For the first installment of this two-part series, click here.

“Removing Woodrow Wilson’s name was not our first demand. It was not our fourth demand,” Joanna Anyanwu ’15 GS told the ‘Prince.’

Wilson was not at the core of the BJL’s early campaigns. But in the fall of 2015, the call to remove his name commanded national attention, largely eclipsing the BJL’s other goals.

On Sept. 14, 2015, at an undergraduate conference titled “Ferguson is the Future: Speculative Arts + Social Justice,” Destiny Crockett ’17 and fellow BJL member Wilglory Tanjong ’18 presented on Wilson’s racism. They projected quotes from Wilson to demonstrate how he idolized the Ku Klux Klan, resegregated the federal workforce, and advocated for white supremacy.

Such words could not be excused, even for a man “of his time,” the students argued. To the BJL, for such a man to be honored and blindly praised — including the use of his likeness to be as symbolic of Princeton as its tiger mascot — was unacceptable.

BJL members distributed posters that laid bare Woodrow Wilson’s racism.

Courtesy of University Press Club, 2015, and Destiny Crockett

In October 2015 BJL members placed posters of Wilson’s words, overlaid on his portrait, across campus. History and African American studies professor Joshua Guild recalled the postering campaign as “an incredible intervention.” He noted that, at the time, Wilson’s white supremacy was not widely known. The posters shocked most students, who likely “had not heard any of this before.”

“It made anyone who saw those posters have to confront that this is a different Wilson,” said Guild. “This is not Wilson from the League of Nations. This is not Wilson the inventor of the precept. This was Wilson in his own words.”

‘Birth of a Nation’ projected on Frist Campus Center.

Courtesy of University Press Club, 2015

As President of the United States, Wilson held a White House screening of “Birth of a Nation,” a 1915 film widely credited as a catalyst in the Ku Klux Klan’s resurgence.

On the night of Oct. 9, 2015, the BJL projected “Birth of a Nation” on the southern wall of Frist Campus Center, and again, on the columns of Robertson Hall, home of the then-Woodrow Wilson School.

Next to the screenings, they placed posters that read, “Wilson said of the film, ‘It is like writing history with lightning, and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.’”

They wanted students, faculty, administrators, and others to confront Wilson’s racist legacy — and to challenge his lionized presence on campus.

‘We are not asking, we are demanding’: Occupy Nassau

Nov. 18 saw a wave of national student protests: #StudentBlackOut demonstrations cropped up on campuses across the country, including at the University of Missouri, Tufts, and Yale.

Crockett recalled that activists from over 20 colleges and universities had vowed to “do something bigger than anything we had ever done before.”

Flyers publicizing the Nov. 18 protest characterized it as a “WALKOUT,” with no mention of the planned sit-in. The BJL did not want to alert the University that they intended to enter Nassau Hall.

At first, only a few students seemed to take part. On their live-blog, the University Press Club described the walk-out as a “trickle.”

Yet once around 200 students had reached the Nassau steps, their presence became undeniable. As they walked into the building, protesters chanted, “Who built this place?” A chorus replied: “We built it!”

The crowd flooded Eisgruber’s office, overflowing into the atrium.

“It was technically his Office Hours,” Crockett said.

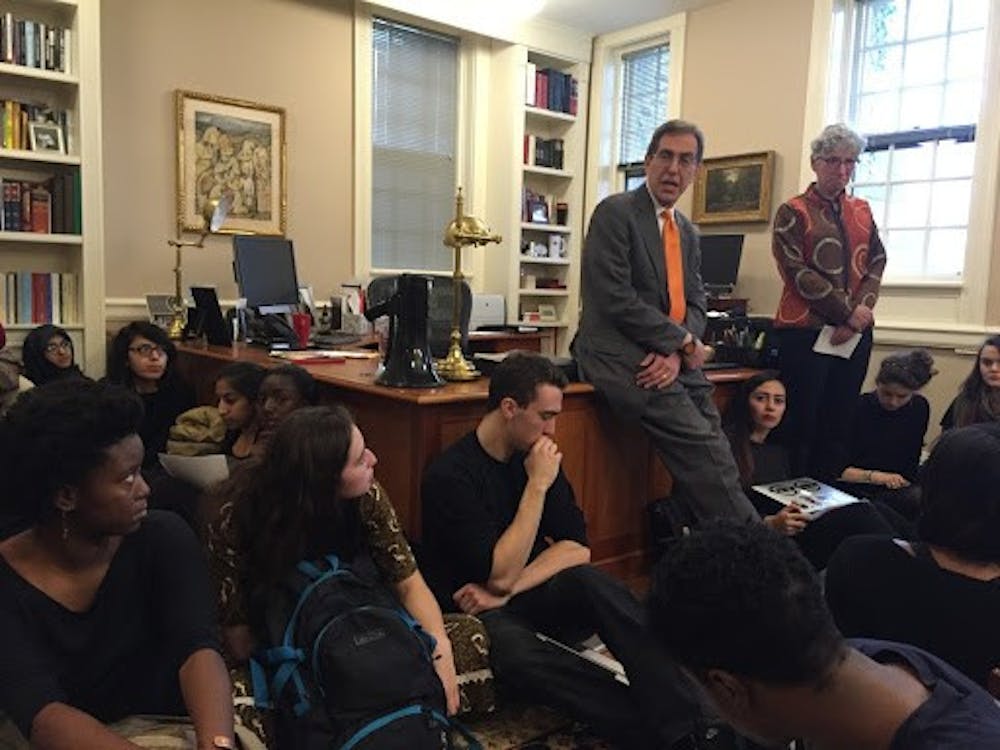

Around noon, Eisgruber came into his office and began to speak with the protestors. Leaning against his desk, he addressed the students, who sat on the floor around his meeting table, surrounding his feet.

Kupupika recalled feeling dissatisfied with the conversation. According to her, Eisgruber questioned what could be “properly defined as racist,” especially with regard to mandatory cultural competency training, which he viewed as “neither feasible nor effective,” according to the ‘Prince’ at the time.

Students in President Eisgruber’s office on Nov. 18, 2015.

Courtesy of University Press Club live-blog, 2015

Eisgruber likewise resisted demands for Black affinity spaces and housing. As quoted in the ‘Prince’ at the time, he said, “We can’t do this for Black students and not also for, for example, students from Latinx [sic].” The ‘Prince’ further reported that although he agreed with adding a distribution requirement dedicated to the history of marginalized groups, he said he lacked the authority to implement it.

According to the UPC live-blog, Dean of the College Jill Dolan also joined the conversation, saying that administrators were already considering the distribution requirement. She warned, however, “These institutions are old. They don’t move as fast as anyone would like.”

As for the removal of Wilson’s name, according to the UPC live-blog, Eisgruber “[agreed] that Woodrow Wilson was a racist” and that his legacy should be examined, but did not agree that his name ought to be removed, as “human beings have good and evil in them, and Wilson is one of those human beings.”

The ‘Prince’ reported that on the first day of the sit-in, Eisgruber “said that he had no plans to sign the document outlining the demands of student protesters.”

“We are not asking, we are demanding,” Crockett said, according to the live-blog. “We’ll be here. Ruha Benjamin has ordered us lunch.”

Benjamin, the African American studies professor who had spoken at the Chapel, did not respond to a request to be interviewed for this story.

At around 1 p.m., Eisgruber and Dolan left the office and the doors of Nassau Hall were locked. They could only be opened from the inside.

Though student protesters wished to talk further with Eisgruber, for the time being, they held their ground. They rallied their spirits with chants, sang along to “Alright” by Kendrick Lamar, and read aloud speeches by Malcolm X.

“This is our black space until further notice,” one student said to the UPC.

As the protest garnered attention on campus and across the nation, the protestors garnered both support and backlash.

“I was doing a lot of documentation on Twitter,” says Anyanwu. “We got Woodrow Wilson to trend nationally. People called me a n****r, made death threats.”

On the University’s Facebook page, various users left over a hundred comments that criticized, insulted, and threatened BJL members. Commenters accused protesters of trying to segregate the school and erase history, calling them “crybabies,” “Stalinists,” “terrorists,” and demanding their expulsion, arrest, and murder.

“[Take] up the call to duty and arm yourself and protect your school from these invading hordes of spoiled shits,” one comment read, according to a screenshot provided by Anyanwu. “Two shots in the head and two in the chest for each of them should rectify the situation and quiet the storm of stupidity.” The comment is no longer available online.

On YikYak, the most popular posts sided with Eisgruber and the University. “#EisgruberMatters,” one post read, in a parody of the phrase Black Lives Matter.

“I’m so disappointed that Princeton students followed suit by leading screaming, disrespectful, angry protests,” read another.

“The hate was real, of course,” Kupupika said, noting that she nearly declined to be interviewed for this piece because of what she saw as bias and “lack of journalistic integrity” that the ‘Prince’ demonstrated against the BJL.

A number of other BJL alumni declined to be interviewed for this story, citing similar reasons.

Kupipika said that one student sat with protesters in Eisgruber’s office, not to support the BJL, but rather to collect inflammatory quotes for a critical op-ed, later published in the ‘Prince.’ The author did not identify herself as a reporter, Kupupika alleged, and the quotes were printed without the students’ consent.

The op-ed’s author did not respond to request for comment.

Furthermore, the ‘Prince’ Editorial Board condemned the BJL’s demands, arguing that “[Wilson’s] abhorrent views and acts do not erase his significant contributions.”

Board members were divided on the distribution requirement — some were in favor, while others proposed a “Global Thought” requirement instead, as they did not “believe administrators should be in the business of determining which groups of people are or have been marginalized.”

One Board member wrote that such a requirement would be “nothing more than a cover for mandating courses in the hyper-politically-correct ‘studies’ departments.”

Several other board members recused themselves or dissented from the editorial.

The members of the 2015 ‘Prince’ Editorial Board either declined or did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Despite the resistance that the BJL faced, Kupupika recalled the far-reaching community that emerged during the sit-in.

“A lot of this was framed as ‘The BJL,’ but we were a small group of students,” Kupupika said. “When there is a movement or a moment, people want to focus on like, who was in the civil rights movement, who was in the Black Panther Party. But it’s also like, community uplifted us by bringing us food and water, praying with us, crying with us.”

Anyanwu and Crockett likewise recalled fondly the many students who stood outside Nassau Hall in solidarity with those sitting within, and the faculty members who showed support, including Professor Eddie Glaude GS ’97, chair of the African American Studies Department.

Among other allies was Reverend William Barber of the Poor People’s Campaign and the Moral Mondays Movement, who came to Eisgruber’s office after delivering a lecture at the Chapel.

“Hold your stance,” Barber told the students, according to the live-blog.

At the request of his students, a third of whom were participating in the protest, Guild held his 2 p.m. precept for HIS 387, African American History from Reconstruction to the Present, in Nassau Hall. Surrounded by the student protestors, Guild conducted precept on the atrium’s floor, as his students discussed the sit-ins of the Civil Rights era.

Guild asked the protesters how else he could show support, Crockett remembered. She asked for smoothies, and eventually a pizza dinner arrived.

“I didn’t personally buy the pizzas,” Guild said, “I think that was Professor Benjamin.”

But as more and more community members — even some “middle-aged townies,” per Crockett — decided to show their support, the dinner expanded. It soon featured a wide selection — from Qdoba to Indian food, cookies, and, of course, pizza — lots and lots of pizza.

Dinner in Nassau Hall during the BJL’s protest.

Courtesy of University Press Club live-blog

As the official closing time of Nassau Hall, 5:30 p.m., approached, students began to consider spending the night.

“People who were in the office were informed that if they were to leave, then PSafe would not allow them to return the next day,” Kupupika said.

“Someone brought sleeping bags, toothbrushes, toothpaste and deodorant,” Crockett said. Outdoor protesters began to set up tents, preparing for rain.

At 5:15 p.m., Dean of Undergraduate Students Kathleen Deignan came to Eisgruber’s office with a warning to student protesters.

“You should anticipate that there could be disciplinary consequences when students occupy private space,” she said, according to the UPC live-blog. “No one can remain in the building after the building closes. If you do not leave, then the University will have ODUS staff and Public Safety staff here in the building, but that does not mean that you will not be in violation of University regulations.”

Anyanwu and Crockett, who were in the room at the time, told the ‘Prince’ they feared expulsion and weighed whether they should leave. As a graduate student, Anyanwu called an administrator in her program, Scholars in the Nation’s Service (SINSI). Anyanwu remembers being told that she was “in a more precarious situation, since people are more forgiving of undergraduates.”

She called her mother, whose advice was straightforward: “Don’t get expelled.”

Crockett stayed in the office, but Anyanwu decided to sleep outside.

Later that night, according to the live-blog, Glaude returned to speak with the students.

“You started the action and there are some consequences that you are immediately confronting,” he said. “The question is whether at this stage in the game you are ready to face the consequences.”

Rev. Barber returned to lead an evening prayer.

“Y’all are serious, aren’t you?” he asked, according to the live-blog. “I have to fly back tonight but you students are making me want to stay.”

The next visitor was Ruth Simmons, then a University Trustee and former President of Brown University. Simmons, now the president of Prairie View A&M University, a historically Black college, told protesters how she would burst into tears as she tried to describe the experience of Black students to non-Black Trustees.

Outdoors, students sang and chanted. Many, including Kupupika, marched down campus to the residential college that bore Wilson’s name. Others stayed outside Nassau Hall, so that they could be heard by those sitting in. “Amazing Grace” and “We Shall Overcome” rose from the lawn, carrying sit-in protesters through the night.

“We won’t tolerate hate,” students chanted. “We here. We been here. We ain’t leavin. We are loved.”

Waking up in Nassau Hall on the morning of Nov. 19.

Courtesy of University Press Club live-blog

The next morning, the rain stopped, the sun rose, and students awoke after a night spent on atrium tile, office carpet, and the ground outside.

Crockett recalled receiving a phone call from an unfamiliar number. The voice on the line, which addressed her as “Sister Destiny,” belonged to Professor Emeritus Cornel West GS ’80. He spoke to sit-in protesters over speakerphone, asking what he could do to help.

West agreed to organize a faculty letter endorsing the protests and, soon afterwards, posted on Facebook calling for students who took part in the protest to be granted amnesty.

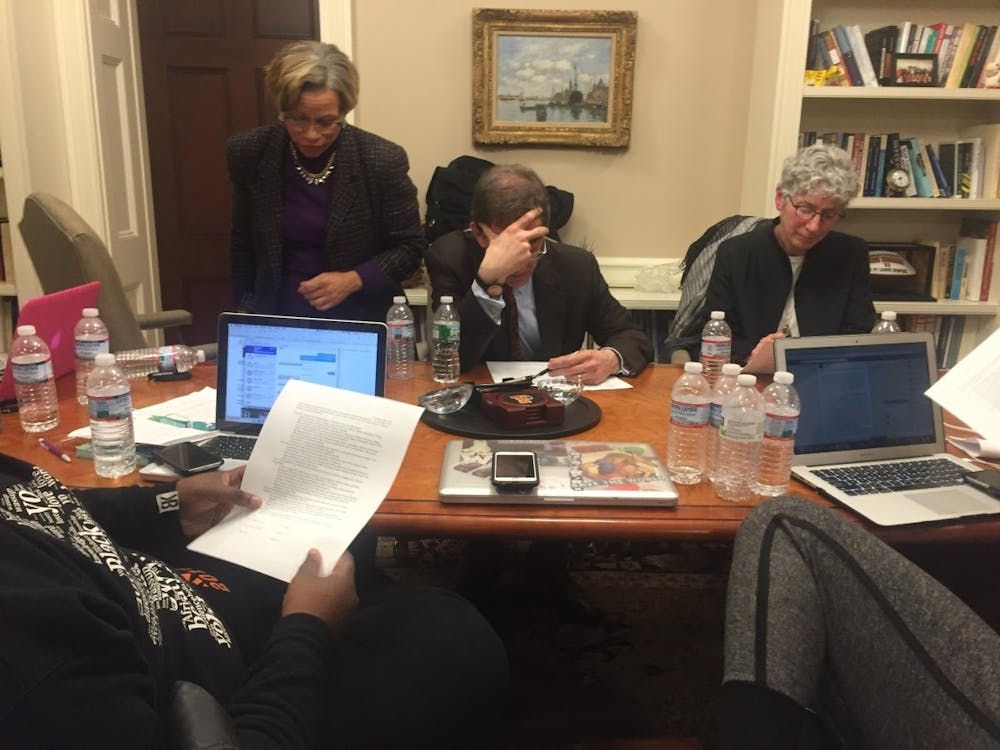

By 2 p.m., Eisgruber, Dolan, and other administrators agreed to meet the sit-in protesters, either in Eisgruber’s office, without protest leaders who were locked out, or in a separate conference room with all protest leaders in attendance.

The sit-in students held their ground. Administrators caved, allowing the protest leaders outside to join negotiations in the President’s office.

What came next was a six-hour back-and-forth.

Eisgruber agreed that a photographic mural of Wilson in the residential dining hall should be removed, according to the live-blog. He added that the University ought to reckon with the “complexity” of Wilson’s legacy, and Dolan agreed to consider affinity housing as “part of the conversation.”

Administrators still questioned the efficacy of mandatory diversity training, believing it would be both ineffective and unpopular.

“The hardest thing that we can do is have the faculty vote on mandatory training for themselves, that’s like asking them to tax themselves,” Eisgruber said, according to the live-blog.

Dolan said the General Education Task Force was already considering the distribution requirement, and that the BJL was welcome to attend their meeting on the subject.

Lastly, the students demanded amnesty for protesters, pointing to threats of disciplinary action from the day before. The live-blog quoted Vice President for Campus Life Rochelle Calhoun, who described such warnings as “routine” — “not unique or particular to this event.”

“No formal disciplinary action has begun, nor will it begin, if you leave the building,” Calhoun told the protesters.

Students continued to pressure the administration to provide more concrete commitments to their demands. As Eisgruber maintained that many of their demands fell beyond his authority, protesters asked him what he could do. Dolan assured them that change happens, but “little by little.” Students, in turn, criticized such incrementalism as an excuse.

President Eisgruber, Dean Dolan, and VP Calhoun discuss demands with protestors.

Courtesy of University Press Club live-blog

Once again, it was almost nighttime, with no resolution in sight. Protestors and administrators began to draft a revised sheet of demands for University representatives to sign. As the discussion reached an impasse, chants from the atrium resonated in the office.

“No Justice, No Peace.”

Students both within and outside of Nassau Hall prepared their makeshift beds for a second night’s sleep.

In the office, there was controversy over specific wording, according to the live-blog. In particular, contention arose around the sentence, “The board of trustees will collect information on the campus community’s opinion on Woodrow Wilson School name and then make a decision regarding the removal of the name.”

The live--blog reported that Eisgruber had said he would withhold his signature until “regarding the removal of” was replaced with “on.”

The protesters conceded. A printer whirred. A fresh document of revised demands was passed around, and finally, signed.

“We appreciate the willingness of the students to work with us to find a way forward for them, for us and for our community,” Eisgruber said, following the sit-in. “We were able to assure them that their concerns would be raised and considered through appropriate processes.”

At 8:45 p.m., Nov. 19, sit-in protesters stepped outside of Nassau Hall for the first time in 33 hours. The sit-in was over, and they felt real change was in the air.

‘A complex legacy’: the sit-in’s aftermath

The victory was short-lived. At 9:05 p.m., as sit-in protesters were walking back to their dorms, they learned that a bomb and firearm threat had been made on Nassau Hall, making specific reference to the sit-in.

At first, for Crockett, the threats didn’t register as a serious matter. But when she made it back to her room and found that a note had been slipped under her door, she realized just how easy it was to find where students lived on campus. The note, although an expression of encouragement from a sympathetic classmate, left Crockett with a heightened awareness of her vulnerability.

As nervousness turned to fear, Crockett reached out to West and African American studies professor Imani Perry to ask if they could help arrange accommodations off campus.

Her faculty confidants first advised her to ask University administrators about what they could do. Crockett contacted Calhoun who, according to Crockett, told her that she need not be concerned.

Crockett then returned to Professors Perry and West. That night, several BJL protesters stayed at the Nassau Inn on their professors’ dime.

“I don’t want to say this lightly, but [the University] honestly did not care,” Kupupika said. “We didn’t really trust that if something happened to us, the University would respond properly. Especially because PSafe was used a couple of hours ago, when we had left, to corral us.”

Deputy University Spokesperson Michael Hotchkiss disputed this characterization.

“The University took seriously threats made against BJL members in 2015 and worked with law enforcement to investigate them,” he told the ‘Prince.’

Although a Public Safety investigation deemed the threat to be non-credible the next day, BJL members who spoke to the ‘Prince’ remember the fear, pressure, and scrutiny that followed.

The story was picked up by high-profile media outlets, including The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Yorker, spurring national conversations about institutional racism, historical monuments, safe spaces, and free speech.

On campus, the conversation often assumed an adversarial bent. A survey published on Nov. 21, 2015 found that student respondents held a largely negative view of the BJL sit-in. Among respondents, who made up 18 percent of the undergraduate population, the average rating of the BJL’s impact on campus climate was 3.91 out of 10, with a one being extremely negative and a 10 being extremely positive.

At the time, Joshua Tam ’18, who analyzed the survey data, told the ‘Prince’ that its results represented a “silent majority” on campus.

“The thing about the silent majority is—they’re silent,” said Tam. “If any one person tries to speak up against a mass of people, naturally they will be shut down and rejected if their mindset doesn’t match that of the group.”

But some members of what Tam deemed the “silent majority” made their voices heard. On November 23, 10 students formed the Princeton Open Campus Coalition (POCC) and penned an open letter to Eisgruber, expressing their opposition to the BJL.

The POCC circulated a petition titled “Protect Plurality, Historical Perspective, and Academic Speech at Princeton,” which garnered 1,818 signatures, nearly doubling the 1,045 signatures on the BJL’s petition listing the sit-in demands.

The POCC petition stated that removing Wilson’s name would constitute an “alarming call for historical revisionism and seeks to eliminate vindication of a significant historical figure who, despite his flaws, made great contributions to this University.”

The signatories described the proposed distribution requirement as “a thinly veiled attempt to impose the Black Justice League’s unilateral narrative upon all undergraduates through the conduit of the core curriculum,” and affinity housing as “a morally abhorrent and blatantly illegal call for what is essentially racially segregated housing.”

“[Free] speech is fundamental to Princeton’s role as an institution of higher learning and excessive political correctness stifles academic discourse,” the petition read.

POCC members were invited on Fox and Friends and profiled as “new student activists” in The New York Times. They wrote pieces in several prominent publications, including the National Review and Washington Post, advocating against the BJL’s “anti-intellectualism” and “historical revisionism.” In March 2016, POCC co-founder Josh Zuckerman ’16 testified before the House Ways and Means Oversight Subcommittee.

In his testimony, Zuckerman recalled multiple instances when the BJL had made “senseless ad-hominem attacks” towards students who dissented — an allegation that has recently reappeared.

According to Zuckerman, after a Black cofounder of the POCC expressed his disapproval of the BJL on Facebook, “[he] was then effectively labeled a race traitor. Someone asked him, ‘Why don’t you post something supporting your people, instead of trying to bring down those trying to uplift blacks?’”

Kupupika denied that she, or other members of the BJL, held such convictions. She pointed to the “huge meetings” that the BJL would hold for Black students, many of whom did not agree with their methods or demands, and took issue with the notion of questioning someone’s racial legitimacy or dedication to their racial group.

“That just doesn’t make sense,” she said. “What does it mean to tell someone they are not Black? Black is a social construction. I can’t remove someone’s Blackness from them."

Before the Subcommittee, Zuckerman went on to describe an instance that went “far beyond personal insults.”

“A student who wrote an article in defense of free speech in the campus conservative magazine woke up to find a shredded copy of the magazine taped to her door,” he said.

“[Protestors] seek to purge the university of ideas that make them feel unsafe,” he continued. “But no one at Princeton is unsafe. There has not been a single instance of violence, and no one has called for the subjugation of minorities... These attempts to bully students into silence —and, when that fails, to demand the creation of policies that will have similar effects — are utterly intolerable.”

As resistance grew, Kupupika, Crockett, and other BJL members continued to advocate on committees and task forces with administrators. Their efforts yielded affinity rooms in the Carl A. Fields Center, discrimination and harassment “training opportunities” for faculty, and the removal of the Wilson mural from the Wilson dining hall by the start of the next academic year.

Mural of Woodrow Wilson in Wilcox dining hall.

Courtesy of Mary Hui ’17 / University Press Club, 2016

It would take more than five years for the demand for a distribution requirement to take effect. In April 2020, the University announced a Culture and Difference requirement, beginning for members of the Class of 2024.

On the issue of removing Wilson’s name, the University’s Board of Trustees first commissioned a special committee to evaluate Wilson’s legacy by collecting community opinions.

The committee’s report, published in April 2016, called for the University to contextualize Wilson’s legacy, but came short of removing his name.

“Princeton must openly and candidly recognize that Wilson, like other historical figures, leaves behind a complex legacy with both positive and negative repercussions, and that the use of his name implies no endorsement of views and actions that conflict with the values and aspirations of our times,” the report read.

Despite their insistence that Wilson’s name remain on campus, the committee recommended other ways for the University to confront and atone for its racist legacy.

First, in October 2016, the University revised its informal motto, “In the Nation’s Service and the Service of All Nations,” which derived from a speech Wilson had once given. Drawing inspiration from Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor ’76, the new motto reads: “In the Nation’s Service and the Service of Humanity.”

In November 2017, the University provided additional funding to the Princeton and Slavery Project, an academic and creative endeavor founded four years prior meant to interrogate and document the University’s complicity in the institutions of American slavery.

The University then renamed West College to Morrison Hall, after Professor Emeritus and Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison. In April 2018, several spaces on campus were renamed after emancipated slaves who lived in Princeton, including Betsey Stockton and James “Jimmy” Johnson.

In December 2017, the Portraiture Nominations Committee commissioned portraits of Morrison, Sotomayor, Dean Carl A. Fields — the University’s first Black administrator — and Judge Denny Chin ’75, the first Asian American appointed as a federal district judge.

In September 2019, the University launched “Making Visible What Has Been Invisible,” a series of walking tours to highlight lesser-known stories from Princeton’s past, centered on the experiences of women and African Americans. The following month, a campus roadway was renamed after one of the University’s first African-American students, Robert J. Rivers Jr. ’53.

In the fall of 2019, the University unveiled “Double Sights,” a 39-foot-tall installation designed by acclaimed African American artist Walter Hood, to acknowledge Wilson’s moral complexity. According to the University, “The piece is intended to contribute to an ongoing conversation, not only about Wilson, but also about how we as a community grapple with history and how we move forward on issues of diversity, equity and inclusion.”

On Oct. 7, 2019, hundreds of students, faculty, and alumni gathered to protest the inauguration of “Double Sights.”

In public remarks, Eisgruber said the piece is “a stimulus to reflection and, as is the case today, an invitation to dialogue.”

“It is disruptive by design,” he added.

But for former BJL member Brandon Holt ’15, “The idea that we need a monument dedicated to a white supremacist in order for students to have a space to protest is incredibly flawed.”

After four years of deliberation, it seemed as though Wilson’s name would remain at Princeton indefinitely.

‘A different historical moment’: the BJL’s legacy on campus today

“Today, Princeton is still Princeton,” Professor Guild said.

“We have the same kind of students, same faculty, same president, but we’re in a different historical moment. We are now, depending on how you count, six years into Black Lives Matter, [three] years past Charlottesville, and three months past the murder of George Floyd.”

It was in this “different historical moment” that four non-Black seniors, Ananya Agustin Malhotra ’20, Andrew Gnazzo ’20, Gabriella Pollner ’20, and Janette Lu ’20, formed ChangeWWSNow, a group of SPIA undergraduates calling for anti-racist action.

On June 22, 2020, they wrote an open letter to Eisgruber reiterating the BJL’s demands for diversity training and the removal of Wilson’s name, as well as adding a few of their own, including divestment from the prison-industrial complex, a “critical intervention of ‘Double Sights,’” a core requirement in the policy school that “examines power, race, and identity,” and hiring more faculty of color.

The letter was signed by 75 percent of graduating seniors, 60 percent of rising seniors, and 64 percent of rising juniors in the policy school, and a similar set of demands from over 450 students and alumni of the policy school’s graduate program was published soon after.

On the same day that ChangeWWSNow released their demands, Eisgruber announced that he had asked senior University officials to put forth “specific actions that can be taken in their areas of responsibility to confront racism in our own community and in the world at large.”

According to University Spokesperson Mike Hotchkiss, “By tasking every member of the Cabinet, the President has signaled that every aspect of the University’s life – from teaching to research to operations to partnerships – can and must address these issues.”

On June 27, Eisgruber announced that the Woodrow Wilson School and Wilson College would be renamed the School of Public and International Affairs and First College, respectively. In an op-ed for The Washington Post, titled “I opposed taking Woodrow Wilson’s name off our school. Here’s why I changed my mind.,” he explained his change of heart.

“Princeton honored Wilson without regard to, and perhaps even in ignorance of, his racism,” he wrote. “And that, I now believe, is precisely the problem. Princeton is part of an America that has too often disregarded, ignored and turned a blind eye to racism, allowing the persistence of systems that discriminate against black people.”

“For me, the decision was wrenching but right,” he continued. “Wilson helped to create the university that I love. I do not pretend to know how to evaluate his life or his staggering combination of achievement and failure. I do know, however, that we cannot disregard or ignore racism when deciding whom we hold up to our students as heroes or role models.”

Referencing the murder of George Floyd, he added, “this searing moment in our national history should make clear to all of us our urgent responsibility to stand firmly against racism and for the integrity and value of black lives.”

BJL alumni criticized Eisgruber’s announcement as “woefully inadequate,” “long overdue,” and “cosmetic,” expressing their years’ worth of frustration with, in Kupupika’s words, the University’s “callousness toward student protestors.”

“Such symbolic gestures — absent a more substantive reckoning with lasting traditions perpetuating anti-blackness that our full list of demands addressed — reflect the University’s ongoing failure to confront deep-rooted issues that allow the racist status quo to remain intact under the guise of progress,” the alumni wrote.

“[The] University’s calculated and inadequate responses have remained the same: charge a committee, convene a task force, draft solutions, adopt very little, rinse and repeat.”

To close, the alumni urged the University to “heed the demands of current student organizers. We require more, current students require more, and the University must also require more of itself.”

On July 7, the SPIA announced a new diversity core requirement for graduate students and said it would be undergoing a “‘comprehensive review’ of its core curriculum” — in line with some of the graduate student petition’s demands.

Although the demands of ChangeWWSNow face dissent, as evidenced by around 20 students re-forming the POCC, organizers feel that they have been met with more approval than the BJL received in 2015.

Activist Ally McGowen ’21 remarked that administrators had received ChangeWWSNow’s demands relatively amiably, recalling that in a meeting, “[administrators] praised the wording of the letter, which I don’t think the BJL would have ever heard.”

Valeria Torres-Olivares ’22, another ChangeWWSNow activist, expressed a similar observation.

“It is important to note that we are not a majority Black group presenting these demands, and that might have played a role in how we were received,” she said.

From the start, ChangeWWSNow members have collaborated with other student activist organizations and Black student groups. Those groups, they said, heavily informed the drafting of their demands — many of which have not been enacted.

Current student activists see their work, in large part, as a “reiteration of the work of the BJL.”

Like the BJL, ChangeWWSNow demanded the removal of Wilson’s name “closer to the end of our list,” McGowen said.

“It’s going to take a long-term sustained effort to hold [the University] accountable on all of the other demands,” she added. “[The name change] was something that could be done in two seconds, even though they told the BJL it would take years.”

“Something we’ve been reflecting on, and we just spoke with BJL members last night, was how Princeton really responds to two things, and that’s shame and money,” said Torres-Olivares.

Today, BJL alumni share their experiences, ideas, and advice with current student activists, resolved not to let their demands be indefinitely deferred or forgotten.

The original ChangeWWSNow activists, as graduating seniors, have also passed down the torch. “We reached out and came to work with Ally and Valeria, who are class of ’21 and ’22, to transition into having current students as lead organizers,” said Lu.

“A lot of the demands we made in 2015 were not new,” Anyanwu said. “They were made as early as the ’90s. They were made as early as the ’60s.”

In the words of Ella Jo Baker — the civil rights era icon whose footsteps the BJL sought to follow — “the struggle is eternal.”

“The tribe increases,” Baker continued. “Somebody else carries on.”

Five years after the Nassau Hall sit-in, students see themselves as doing just that.

Correction: A previous version of this piece incorrectly claimed that the Princeton and Slavery project was founded in 2017. The project was founded in 2013 but received major additional funding in 2017. The ‘Prince’ regrets the error.