Following pledges from several Ivy League schools to divest from fossil fuels, students, alumni, academics, and activists met over Zoom on Friday to discuss where the University stands. The event was a part of virtual Reunions programming.

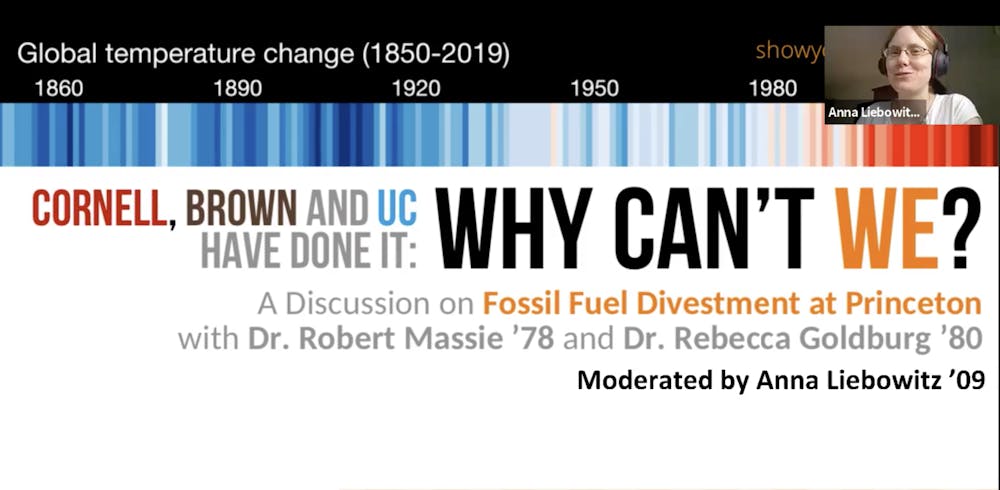

In a panel entitled, “Cornell, Brown, and UC Have Done It: Why Can’t We?: A Discussion of Fossil Fuel Divestment at Princeton,” Dr. Rebecca Goldburg ’80 and Dr. Robert Massie ’78 explored the merits and challenges of advocating for a financial response from the University to the threat of climate change.

The panel was hosted by members of Divest Princeton, a group of students, faculty, and alumni calling for the University to divest its endowment from fossil fuel companies. They submitted a proposal outlining their recommendations to the Resources Committee of the Council of the Princeton Community (CPUC) in February, and await a response. In the meantime, this event was held to spread awareness among alumni about their cause.

Anna Liebowitz ’09, a founder of Divest Princeton, moderated the panel. She began the event by describing the content of the group’s open letter to President Eisgruber ’83, which, in addition to the CPUC proposal, advocated removing both direct and indirect investments in fossil fuels, preventing new research from being funded by the industry, and establishing a body to oversee ethical reinvestment.

The Zoom event hosted by Divest Princeton

Photo Credit: Zachary Shevin / The Daily Princetonian

Goldburg is the Director of Environmental Science and Research at The Pew Charitable Trusts, though she spoke at the event in her personal capacity. She has worked with large companies to reduce antibiotic use on farm animals, studied and optimized sustainable aquaculture, and helped install federal regulations for agricultural biotechnology.

Massie is an activist and author on issues of global leadership and corporate accountability, social justice, and climate change. He has led organizations including Ceres, the Global Reporting Initiative, the Investor Network on Climate Risk, and the New Economy Coalition.

Goldburg was one of three women to bicker and integrate eating clubs in 1978, and also took part in the movements for divestment from apartheid in South Africa during her time on campus. Massie was heavily involved in both of these causes as an undergraduate as well; he went on to dedicate much of his early career to the relationship between the United States and South Africa in the apartheid era.

Both spoke of their experiences as student activists and the message they believe University actions can send.

“I think sometimes, while Princeton thinks of itself as a progressive place, it has to be pushed in order to do the right thing,” said Goldburg. “Students need to recognize this: their effects over time, cumulatively, can cause the University to question itself and eventually lead to change. It’s not a sudden process.”

As the title of the event suggested, several of the University’s peers have recently taken action to divest from the fossil fuel industry. The panelists discussed their belief that academic, science-driven institutions like Princeton have a unique responsibility in divestment debates — that their impact was considerable in the 1980s and can be again.

“University actions made clear that apartheid was ethically unacceptable to major institutions, and helped catalyze and support a lot of other action that led to its downfall,” Goldburg said. “Our situation with fossil fuel today has many similarities.”

Goldburg added that divestment’s impact is both internal and external. Not only does it communicate to the larger public what side they should be on, she argued, but it also brings the issue closer to home for members of the University community.

“If Princeton declares that it will divest, I think it will be the clear signal to [faculty, alumni, and students] that dealing with climate change is a major institutional priority,” she said. “That will prompt people to take a hard look at the related issues and ask themselves, ‘What can I do? How can I contribute?’”

Massie noted that the benefits of divesting are twofold: the University has a moral responsibility to combat the impending threats of climate change, he explained, as well as a fiduciary duty to remove itself from the declining coal and fossil fuel industries.

“[Divestment] is a critical thing. It engages the core of the University, the safety of everybody in it, the safety of the planet — and it justifies a strong reaction. Not to mention that with a dying industry, you do not want to continue investing,” he said.

An audience member asked the panelists about the ongoing relationship between the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment and ExxonMobil, one of the world’s largest oil and gas companies. The connection has been scrutinized by Divest Princeton as creating a conflict of interest in climate research.

Both speakers admitted the question of funding to be nuanced. “The question of who it’s acceptable to take money from is quite complicated,” Goldburg said.

“These oil companies use these programs to prove that they really ‘care.’ So they give somebody a million dollars, or a hundred million dollars, and then they make that back in a single day. It’s a smokescreen,” explained Massie.

Ryan Warsing, a graduate student at the Woodrow Wilson School and an organizer of Divest Princeton, concluded the meeting on a “note of activism.” 830 students and alumni have already signed a Divest Princeton letter pledging not to donate to the University “until it divests from fossil fuels.” Warsing told the alumni that their tool for action is donation, and to support Divest Princeton, they could reroute their usual donations to the University to organizations promoting social change, such as the Climate Justice Alliance.

Warsing added that action is “particularly impactful” now because the CPUC Resources Committee is currently deliberating the group’s proposal. He encouraged participants to email the Committee in support of climate action and to copy President Eisgruber on the message.

“The iron is very hot right now for this kind of action,” Warsing said.