In “photúalma,” artist Lauren Olson ’22 examines confinement, family, identity, and history through a series of short films and podcasts. Her films feature audio clips ranging from conversations in an art history class at Princeton to Olson rapping along with Kendrick Lamar in “Money Trees.” Slides of her photographs, most of which she shot in her brother’s music studio at home in Ohio, phase on- and off-screen in a kaleidoscope of vibrant reds, oranges, and blues. When I first watched Olson’s work, I was intrigued by her raw authenticity to self, evident in details such as the unedited footage of her photos in Adobe Bridge at the beginning of “33.” The third video installment of photúalma, “SIN.ME,” feels particularly candid, with fragments of Olson’s process behind the camera and an intimate look at the private, eccentric moments of everyday life that often pass by unrecorded.

In my conversation with Olson, we discuss the motivations behind her work, which really means exploring confidence, authenticity, light-dark dichotomies, and spirituality — concepts essential to understanding the human experience.

Olson’s current project has five parts, all of which can be found on her YouTube channel.

Cammie Lee: Could you tell me a little bit about the project you’re currently working on and your process as an artist? If you want to focus on a specific film, that’s also fine.

Lauren Olson: I guess I’ll just start by kind of explaining how this project came about. So … I am a visual arts student. I declared my major super late because I didn’t really know what I wanted to do, but fell in love with photography in the fall of this year. I took another class in the spring and I was like, “okay I know this sounds really ridiculous,“ and everyone asked me, “what are you going to do with a visual arts major?” But this is what I love, so this is what I’m going to do.

Then this summer I got the Dale award. My proposal was to go do an exploration of self and family and identity in Colombia, South America, which is where my mom is from, and then I was going to bring my camera along and do a whole photo project about it. But obviously because of COVID-19, plans got altered, and I decided I was just going to do a project from home exploring a similar concept, but obviously through a much different lens, because I’m in Ohio, not in Colombia.

That was the plan going into the summer. I’ve been mulling this over in my head and thinking like, what do I want to do, what do I want to do, and I started to kind of feel paralyzed throughout the summer until last week. I barely picked up the camera. I felt kind of weird — I didn’t know how to explore this big of a topic in such a confined space. I wanted to say so much, but I didn’t know how to do that. And then two weeks ago I just kind of picked up my camera and I was working with my [brother] — he does some studio production, so I was sitting in the studio with him and just experimenting with some stuff, and I realized, I had been putting this off, and all I want to do is take pictures and explode. I just want to expose so much of what I’ve been thinking, and everything that’s going on for me, and like, that’s a huge project. How do you tell someone in a piece of art, this is literally all of me? How do you get that out? So this project is just like — I want all of me in an artistic experience. Which is a huge goal and really bold, and kind of risky, and kind of scary, because I’m really exposing myself here. So hopefully people like it, fingers crossed, but I guess that’s kind of the impetus for the project.

It just explores a lot of aspects of my life, which I think makes it relatable to a lot of people. For example in the first one, I used a lot of audio clips from classes I’ve been in, and things that I’ve thought about just from being at Princeton. It definitely explores concepts of diasporic identity, which I didn’t really think about super deeply until I got to Princeton, or just thinking about art in an academic sense. For me that’s very much a Princeton experience — I got that from Princeton, and it’s fueled my art to be something much more than it could’ve been before I had that. This is why my art exploded, because I was at Princeton and I was able to think about these things, and talk to these profs, and be in these [Gender and Sexuality Studies] classes. Like — gender theory, what is that? And now my art is exploring things like that.

But as this series progresses, I want to get into the less intellectual part of who I am, and get into the deeper, really exposed, raw parts of who I am, and just keep exploding from there, and just keep going deeper and deeper and deeper and deeper, and hopefully attract some viewers along the way. My ultimate goal would be for someone to see the progression of this, and be inspired to be naked, because I feel like through doing this I’m kind of — this is a metaphor obviously, I’m not walking around naked — taking off my clothes. At the end of this I want to be able to walk around every single day and feel like I’m not ashamed of a thought I’m having, I’m not ashamed of a feeling I’m having, I’m not ashamed of what I’m wearing, I’m not ashamed of anything, I just know myself, I feel myself, and I’m comfortable being in the world, existing that way. I think that creation from that space, of being really okay with yourself, and being able to express yourself however you want, is the most powerful kind of creation. The best artists are able to produce such powerful stuff, because there are no restrictions inside. There’s no conflict — it’s just kind of flowing through them.

CL: What you’re saying about confidence and exploring that in everyday life, and learning how to inhabit a headspace that allows you to be yourself authentically really resonates with me, and it’s something that I’ve been thinking about a lot. I’m wondering for you, when you’re creating, what does it feel like to enter that space, and how do you hope to develop the strength to inhabit that space at all moments of your life?

LO: I think that’s been a huge exploration for me, this whole confidence thing. At the end of the day, the thing that holds me and anybody else back is that balance of being confident. If you believe something to the core of who you are — but getting to that point is definitely really hard. I’ve started to get that feeling bleeding into my life more, although it’s definitely easier to focus that and channel that when I’m creating versus when I’m just doing regular things. I’ve noticed recently when I’m having a conversation with someone or doing something that’s not art, it’s kind of easy for me to slip into self doubt, which is really interesting for me because I don’t want to have to be making art all the time to feel confident. I want to be able to be confident even if I’m not sitting at my desk editing a video or taking photographs.

The best way I can explain how I get to that space is through a section in my third video, where there’s a scene, and then there’s a part where there’s a black screen, and I’m just talking, kind of to myself, and I’m just amping myself up and it’s kind of hilarious. I’m just sitting there, and I’m like, “this is fucking awesome.” It’s almost like how athletes get before a race, where you just kind of go crazy. It’s not cocky; it’s just hyping yourself up. It’s really fun and energizing. I use that during art, and when I’m having a moment when I’m worrying, “is this right?” or “how are people going to look at this?” No, no, no, no. Just go back to that moment when you were like, this is awesome and this is you, and just hold on to that. I try to hold on to that as much as possible when I move in and out of different spaces.

Doubt just tends to seep in. It’s a natural human response. One thing I’ve thought about too recently is that doubt is super important because it teaches you how to get to those moments of confidence. You know if you’re in a state of doubt. It gives you a check-in, and allows you to go back to the other phase. The polarity almost needs to exist for you to be confident. Doubt is also important in confidence. I think that looking at everything in terms of “good” and “bad” is dangerous, so I try to use it as a gauge. What could I be doing better now, or how can I get back to that state?

CL: I was reading something, that in our society, in the movies and a lot of the media we consume, there’s a tendency — especially in mainstream superhero movies and cartoons — to teach kids that there always needs to be a bad guy, and that there’s always a good guy, and that these two characters exist as total opposites. I’ve been thinking that because of the way we grow up learning about the good and the bad, it becomes a lot more difficult for us to empathize with the opposite of what we believe. We impose our moral center of gravity on others. I think that’s becoming so evident, especially now on social media. It breeds this culture of not trying to understand people as human beings, but just evaluating another person within that dichotomy of good and evil.

LO: That’s definitely something I’ve been grappling with a lot this year, in school, in my head, in this project. This idea that it has to be one or the other — you just feel so split, you feel so fragmented. Why can’t we accept that they’re both necessary in everything? I think for me, two of the biggest things are masculine and feminine. I’ve really struggled with balancing those two forces. Masculinity seems like this thing I’m supposed to avoid, and also this thing that I’m not allowed to be, and it’s caused a lot of internal conflict to try to figure out what’s going on here.

You were also talking about morals. I think that’s super important — nothing is strictly good or bad, nothing can purely be one or the other. For lightness to exist, darkness has to exist. You cannot have one without the other, because their existence necessitates both. So if that’s the case, then it’s too simplistic to say that this thing is just good and this thing is just bad. It’s so much more complicated than that. I think life is infinitely complex, and to call something good or bad or light or dark or masculine or feminine strictly — I think that limits growth.

A lot of times, at least for me, the “negative” experiences in life are the ones that I get transformed by the most. I went through a dark time in high school, was super depressed. I’ve never been in that headspace before, and when I was in it I was like, “this sucks. Life is shitty,“ but looking back, after that experience is when I started to become who I am right now, so it was necessary to who I am. Yes it was a negative experience, but had I not had it, I wouldn’t be here now.

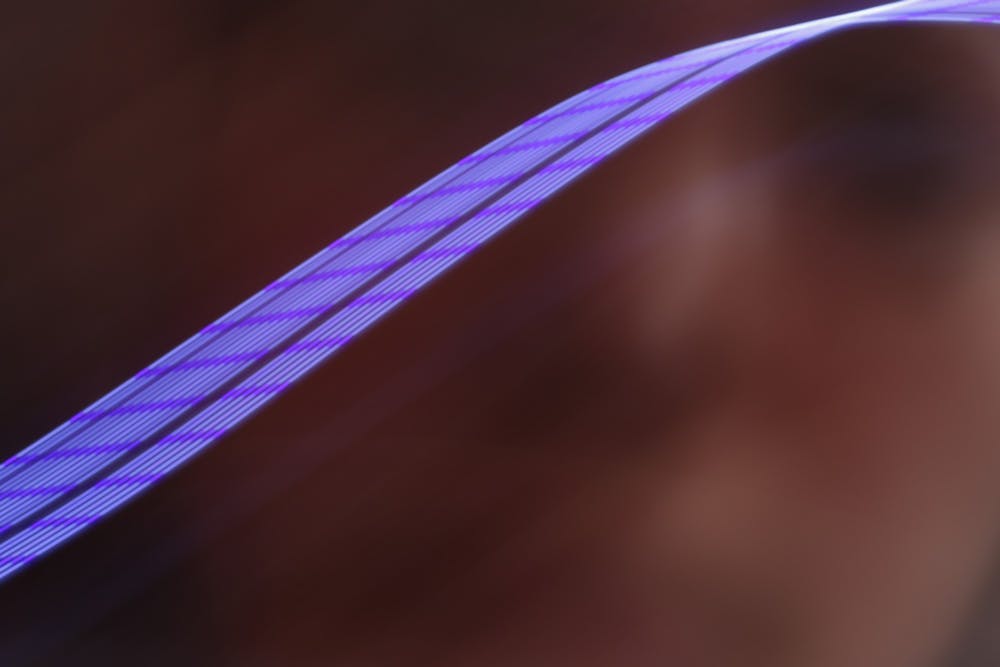

CL: Our conversation about light and dark reminds me — I wanted to ask about the images in your film. I noticed that in the first one, you created these really interesting light sculptures, and I liked how the forms of them seemed to imitate the sculpture you were talking about by Yinka Shonibare. Could you tell me about your decision to create those images, and what that was like?

LO: That was actually sort of an accident. My brother had LED lights in his studio that go around the rim of the room, and it was dark so I had my camera on a long exposure, which just means that the shutter is open for a long time, so any movement it’ll detect. I was moving my camera around, and when I looked at the image it was this crazy wave kind of thing, and I was like, ‘Oh that’s kind of cool.’ So I started playing with that a lot, and I’ve actually been playing with that more and more because I can make this more complex the longer I keep the exposure and the more specific[ally] I move ... the colors of the lights.

I always had this idea that the universe is made out of this energetic fabric, and it looks like a sheet and everything is made of these lights, and we just can’t see it because our eyes are not powerful enough. Like when you see those images in the intro of shows about space, where there’ll be a planet, and there’s this fabric coming in, and they try to depict space time. I think of everything being made of that energetic cloth, and I’m trying to create that visually. I want people to see that this is actually what things look like, this physical form is kind of an illusion in a sense … I wanted to introduce this new way of seeing something physical as something that you can still perceive, but don’t really know what it is.

CL: I like that idea of trying to depict something that words can’t quite accurately capture. I’ve been thinking a lot about spirituality, and what or who God really is. I like this idea, sort of like what you were talking about, of a life force that connects all living creatures, and that connects us to the trees. I’ve been reading Michael Pollan’s book “How to Change your Mind,“ and he talks about how these scientists who research psychedelics truly believe that psychoactive mushrooms are trying to tell us something about the fabric of life. I like how you expanded this concept to also capture space beyond just our existence on Earth, because I think as humans, we tend to have this self-centered perspective.

LO: Yeah … I fully believe what you’re reading. I actually haven’t done psychedelics yet, but based on the experiences I’ve had, I really think that the natural things that grow on this planet — whether that’s plants, like marijuana, or mushrooms — if we weren’t supposed to experience that, why would it exist in nature? And so why deny the truth of that experience? If you’re having this trip and you’re seeing this energetic field, and you’re seeing auras, and you’re in space on another planet — I understand that sounds crazy, but if the Earth is providing you with that experience, I don’t know how quick we should be to just say “that’s not real.” It might not be real in the way we think it’s real, but discounting that right off the bat is a little bit unfair. I feel like we should give that stuff the benefit of the doubt and explore this fabric of existence — what does that mean? I feel like that’s worth asking, and something that I’m trying to pose as a question to people through this work through these abstracted fabrics.

CL: Another thing I wanted to ask you about — I read the description of your video as well, and you mentioned that this film captures your experience as an Ivy League student, and I was wondering if you could say more to that, and how you tried to depict that with visuals or audio in your films.

LO: Well first of all, I used Ivy League instead of Princeton just to make it something that people from an intellectual liberal arts college could relate to. It’s not that I was trying to avoid the Princeton title, but I just wanted to make it something bigger than just the Princeton community. That was for the first video, and in that film there was definitely a lot of grappling with a lot of the intellectual things that have been planted in my mind, like this explosion of understanding. It’s kind of this push and pull between logic, and also wanting to break away from this strictly logical framework of things.

The whole video is kind of like you’re on this weird trip where everything is flashing and moving, and for me, that’s kind of how my experience at an Ivy League [school] feels like. It’s very much enlightening and it feels like my head’s on fire and I’m seeing the world, but at the same time, the more you learn the more you question, and the more you’re not really sure, so it’s kind of this experience of uncovering knowledge, almost to keep putting you further and further into this state where you’re like, “I don’t even know what’s true anymore.” It’s just a trip, really.

Just keep paying attention to the descriptions. I’m definitely trying to build a persona throughout this project. That’s just kind of the fun of it. I mean, Kanye wouldn’t be Kanye without the Kanye persona. Not that I’m trying to be Kanye — I know that’s a very controversial thing to say — but I think the performance of it is really important. The video would be totally different if I said, “My mom died last night.” Playing with the installation of my videos is a critical component, and one that I’m very focused on to help light the spark I want to start online.

CL: In a similar vein, I wanted to ask you about the digits you include between letters and the spacing between characters. In particular, I was wondering why you chose the number nine. I noticed in the title of your second video, you included nine threes. Was that just a coincidence?

LO: So I will tell you: everything I’ve done up to this point is extremely intentional. There is not a shot that I’ve put in, a soundbite I’ve put in, a letter or a word or a punctuation or a post that I put on Instagram and take down — everything I’m doing is for a very specific reason. The point of that isn’t necessarily for you to figure out the reason, although I invite you to try to because I think that’s part of the fun, but the point is that none of this is a joke, none of this is just me going out on a whim. I specifically count — one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, before I put out that video. So what you’re doing — picking up on those pieces and figuring out the details, is exactly what I want people to be doing. Eventually, when this comes full circle, you’re going to have a lot more answers by paying attention to the details. What I’m doing is intentional. That’s the biggest thing I can say addressing your questions about that.

I really appreciate your attention to detail, and I hope people continue to pick up on that too. What I really love about art and creation is it forces people to consume thoughtfully, instead of just flipping through something quickly and moving on. In the age of the Internet, we’re overwhelmed with so much data, and I think it’s so important now more than ever to really protect art and the way it makes space for truly indulging in something instead of just trying to consume as much as you can, as quickly as you can.

I think as this progresses, these are going to become less intellectual and more experiential, but at the beginning I think it’s important to get the message out that this is something worth thinking about beyond just being purely an aesthetic experience. I think aesthetic experiences are awesome, and they move people, and it’s something that needs to continue on past the viewing and lingering in your mind and change the way you think about things, because that’s the only way you can change people. If you can alter the way they think about the world and how they feel, then you can’t alter the world. But you have to get the mind and the heart. You can’t just get one because then it doesn’t work.

I have things ready to go to release, but I just want to make sure that people are watching before I do it. I have things that I think will resonate with people in the heart, but before that happens I think they need to get a grasp for what I’m trying to do or else it won’t have the impact that it could have. It’s really important to me — this message of showing my authentic self, and showing people this process of undressing. I want people to watch — not in a look at me sort of way, because this is actually really scary and like, why would you want to stand outside and have people watch you get naked? I just want to show them this experience because this is something that can happen. My motive is that I love everyone, and that’s a hard thing for people to hear, they’re going to think that’s just cliche and weird, but it’s really an act of love.

…

Before I started posting these videos, I couldn’t text anybody back from school. I was totally isolating myself. I would get a text like, “Hey let’s talk,“ and it would be two weeks before I would answer. I was kind of in a hole and I was like, this is stupid, I’m not connecting, I’m sitting in my bedroom, and yeah my family doesn’t get me, and it felt like I was super disconnected. But as soon as I started putting something out there, making something, I’ve had people that I don’t even know message me and they’re like, “Hey can you read my poetry,” or “Hey I make art too,” and I’m having all these conversations with people.

There’s this lifeguard at the YMCA that I used to see all the time, and yesterday we had this 30 minute conversation about spirituality, and who knew! It just felt like all these things are clicking into place, and it’s crazy! I’ve been sitting on this the whole time. I see this kid at the Y, I go swim at the Y a lot because I used to swim competitively, and I see him three, four times a week, and yesterday was the first time we’d had that conversation. I can’t say I can have that conversation with everybody, but when you start opening yourself up to it, it starts coming to you. By focusing inward, it also goes outward, so it’s a fluidity of the internal and the external just flowing together. It’s just hard to ignite that thing that makes you get back into motion.

Lauren Olson ’22 is a student in the Program in Visual Arts. She can be found on Instagram or contacted at lo5@princeton.edu.