Thomas Roche Jr., the Murray Professor of English, Emeritus, died peacefully at 89 years old after a long illness in Beachwood, Ohio on May 3. He is survived by his husband, Robert H. “Bo” Smith.

Roche — known better as T.P.R. or simply T.P. to his students — was a leading scholar in epic and Renaissance poetry. His work significantly shaped the development of Spenser studies (scholarship related to Edmund Spenser, author of the 16th-century epic poem “The Faerie Queene”) in the second half of the 20th century.

“TPR was the consummate host, the consummate professor, the consummate Spencerian, the consummate mentor, an extraordinary friend. And one of the most caring, wicked, hilarious, big hearted people I know,” reflected John Smelcer ’98, a concentrator in the Woodrow Wilson School and a founding member of Princeton Shakespeare Company (PSC), in an email to The Daily Princetonian.

“Literally generations of students, professors and fellow actors will miss him dearly,” he added.

A leading scholar

Roche was born on April 19, 1931 to Thomas Patrick Roche, Sr. and Katherine Walsh Roche. The New Haven native graduated as valedictorian from Hamden Hall Country Day School and earned his bachelor’s degree from Yale University in 1953. He earned his master’s and PhD from Princeton before joining the University as a research associate and lecturer in 1960. He was appointed as faculty the following year and soon became a fixture of the English Department.

After transferring to emeritus status in 2003 at Princeton, Roche went on to teach with his husband at Arizona State University, the University of Notre Dame, and John Carroll University, where he and Smith became the first duo to win the Outstanding Part-Time Faculty Award in spring 2019. Roche remained in the classroom until six weeks before his death.

In 1991, Roche was awarded the University’s Behrman Award for Distinguished Achievement in the Humanities. He also held an honorary master’s degree from Oxford University and was chosen by the family of F. Scott Fitzgerald as the literary trustee of the author’s estate.

Along with numerous articles in academic journals, Roche’s published works include “The Kindly Flame: A Study of the Third and Fourth Books of Spenser’s Faerie Queene” (Princeton University Press, 1964), the “Editorial Apparatus” to it (1984), “Petrarch and the English Sonnet Sequences” (AMS Press, 1989), and “Petrarch in English” (Penguin Classics, 2005). Roche also edited, with the assistance of C. Patrick O’Donnell, the Penguin Classics version of “The Faerie Queene” (1979). At the time of his death, he was working on a book about the role of the Muses in art history.

Roche was also the founder and co-editor for many years of “Spenser Studies: A Renaissance Poetry Annual” and the founder of the Spenser Society, an international organization of which Roche served as president and other leadership positions.

A professor with personality

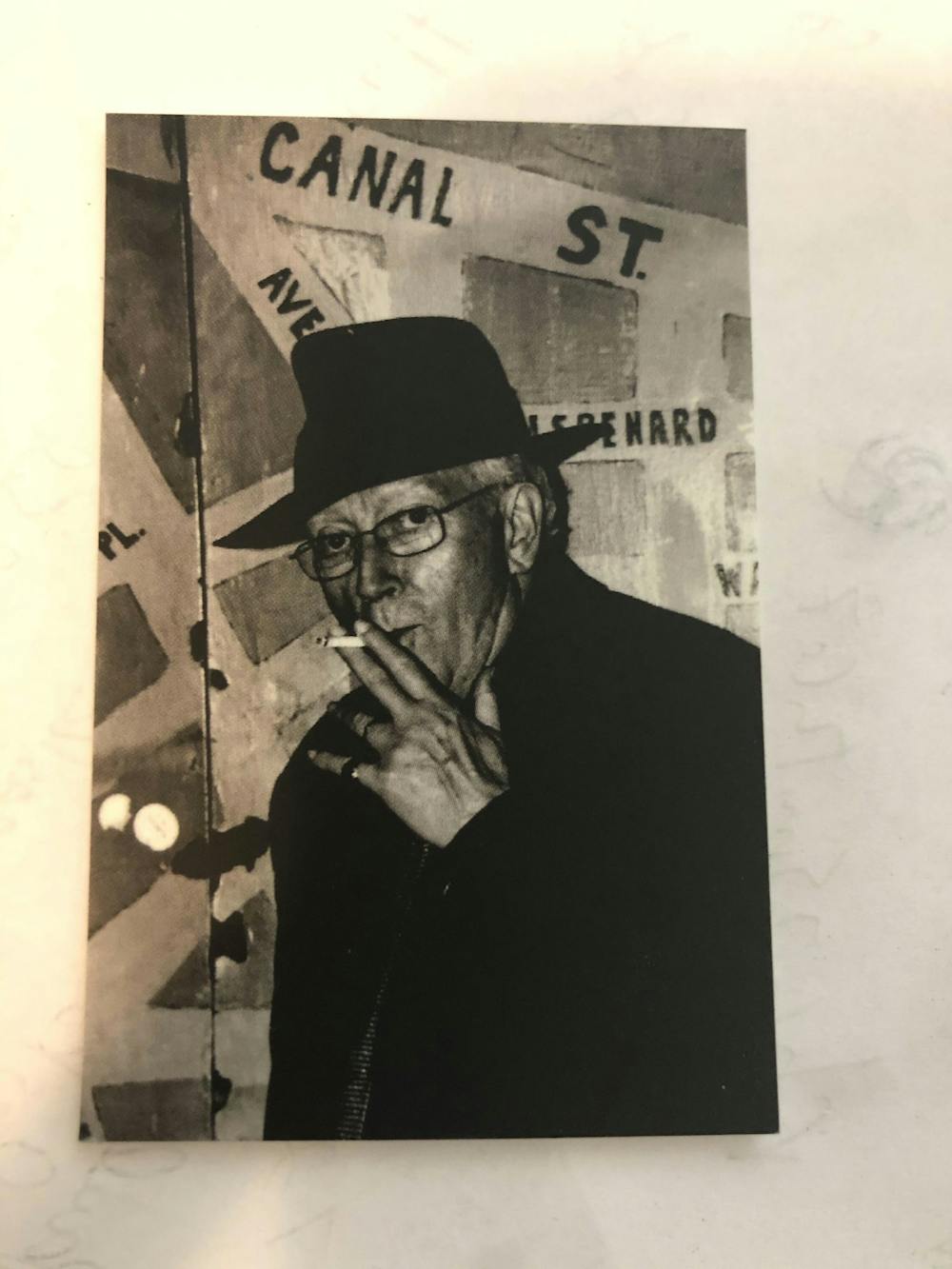

His students and colleagues remember Roche as a man with character. Davis McCallum ’97, an English concentrator and founder of PSC, remembers Roche sporting borsalino hats and smoking Benson & Hedges 100’s cigarettes.

“He got up every morning and put his passport in the pocket of his jacket, and he did this, he said, ‘just in case,’ as if someone was going to spontaneously invite him to go to Paris for lunch or something,” McCallum said.

“He was a bit of an anachronism,” recalled James Stanford ’98, who performed with Roche and had him as a junior paper and senior thesis advisor in the English Department. “He was out of central casting from a professor from 30, 40 years prior in a wonderful way.”

McCallum met Roche as a first-year when Roche taught ENG 201, a then-prerequisite for aspiring English concentrators.

“At one point, he handed back our first papers that we’d written from the semester, put the papers down on the desk, sat on the seminar table and said, ‘I’ve been teaching at Princeton for 35 years. This is the single most grievous batch of papers I’ve ever had in my teaching career. I will give them back at the end of class,’” McCallum said, laughing.

“We just kind of looked at each other like, ‘He said grievous?’ It was stunned silence,” McCallum added.

“He relished the unexpected gesture, and he was very funny, and he had a sly, generous, but sometimes wicked sense of humor,” McCallum continued. “He had a kind of impish look in his eye most of the time.”

Like McCallum, Smelcer and other students of Roche describe class with the giant of the English Department as equal parts illuminating and entertaining. Smelcer shared a list of one-line zingers from Roche’s lectures. Anne Margaret Daniel GS ’99, a graduate student of Roche — whom she called “a Renaissance man in every sense of the word” — recalled his ability to make the works he taught relevant and exciting.

“Tom always made any century that was interesting and engaging feel much closer to you,” Daniel said. “He always had a connection; he always found a connection between the medieval, the Italian, the Irish, the English literature — it didn’t matter. There were connections that he found and engendered and then he shared with his students.”

Roche’s colleagues remember his relationship with literature as almost magical.

English professor Jeff Nunokawa recalled how Roche “held court in the windowless Hinds Library down in the Basement of McCosh Hall, where in the words of the poet he spent his life studying, he ‘made a sunshine of the shady place’ ... with his stories about the ghosts of Princeton past, and the ghosts in English Literature.”

English lecturer Sarah Anderson enlisted Roche’s talents when she was teaching “The Faerie Queene” in a junior seminar on the character of Merlin, turning to Roche to read from Book III of the poem in her class.

“On the day and at the hour, Tom entered the classroom and claimed the students’ attention: he bowed slightly, and he did not so much shrug his cloak from his shoulders, as twirled it slightly, so it reposed perfectly upon a chair,” Anderson wrote. “As he read, Spenser’s Merlin gleamed before us. The ligature between all that Tom knew — of Spenser, epic, Neoplatonism, a medieval and a newer world — was simply in Tom’s voice.”

A flair for the dramatic

Roche became involved with the fledgling PSC during its second year of existence when he played Duncan and the Porter in PSC’s 1995 production of “Macbeth” directed by philosophy concentrator Leo Kittay ’96. The October production took place in the round in East Pyne Courtyard and featured a late-night Halloween showing.

“He just had this childlike joy in being a part of this. It’s about his joy and willingness to play with us and to try things out, and he would volunteer ideas and we would break down the text together,” Kittay said of Roche’s involvement in “Macbeth.”

“He made the production so much more everything than it would have been without him,” Kittay continued. “It was more interesting, it was more intellectually stimulating because we had his expertise.”

“And it was comforting to have him there because he had this incredibly sophisticated and trained eye on this stuff,” Kittay added, “so it was comforting for me as a director to be able to look to him and say, ‘I think this is working, right?’”

After “Macbeth,” Roche remained involved in the theater scene at the University, participating in productions like “Julius Caesar” with PSC, “The Merchant of Venice” with Princeton Summer Theater, and “Into the Woods” with Princeton University Players.

“There was something very poignant and instructive about his willingness to jump into these productions with us,” wrote Damian Long ’98 in an email to the ‘Prince.’ Long met Roche shortly after seeing him in “Macbeth” and went on to direct Roche in “The Merchant of Venice” — and Roche went on to advise Long’s senior thesis.

“He was, at the time, one of the world's leading experts on Edmund Spenser, and a revered elder statesman in an impressive English Department,” Long continued. “And yet, here he was: an amateur actor — as we all were — doing something that he was not well-known for, that he sometimes felt a little uncomfortable doing.”

“He lived what he taught, and if he could foster a love of Shakespeare in Princeton students by supporting our shoestring productions with his presence, that's what he would do,” Long added.

The final course Roche taught at the University, “Shakespeare: From Page to Stage,” harnessed both Shakespeare scholarship and performance. Roche brought on Smith to help teach and serve as a director and acting coach for students in the course. It was this “Tom and Bo” course that would lead Roche and Smith to teaching positions at several colleges beyond Roche’s retirement from the University.

In addition to his involvement in theater outside of the classroom, Roche served as the University’s mace-bearer in academic processions beginning in 1993, a position which Anderson finds exemplary of Roche’s persona.

“[I]t takes a person with both an extraordinary sense of dignity and an equally extraordinary sense of the absurd to be a University mace-bearer,” Anderson wrote.

Photo courtesy of Robert "Bo" Smith

A generous legacy

Roche left a lasting impact on his field. Roche’s book “The Kindly Flame” is described by Roland Greene GS ’85, a former student of Roche’s, as a corpus of criticism “with a durability comparable to the work of” the scholars of “the heroic age.”

Greene wrote, “What keeps us reading ‘The Kindly Flame’ fifty years after its publication is that the book obliges us to think on our own — whether we call it our ‘experience’ or something else — about how to make meaning in Spenser's poem.”

“Professor Roche trained some of the best scholars of the early modern period at Princeton,” Simon Gikandi, the Robert Schirmer Professor of English and chair of the English Department, wrote in an email to the ‘Prince.’ “In addition to Greene, some of Professor Roche’s students who have gone on to define the field include Margreta de Grazia, a great Shakespearean at Penn, and Peter McCullough (Professor of English) at Oxford and Gavin Jones (Professor of English at Stanford), all part of a Princeton generation that transformed the study of the early modern period.”

Roche’s legacy, however, is seen best not in academic achievements but in the deep relationships he forged with the people in his life.

“He was a co-conspirator, a mentor, a friend to many of us — and could toggle among those roles effortlessly,” Long wrote.

Gikandi has been “astounded by the collective sense of loss felt by members of the English Department and their genuinely fond memories of him” expressed in the influx of remembrances about Roche. Roche’s husband, Smith, has also been overwhelmed by the “absolute tsunami of letters, emails, texts, flowers, donations that have poured in from the moment word got out.”

“I’m not exaggerating when I say there have been some days that I’ve stayed at my laptop for eight hours trying to catch up with all the responses. They’ve been immensely touching, and a lot of them are from people I don’t know, people he taught 50 years ago,” Smith said. “I got some from a publisher in Finland and an academic in Tokyo. His reach was amazing.”

As those who knew Roche describe their beloved professor, mentor, and friend, one word echoes across their reflections: generous.

Nunokawa described this admirable spirit of Roche as “unstinting hospitality and generosity” and a “power to find in almost anybody something redeeming.”

Former students described the many expressions of Roche’s generosity such as opening his home to them for dinners, taking care of them when they were sick, encouraging them to apply for awards and fellowships, and helping them in their next steps after graduation.

Smith recalled Roche’s response when a faculty member asked why he would want to take students out to lunch and dinner: “Because they’re infinitely more interesting than the faculty.”

“I have never, ever, known a more generous teacher, and I never will,” Daniel said. “He was generous with his time. He never said no to any request for academic help to my knowledge. He bent over backward to help undergraduates get everything from summer internships to jobs out in the real world.”

Daniel has a physical reminder of Roche’s generosity in the old Underwood typewriter he gave her. The typewriter was given to Roche from A. Walton Litz ’51, the late professor of English and former English Department Chair, and originally belonged to the poet W.H. Auden.

McCallum has another way of remembering Roche’s impact on his life: the late professor is the namesake of McCallum’s oldest son.

“He’s one of the most important people in my life,” McCallum said. “He really epitomizes what I think you hope for as a student and now as a parent in a teacher as someone you’re going to encounter at a certain point in your life and they’re going to open up a door to a whole different possibility and invite you to walk through it.”

Beyond his husband, Roche is survived by his youngest sister, Katherine Roche Bozelko, her husband, Ronald F. Bozelko, and three nieces: Chandra Bozelko ’94 of Orange, Conn., Alana (Paul) Choquette of Chevy Chase, Md., and Jana (Christopher) Simmons of Plymouth, Minn. He was predeceased by his younger sister, Nancy K. Roche of Bethesda, Md.