During the Great Recession of 2008, college students saw the global economy in shambles and left the humanities in droves, out of fear such areas of study would lead to unstable, low-paying jobs. Yet, when the economy recovered, they never returned.

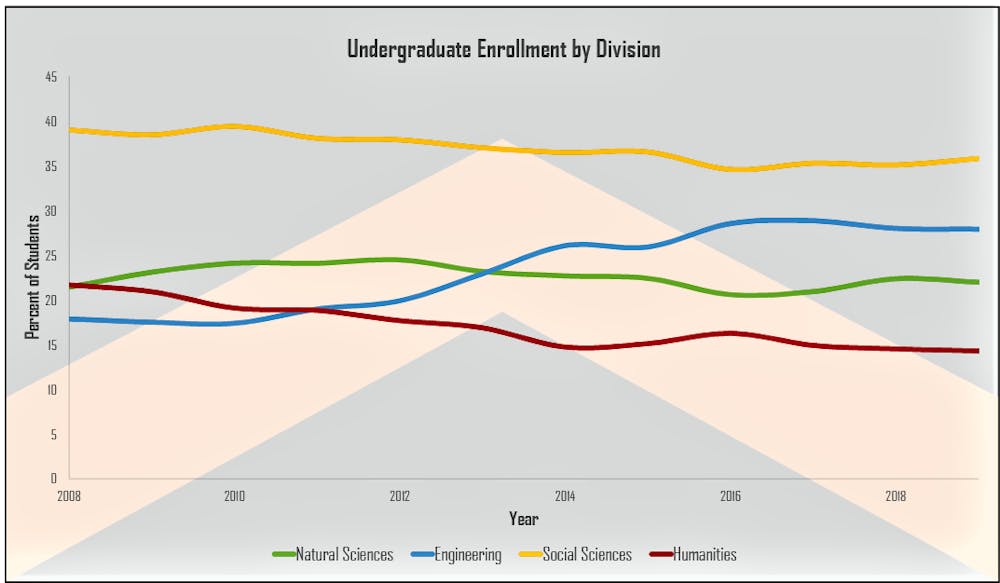

Enrollment data from the Office of the Registrar that I recently compiled illustrate the damage that the Great Recession inflicted upon the humanities at Princeton. Now, with the world in its worst economic slump since the Great Depression, the coronavirus pandemic has the potential to deal the final blow to departments that are still reeling from the last downturn.

Half of all undergraduates currently declare concentrations in six of 37 available subjects — history, politics, economics, computer science (COS), operations research and financial engineering (ORFE), and the Woodrow Wilson school.

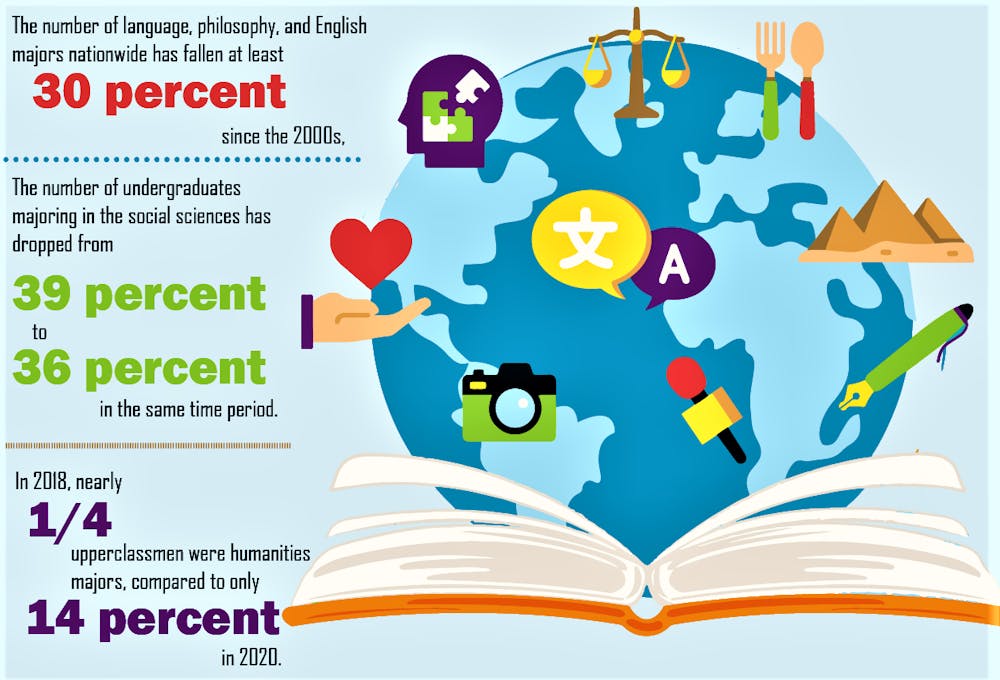

“The wake of the financial crisis had a big effect on the humanities,” Religion Department Chair Judith Weisenfeld told me. Nearly a quarter of upperclass-students were humanities majors in 2008. Just 14 percent are today.

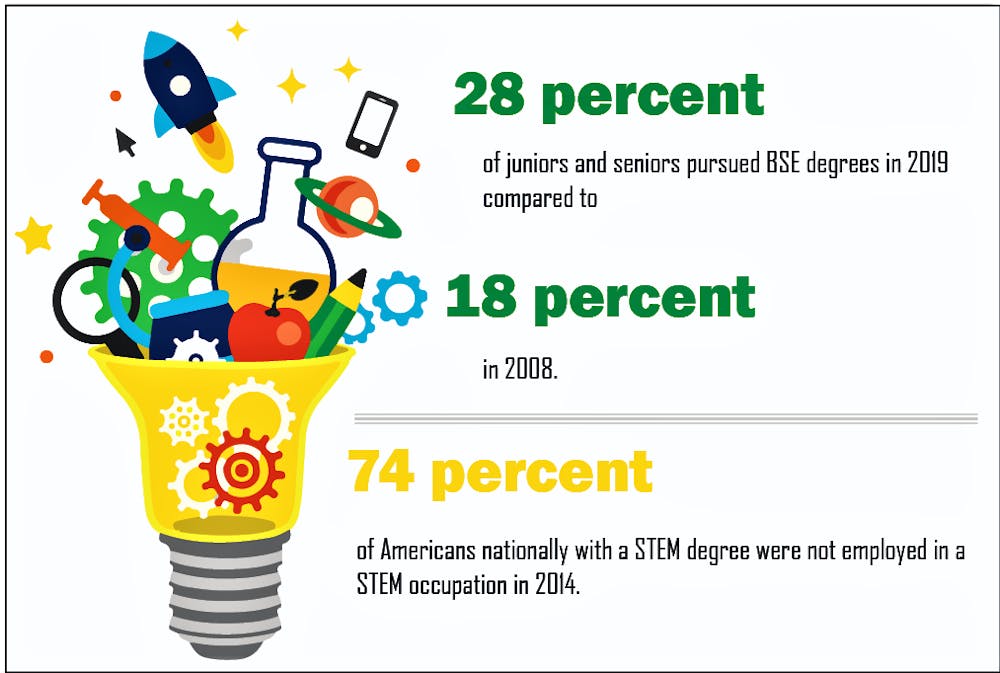

Social sciences also dropped in popularity to a lesser extent, from 39 percent to 36 percent, over the same period. The natural sciences — while initially seeing a brief rise — had no long-term change. On the other hand, engineering surged. Twenty-eight percent of juniors and seniors pursued BSE degrees last year compared with 18 percent in 2008.

Harsimran Makkad / The Daily Princetonian

Princeton’s experience is hardly unique. It’s part of a larger national trend. The number of language, philosophy, and English majors tumbled at least 30 percent since their peaks in the 2000s, according to The Atlantic.

“We feel the impact of the broader cultural devaluing of the humanities, and that comes from this relentless linking of employment to major,” Weisenfeld said.

COS has almost exclusively fueled engineering’s expansion at Princeton. Whereas only one in thirty-three undergraduates were COS majors in 2008, one in eight were in 2019.

Harsimran Makkad / The Daily Princetonian

“There’s a combination of enthusiasm, jobs, and opportunities for innovation that get people excited about computer science,” Computer Science Department Chair Jennifer Rexford told me. She said that interest in COS skyrocketed in the late 1990s and then crashed when the dot-com bubble burst in 2001. This time around, advancements in technology seem to be spurring long-lasting job creation.

She also credits COS’s success to the department’s efforts to make introductory classes more accessible. Almost 60 percent of Princeton students take COS 126, Computer Science: An Interdisciplinary Approach.

“We’ve done a lot to try to make the educational experience boutique, even though it’s at scale,” she said.

Harsimran Makkad / The Daily Princetonian

The Registrar’s data reveals trends within Princeton’s academic divisions that resulted from world events and new departments. ORFE had a brief dip following the Great Recession but soon recovered to its pre-crisis enrollment by 2013. After the neuroscience department started offering a concentration in 2015, students abandoned chemistry and psychology to join it. Likewise, the Woodrow Wilson school attracted would-be politics, economics, and sociology majors when it scrapped its restrictive application process in 2013.

Art & Archaeology has halved in size since its peak in 2010. The number of English students shrank 32 percent during the past decade. Comparative Literature is merely a third as big as it once was. Religion went from being the fourth most popular of 14 humanities concentrations to being tied with German as the second least popular.

Weisenfeld explained that the humanities, especially her department, face two main challenges in attracting students. Aside from private and a handful of well-funded public high schools, not many secondary schools teach religion or related fields as academic disciplines. In turn, few students come to college looking to study them. For those who do, the humanities departments compete against each other to split the same small pool of undergraduates among themselves.

Harsimran Makkad / The Daily Princetonian

Weisenfeld also suspects that Princeton’s prohibition on double majors forces students on tight budgets to pick the sciences for pragmatic career reasons over their love of arts and culture. The upside, she said, is that the humanities’ course enrollment isn’t falling, so they make a significant contribution to liberal arts education.

Rexford called the concentration of students in COS “unhealthy.” She urged underclass-students — or their parents — who are concerned about their financial futures to consider earning the “applications of computing” certificate while majoring in the humanities.

“It’s a waste of resources to have immensely qualified faculty doing really interesting work and teaching and not having the student interest [in them],” she said.

The shame of the humanities’ decline is that people who study them — contrary to conventional wisdom — don’t have dismal employment prospects.

A 2018 report by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences determined that humanities majors eventually catch up in earnings to their peers who studied science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), and have comparable levels of job satisfaction. Harvard economist David Deming argues that their fields teach them “soft skills” — like adaptability and critical thinking — that pay off when they enter law, management, or business. The Census Bureau found in 2014 that 74 percent of Americans who hold a STEM degree aren’t employed in STEM occupations anyway.

Princeton’s liberal arts model lets students combine their passions. It may be better to join a small department and study a second interest in a larger department as a certificate. The Gallup-Purdue Index Report of 30,000 college graduates found that they were more likely to be engaged at work if they connected well with a professor. Such relationships are definitely easier to build in departments where advisers don’t have to divide their attention between a dozen students.

Nor does a major guarantee a certain lucrative job. The ORFE and economics majors of the Classes of 2008-2010 undoubtedly struggled to get finance jobs while Wall Street saw mass layoffs. The dot-com bubble showed that the tech field isn’t invulnerable either. My own major — Geosciences — is one of the most “marketable” because of its relevance to oil exploration (not that I picked it for this reason). But an ill-timed price war between Russia and Saudi Arabia, coupled with the coronavirus slowdown, have devastated American petroleum firms.

Whichever fields seem “hot” today may not be as employable by graduation. One advantage of the humanities is that they’re not tied to the unpredictable fortunes of a particular industry.

Under lockdown, first years and pre-frosh have a rare opportunity to ponder their futures at Princeton with less of the usual pressures of school. I encourage them to think about how they can best leverage Princeton’s resources to pursue whatever excites them. If this pandemic has taught us college students anything, it’s that the world can wreck our carefully planned careers at a moment’s notice.

The humanities declined after the last recession. But coronavirus may be the chance to set up their resurgence.

Liam O’Connor is a senior geosciences major from Wyoming, Del. He can be reached at lpo@princeton.edu.