Shortly after a white student’s use of the n-word on social media provoked intense backlash, administrators asserted that the University permits certain uses of offensive slurs — including language that runs “contrary to Princeton’s commitment to stand for inclusivity and against racism.”

Many students criticized the administrators’ statement, which the University community received on July 28, arguing that an institution committed to standing against racism should not permit hate speech.

The message, sent by Vice President for Campus Life Rochelle Calhoun and cosigned by five other administrators, offered the University’s response to “a number of recent statements, publications, or postings on social media [which] offended and insulted many members of our community.” According to Calhoun, the administration “assessed those brought to our attention” and “concluded that they do not represent violations of University policy.”

Without mentioning any specific instances, Calhoun went on to write, “even if certain instances of the use of offensive language — including racial, ethnic, gender, or other slurs — may be protected by our policies, depending on the context, they are upsetting, damaging, and unconstructive, and do not match the values of our community.”

The message came amid national debate about a recent op-ed, in which classics professor Joshua Katz described the Black Justice League (BJL), a Black student activist group active on campus from 2014 to 2016, as a “local terrorist organization.” President Christopher Eisgruber ’83 condemned Katz’s language but affirmed Katz’s right to disparage the group.

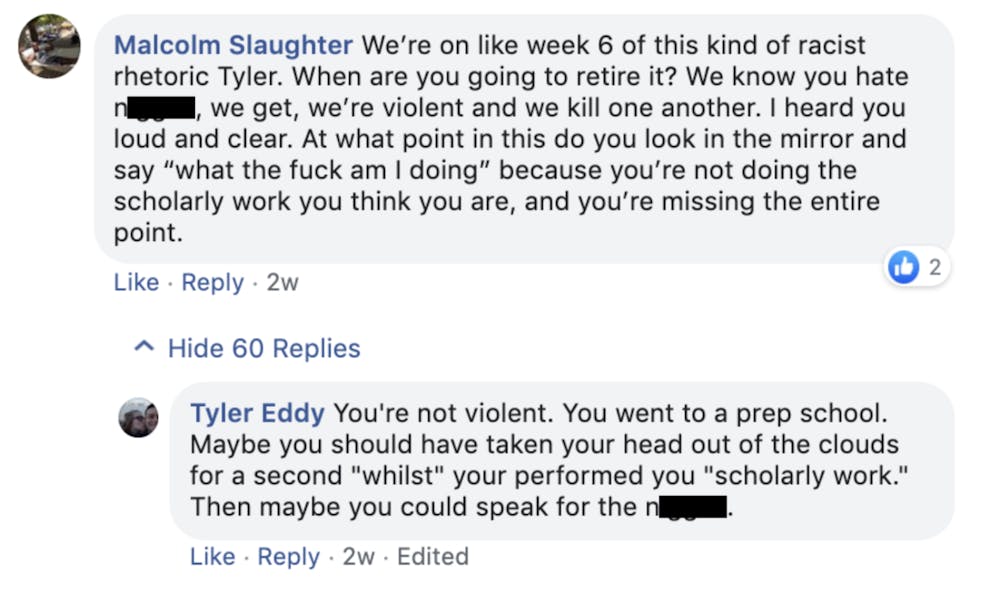

Calhoun’s email also followed a public Facebook comment from Tyler Eddy ’21. In a Facebook dispute about the New York Police Department’s recently disbanded Anti-Crime Unit, Eddy told Malcolm Slaughter, a Black man, that judging by his preparatory school education, he was “not violent” and could not “speak for the n*****.”

A screenshot from Eddy’s Facebook post.

The rising senior went on to comment on the same Facebook post, “Call me old fashioned, but I come from a time when you had to use the ‘hard r’ for it to be considered a racial slur.” Though he told The Daily Princetonian, “I made a mistake” and regrets the harm he caused others, Eddy still defended his right to use the word.

Slaughter, a Fordham University graduate, told the ‘Prince’ he was “very disappointed and disgusted that he’d stoop that low” but unsurprised.

“Tyler has been engaging in a lot of anti-Black/anti Black lives matter rhetoric since the start of the protests,” Slaughter wrote in a statement. “I’ve been debating with him back and forth — trying to offer an alternative perspective on Black lives matter and the protests — to which he responds with very alt-right rhetoric.”

Deputy University Spokesperson Mike Hotchkiss clarified that Calhoun’s email “was written not as a response to any single incident but as a contribution to broader efforts to foster a campus climate of mutual respect.”

In a July 20 op-ed, Eisgruber expressed a similar message, as he expanded upon his previous condemnation of how Katz had described the BJL.

“I was among those who found [Katz’s] statement irresponsible and offensive,” Eisgruber wrote. “Our policies, however, protect Katz’s freedom to say what he did, just as they protected the Black Justice League’s. He can be answered but not censored or sanctioned.”

Black Ivy Stories and a Change.org petition

Eddy, a Marine Corps veteran, met Slaughter at Harvard University in 2016 through the Warrior-Scholar Project, a group seeking to empower former service members transitioning to higher education.

“I regret that I had even allowed myself to consider that the character or experiences of the person I was talking to had any weight in their argument, let alone my use of that word when it was completely unnecessary,” Eddy wrote.

Despite conceding that his use of the slur was needless, Eddy insisted on his right to use it. Since Slaughter had used the n-word first, Eddy claimed, his subsequent comment was merely “parroting.”

“There’s people that strongly believe my use of the word, with just as much moral conviction, shouldn’t be considered wrong because of the direct way that a Black man had stated at first and a white man parroted it,” Eddy asserted. “To acknowledge that that is wrong in any kind of way is to acknowledge that there’s racial differences that we can’t move past, that are just set in.”

When asked to comment on Slaughter’s characterization of his politics, Eddy wrote he doesn’t consider himself “to even be right wing.”

“With friends and family in Canada and the US, from the Marines and at Princeton, I am labeled a liberal just as much as I am a conservative,” he added.

A day after Eddy’s comment, the Instagram account @blackivystories, which boasts over 22,000 followers and displays anonymous, personal stories of Black students at Ivy League schools, posted a submission in which a Class of 2023 member expressed “total shock” that Eddy “is allowed to make these comments so openly and without any repercussions from the University.”

The post has garnered over 200 comments, the vast majority of which tag the University’s Instagram account. At the time of publication, 27 of the last 50 posts on @blackivystories — or 54 percent — relate to the University, one of the eight schools in the Ivy League. None of the tagged posts are viewable on the University’s own account.

On July 22, Sarah Elkordy ’21 created a Change.org petition, titled “Discrimination Hearing for Princeton Student Tyler Eddy on Use of N-Word on Social Media,” which has amassed over 1,500 signatures. The ‘Prince’ was unable to verify how many signatories are affiliated with the University.

“Many students have voiced their strong disagreement and condemning of Tyler Eddy’s words and stances online due to the discomfort and strong emotional responses they cause, and actions like these must be met with proper consequences,” the petition’s description reads. “This petition is a call for action from the University on this subject matter and to show the zero tolerance that true Princeton students have for racism and oppression by our members on or off campus.”

Shortly after its creation, Eddy acknowledged the petition on Facebook. He posted a series of screenshots with the caption: “Should I sign it?”

While the University did not offer comment on Eddy’s use of the slur, the Scholars Institute Fellows Program (SIFP) sent a message to all members announcing Eddy’s departure from future group settings. SIFP is composed of “first-generation and low-income students, as well as military veterans and transfer students” seeking out solidarity among other underrepresented backgrounds.

In an email obtained by the ‘Prince,’ Associate Dean of the College Khristina Gonzalez and her colleagues reiterated their expectation that the community’s “shared ethical context” be honored.

“In SIFP, we have all chosen to be a part of a group in which the speech that we use builds, rather than destroys relationships,” the email reads. “Certainly, we may disagree. But these disagreements must always remain grounded in a shared affirmation of each other’s humanity.”

In her message, she went on to explain that the unspecified individual — whom Eddy confirmed to be himself — had agreed to “respectfully refrain from attending SIFP activities and events, as this post, and a broader pattern of engagement, violates our shared commitment to one another.”

Gonzalez clarified that “staff members … will, of course, still provide support to this community member,” explaining that they “care about and remain committed to their well-being.”

When asked to comment on the announcement, Gonzalez stressed, “it is very important to me that students know that our team works to live and lead with the values that we espouse, like inclusiveness, respect, justice, and compassion.”

“Last week, after a number of conversations with members of SIFP, it was clear to me that I needed to address an issue that was directly affecting many of our students in the SIFP community — and to do so in a way that clarified and put into practice these values,” Gonzalez wrote in a statement to the ‘Prince.’

“The action steps outlined in our email are intended to preserve this ethos, which is fundamental to our broader work in [Programs for Access and Inclusion] of striving toward a more just, inclusive campus (and world) in which all of our students are empowered to thrive,” she added.

Students react to Calhoun’s statement

As the social media firestorm surrounding Eddy’s original comments persisted, students again took to Twitter and Facebook to voice dissatisfaction with Calhoun’s statement, sent five days after Elkordy released her petition.

Calhoun had written that the administration would “not allow the important values of inclusivity and free speech to be pitted against each other,” a sentiment Eisgruber also raised in his op-ed.

Some students, however, disagreed with that premise, arguing that free speech ought to have more stringent limits when it comes to hateful language at a University that claims to stand for inclusivity.

“I think their response reveals just how warped the University’s conception of free speech is, because they clearly value this abstract principle more than the well-being of the students who make up the Princeton community,” said Shannon Chaffers ’22, an associate opinion editor at the ‘Prince’ who has been vocal in denouncing racism in academia.

“It’s frustrating to be told we have to accommodate racist statements from peers and professors based on the false premise that excluding racism in our community will hinder our functioning as an academic institution,” she added.

Seven students delivered a similar message in an op-ed Thursday night, writing that the University’s response “will invariably embolden individuals to use racial slurs.”

Elkordy said she started the petition because of what she sees as the danger of unrestrained free speech at the University.

“I was really tired of students like Tyler thinking that they could say whatever they wanted to about other students and hide it under the guise of freedom of speech,” Elkordy told the ‘Prince.’ “I believe there’s a strong difference between freedom of speech and hate speech, and what they’ve been posting on their social media and our listservs are threats and harassment to our Black students and students of color.”

Elkordy described the administration’s response and Calhoun’s email as “disappointing but unsurprising.”

“I certainly won’t stop fighting for justice against Eddy and his actions, and I hope that one day the University will actually open their eyes and do what’s best for all their students, not just the white ones,” she added.

On July 30, the Instagram account @dearpwi published a 10-slide post to its nearly 30,000 followers about the University’s response, asserting, “A school that claims to value diversity and inclusion cannot protect hate speech.”

“Princeton simply cannot function while failing to protect the livelihood of the Black students it claims to welcome,” the final slide reads. “But the prospect of functionality was shattered the moment the institution decided to admit people unwilling to respect ‘Princeton's inclusivity and stance against racism’ in the first place.”

The post’s emphasis on functionality mimicked the Freedom of Expression policy found in section 1.1.3 of Rights, Rules, and Responsibilities, which states that the University “guarantees all members of the University community the broadest possible latitude to speak, write, listen, challenge, and learn.”

In her email, Calhoun wrote that racial, ethnic, gender, or other slurs in “certain instances” fall under this umbrella of protected speech. She added that community members’ speech would only be curtailed in the case of speech that violates University policy, or “that violates the law, that falsely defames a specific individual, that constitutes a genuine threat or harassment, that unjustifiably invades substantial privacy or confidentiality interests, or that is otherwise directly incompatible with the functioning of the University.”

The email did not specify what conditions would sufficiently impede the University’s functioning to override free speech protections. Asked about this point, Hotchkiss did not offer a comment.

Like Chaffers, Sydney Bebon ’23 disagreed with the University’s response and felt that the University had understated its authority to revise current policies.

“If ‘such language is contrary to Princeton’s commitment to stand for inclusivity against racism,’ then it should be in violation of University policy,” she wrote in a statement to the ‘Prince.’ “This is no longer a debate about free speech in institutions of higher learning but a case of holding a student accountable for a retort involving a racial slur and a personal attack.”

While Chaffers and Bebon criticized what they saw as the University’s inaction, Eddy rebuked the administration for describing his language as “harmful.” The University’s discrimination policies “test our boundaries of free speech,” he told the ‘Prince.’

“We’ve reached a point where we have to be on the cusp of allowing a certain type of racial discrimination to become built into our social animus or our social beliefs,” Eddy said. “Within our own community, we’ve just shifted what’s socially acceptable to right up against what people are able to say determined by their race, and that’s really concerning.”

Calhoun’s message marks only the latest instance of the University grappling to reconcile a welcoming environment for all students, especially those of color, and freedom of expression.

In the spring of 2018, another incident involving the n-word rippled through campus discourse: in his first anthropology lecture of the semester, professor Lawrence Rosen — who is white — posed a hypothetical question containing the n-word to his students. Although the slur immediately incited anger and offense, Rosen repeated it several times, for the sake of what he called a “gut punch.”

Similar to the response in Eddy’s case, students took to social media to express outrage, calling on the University to take action against Rosen.

Both Eisgruber and anthropology department chair Carolyn Rouse defended Rosen, affirming the University’s commitment to free speech even in the face of discomfort or personal alienation.

“When we’re looking at free speech or inclusivity, we have to think hard about what are the right ways to understand those values and how do those values matter to our community,” Eisgruber said at a Council of the Princeton University Community (CPUC) meeting following the incident.

“I think the conflict starts to arise if you believe that what inclusivity demands is some sort of censorship of things that cause people offense or that are important to difficult arguments that need to take place in classrooms,” he added. “I don’t believe that’s the case.”

In their email, Calhoun and the co-signatories acknowledged, “We are now engaged in conversations with a wide range of students and faculty about how to better foster an environment for debate that aligns with our values.”

“We plan to schedule a series of facilitated dialogues for all members of our community who would like to engage constructively on these essential topics,” they continued.

Hotchkiss declined to elaborate on the nature of those dialogues until “plans are confirmed.”