Free speech is a bulwark of American political culture, and University President Christopher Eisgruber ’83’s recent op-ed piece states that it is crucial to Princeton’s culture as well. In its ideal form, free speech is an equalizer.

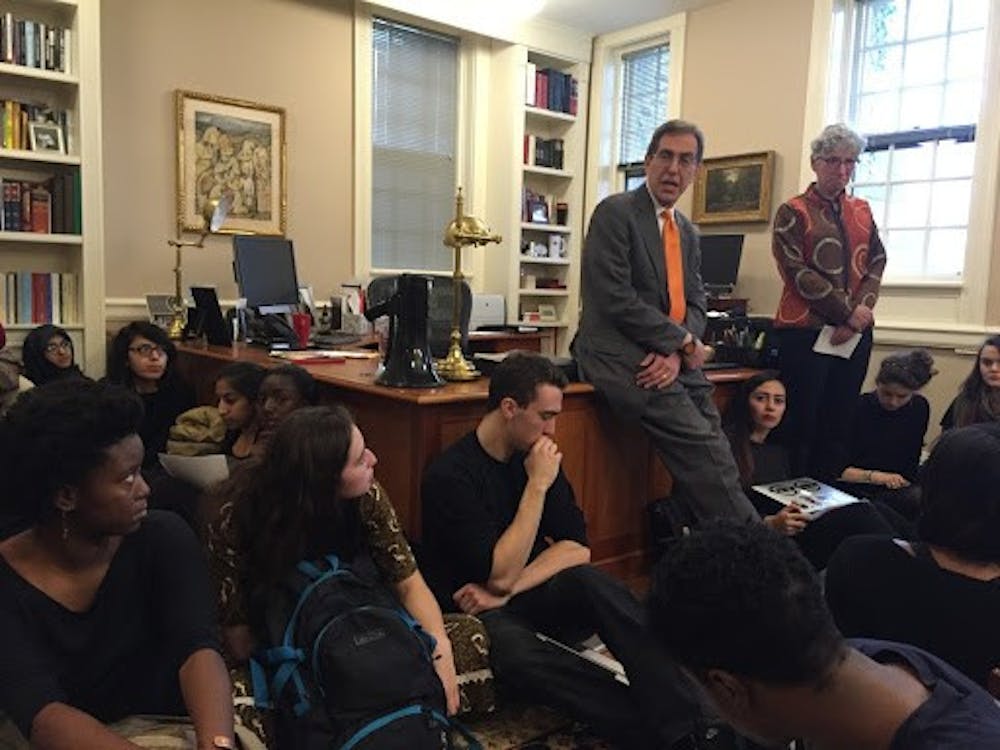

In reality, not all are equally protected when attempting to speak freely. This becomes apparent when examining Eisgruber’s commentary on the Black Justice League and professor Joshua Katz. The former was a group of nonviolent student activists that challenged the ways anti-Black racism manifested on Princeton’s campus and in society at large; the latter is a classics professor who recently penned a “Declaration of Independence” labeling the BJL as “evil” and a “small local terrorist organization.” Eisgruber states that the University’s broad free speech policies “protect Katz’s freedom to say what he did, just as they protected the Black Justice League’s.”

Unfortunately, this is not true. Members of the BJL were threatened with disciplinary consequences, whereas Katz will not face administrative sanction. This microcosm represents the ugly side of free speech: minorities fighting for change are often not protected when exercising it. This is why nonviolent protesters during the American Civil Rights Movement were beaten, hosed, and jailed for marching in the streets. This is why protesters are being met with tear gas at peaceful protests against racism and police brutality across the nation. Pretending that free speech is uniformly protected is inimical to combating racism. It denies a historic and ongoing pattern of silencing the voices of people of color, asserts the right to continue ignoring them, and denies the traumatizing effects of racist speech on those who must endure it.

Counterarguments centered on “academic freedom,” freedom of thought, and freedom of speech have proliferated in response to demands for anti-racist education. They are ultimately grounded in a right to ignore. Exposure to anti-racist perspectives should not be viewed as any different from other academic requirements. As an advocate of anti-racist curricular changes, I hope that anti-racist education would be eye-opening for most and bring about a deeper understanding of how racism continues to shape our society and harm people of color.

However, there would still be room for debate and discussion. Much in the same way a mandated English class couldn’t force someone to interpret literature a certain way, a class about race and power would not tell someone how to think. Rather it would force one to see the world through a different lens. In demanding “freedom” from these difficult discussions, some of our peers and professors are demanding the option to avoid the respectful dialogue that Eisgruber describes as so vital. They are fighting for the right to remain comfortable and continue discrediting the voices of people of color — the right to disengage and center their own understanding in discussions about race.

The conception of freedom of speech as free of racial biases and inherently equal fails to acknowledge the burden that racist speech places on people of color. The “marketplace of ideas” cannot be impartially perused by everyone who enters. Just as different voices are received differently in accordance with their social status, racist remarks are received differently depending on one’s identity. What may merely be a moment to play “devil’s advocate” for a white person can be a traumatic attack on a person of color. Saying that all arguments have merit and deserve evaluation requests that people of color listen quietly when their intelligence, their worth, and their very humanity are questioned. The psychological burden of this is enormous, and the University’s policies have offered no respite so long as attacks are not directed at individuals.

Princeton’s students of color, and Black students in particular, are being forced to endure the same remarks over and over again in the name of free speech, both inside and outside of University channels. This is incongruous with the University’s recent pledge of anti-racism. If the University has accepted that racism exists, that it is a systemic force that drives the murder and oppression of Black and Brown people, and that racism needs to be fought, then why are racist beliefs still being entertained? Why must students of color face the emotional toll of “proving” that they deserve respect and a place on Princeton’s campus? What is so “enriching” and so “academic” about protecting speech that clearly causes harm?

It cannot be denied that conversations about race are difficult. However, to promote “free speech” as a key part of the solution fails to acknowledge that the concept is heavily racialized. Anyone can speak, but minorities advocating for change have historically been ignored and met with violent backlash from dominant groups. When people of color attempt to speak freely, they are often degraded, ignored, and attacked. A true commitment to anti-racism will mandate much more effort and action on the part of the University to address the complex and far-reaching impacts of racism. First and foremost, though, it will require that the University community actually listens to and respects the myriad perspectives of its students, faculty, and staff of color.

Brittani Telfair is a junior concentrating in public and international affairs from Richmond, Va. She can be reached at btelfair@princeton.edu.