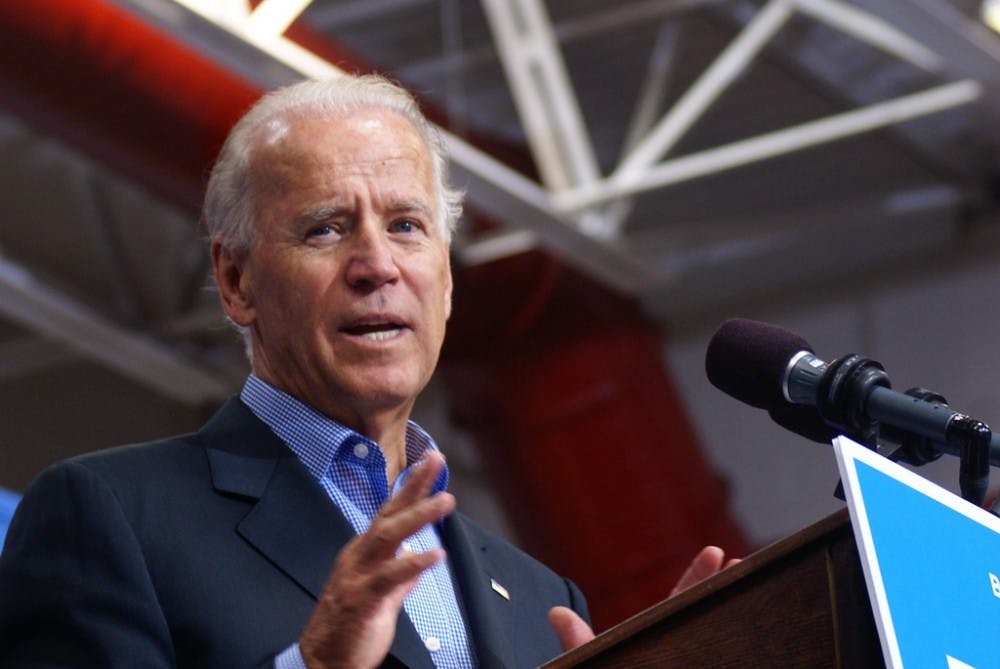

Even so, ever since Joe Biden was became the presumptive Democratic nominee, progressives have expressed doubt about voting for Biden as the lesser of two evils. Whether it be because of Tara Reade’s sexual assault allegation against him or his record of opposition to court-ordered busing, the Anita Hill hearings, the 1994 crime bill, the USA Patriot Act, or the Iraq war, Biden harshly contrasts with Bernie Sander’s progressive and revolutionary potential.

Yet, I believe that if our aim is to challenge the status quo, and especially if we live in a swing state, we need to take into account the consequences of our inaction.

By voting strategically for Biden, we oppose a far right government that will hurt the most vulnerable segments of society far more than a Biden presidency would. As bioethics professor Peter Singer said on NPR this summer, “if the only way to prevent something very bad happening is to do something which would itself be bad but not as bad as the very bad thing that you’re trying to prevent happening, then you’re justified in doing the lesser evil rather than allowing the greater evil to occur.”

In November, we will not only be voting for president but for a whole range of government administrators, appointed judges, appointed directors of the Environmental Protection Agency, advisors, and policies that result from his presidency. We should be voting for someone who, as Angela Davis said in a 2019 interview, “can be most effectively pressured into allowing more space for the evolving anti-racist movement.”

This does not mean that we should settle for ‘lesser evil’ voting. As Noam Chomsky argued in 2016, “the left should devote the minimum of time necessary to exercise the [lesser evil voting] choice then immediately return to pursuing goals which are not timed to the national electoral cycle.”

The electoral system has long been broken. And while voting for the lesser of two evils is a necessary act in this election, of greater importance is the need to rethink and reshape the societal structures that force us to make such an offensive decision in the first place.

This fall, as Princeton students are spread out across the country, we have the opportunity to take a hard look around us and consider what we can do for our communities and our country that will bring about the change we need. If, like me, you’re tired of the lesser-of-two-evils dilemma that arises every four years, take remote learning as an opportunity to promote instant run-off voting, otherwise known as ranked choice voting (RCV), in your local community.

The lesser-of-two-evils dilemma is just one of the pitfalls of plurality voting. It forces each voter to pick only one candidate to support. This means that similar candidates often end up splitting votes and losing to less popular alternatives.

In a RCV election, voters rank candidates in order of preference. This is followed by a series of instant runoffs, in which the last-place candidate is defeated and ballots cast for that candidate are added to the number of votes for the next-ranked candidate on each ballot. This process means that RCV rewards candidates who can win second and third choices, in addition to first choices from a large core of supporters, a process that our current plurality voting system forgoes.

Already, local municipalities in 26 states and nine countries have implemented RCV to some extent, whether it be in presidential primaries, party elections, state elections, local elections, or military and overseas voting. Instead of voting against candidates, voters in these areas can feel comfortable voting for the candidates they truly believe in.

In a 2013 Rutgers-Eagleton Poll, respondents in cities that used RCV reported that candidates in local city elections spent less time criticizing opponents than in cities that did not use RCV. Five percent of these respondents said that candidates criticized each other “a great deal of the time” as opposed to 25 percent in non-RCV cities.

The coming months are going to shape not only politics, but also, as the climate crisis and pandemic intensify, the future of life on this planet. It is beyond frustrating to swallow our anger and disappointment at how the country’s institutions have failed us this election and to vote for a man for whom only 4.5 percent of Princeton students said they would vote for. But it is also an opportunity to go beyond voting to make a better world. So vote for the lesser of two evils, then break all hell loose to protest his faults and change the voting system, so that you can vote your heart in the future.

Anna Hiltner is a sophomore. She may be reached at ahiltner@princeton.edu.