As the summer draws to a close and November nears, public attention has turned to the upcoming presidential and congressional elections. But while the country focuses on the national stage, two Princeton groups are concentrating their attention at the state and local levels.

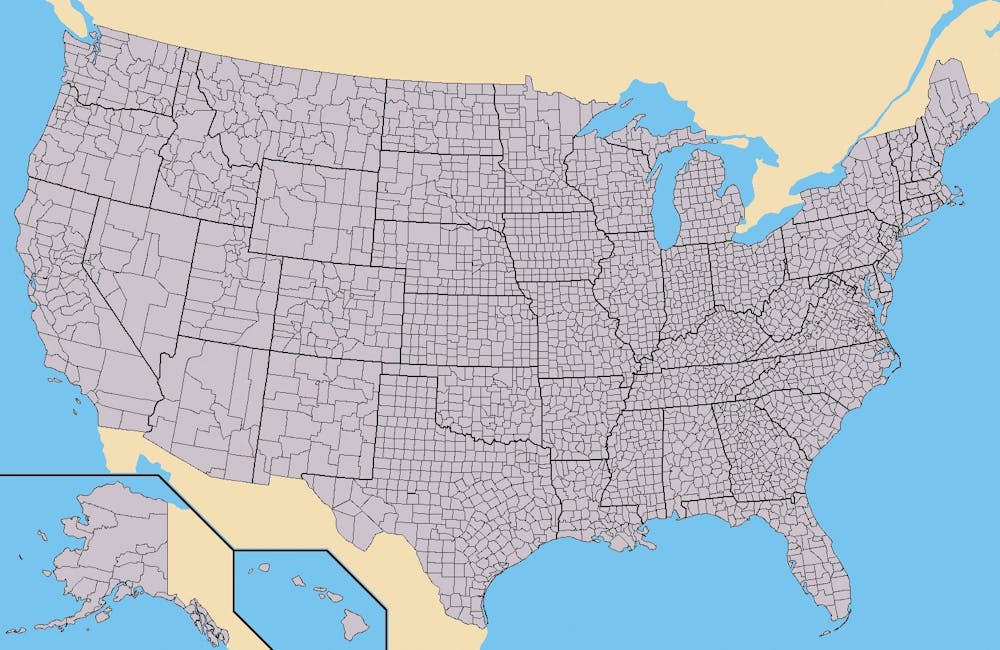

Although the Princeton Gerrymandering Project and Representable use different methods, both teams aim to stop gerrymandering — the practice that allows a political party in control to redraw maps and manipulate election outcomes.

“Gerrymandering, very briefly, is self-dealing in politics,” said Jason Rhode, national coordinator of the Princeton Gerrymandering Project. “What that means is legislators, or whoever is in charge of drawing districts, draw areas in favor of one group of people.”

Rhode continued, “Gerrymandering happens when instead of the voters coming together to pick their representative, an elected representative looks at a map and picks who their future voters are going to be.”

Advocacy against gerrymandering can seem like quibbling over scribbles on a map, but if left unchecked, gerrymandering prolongs racial injustices. According to Rhode, in the 20th century, Jim Crow laws segregated districts by race, a nefarious practice not exclusive to the past.

While this year has seen an increased push to complete the census, the battle for a voice in politics continues long after the forms are mailed. Each decade, politicians use new census results to redraw districts, sometimes gerrymandering in favor of select communities.

The decade-to-decade redrawing of boundaries requires separate interventions for each state; it cannot be solved by an overarching law at the federal level. The two Princeton teams have to remain hyper-vigilant when preventing community underrepresentation.

Though each decade brings a new gerrymandering risk, it also gives advocacy groups a chance to correct previously skewed boundaries. In a battle that rewards the persistent, the Princeton projects have acclimated to the occasional loss, even high stakes ones.

Last June, the Supreme Court ruled that federal courts were powerless to challenge partisan gerrymandering. Samuel Wang, professor of neuroscience and founder of the Princeton Gerrymandering Project, submitted an amicus brief in support of quantitative analysis for detecting gerrymandered districts.

Undaunted, the Princeton Gerrymandering Project has ambitious goals in the near future. For 2021, “we have a dozen priority states to make sure that the redistricting process is better than it has been in the past,” said Hannah Wheelen, the project manager and data coordinator of the Princeton Gerrymandering Project.

The team is also monitoring states with off-year elections such as Virginia and New Jersey, areas whose map-drawing process may stall until 2022 or 2023.

One new project initiative, Redistricting Moneyball, measures state races where voters have the highest leverage. The project follows close races in which the prevention of local gerrymandering leads to state, even national, impact.

Redistricting Moneyball helps the project team find areas where citizens struggle to pass legislation, and where “the only way forward is to direct funds at a close race that might change the way lines are drawn,” said Wheelen.

Although the Princeton Gerrymandering Project prevents and advocates for redistricting through court cases and ballot initiatives, certain problems such as partisan courts are often set up such that “the only thing you can do is try to elect people that won’t gerrymander,” said Jacob Wachspress ’19, a data scientist of Redistricting Moneyball.

The moneyball tool relies on ratings from CNalysis, an election forecaster of state races, and measures the probability of an election change based on one extra vote given to a party in a specific district.

In Minnesota, one of the tool’s study cases, the governor and State House of Representatives are Democratic while the State Senate is Republican.

Neither party controls the redistricting process, but the election for State Senate “looks close,” according to Wachpress. If Republicans lose the State Senate, Democrats will have single-party control of Minnesota’s redistricting.

In Texas, another state monitored by the project, Republicans hold the governorship and both chambers of the legislature. One plausible path to break the single-party control is the Democrats flipping the State House in the 2020 elections.

“Even though it's unlikely, Texas is still coming up as one of our important states to prevent gerrymandering,” Wachspress said. “It's probably the top Democratic target for preventing partisan gerrymandering by Republicans.”

Though the Princeton Gerrymandering Project avoids instructing the public to invest in a particular candidate or political party, the data they provide is publicly available.

“If you invest money and win these elections now, you potentially impact a gerrymandered congressional district for 10 years, whereas if you dump money into the congressional race, you're only guaranteed two years max,” Connor Moffatt, another data scientist of Redistricting Moneyball, said.

Backed and funded by the Princeton Gerrymandering Project and Schmidt Futures, a separate startup in Princeton gathers and supplies a collection of maps to nonprofits.

Representable analyzes crowdsourced data by asking about residents’ community interests, including shared economic backgrounds, social services, and history. Many of the full-time lawyers and data scientists from the Princeton Gerrymandering Project advise Representable on policy and legal affairs.

“We allow states, nonprofits, and different organizations to gather information about organic communities around the United States, as reported by community leaders or citizens,” said co-founder Theodor Marcu ’20.

Created by five students in COS 333, the 1.5-year-old startup recently finished a pilot in Michigan and is soon entering Illinois and Virginia, according to Marcu. The team plans to test the tool in a dozen states, many of which have electoral commissions specially designed to redraw district lines.

“This summer, we are officially launching and trying to scale up our data collection in Michigan because once their commission finalizes at the end of the year, we want to have maps ready as soon as next year,” said Preeti Iyer ’20, another co-founder.

Although the tool works at the community level, the aggregated data has broader implications for the state and national level, according to Iyer.

“We want to hold the people who draw the maps accountable because we're also hoping this data ends up in the hands of journalists, political analysts, and people who have analyzed these maps,” said Iyer.

As hard as project leaders work to create a convenient tool, Representable is also an educational process. The team trains partners in other states to collect accurate and representative data from the community.

Data credibility and security problems, including moderation of content, remain top priorities to ensure “no bad actors and automated robots are messing things up,” Iyer said.

Like many other organizations across political and economic spheres, the Princeton Gerrymandering Project and Representable have adjusted to COVID-19, which delayed the end of census data collection until Sept. 30 and pushed redistricting plans until 2021. In the meantime, both teams urge citizens to fight for representation by filling out the census and questioning their legislators about the redistricting process.

November is near, and time is of the essence for these two groups. Fundamentally, in Marcu’s words, gerrymandering is a “destruction of people’s rights.”