It’s 8 p.m. on a Wednesday, and Paul Frymer, professor of politics and director of the Program in Law and Public Affairs, is sprinting around his house, trying to wrangle his kids to bed. He — finally! — gets teeth brushed, pajamas on, bedtime stories read, and lights turned off. Then he collapses into an armchair, opens his laptop, and begins recording Thursday’s lecture for POL 220: American Politics.

In the wake of the University’s March 11 move-out order, athletes lost their spring seasons, seniors in STEM fields abandoned their theses, and couples reckoned with unexpected long-distance relationships. Students mourned the transition to a fully-virtual spring semester. But they’re not alone in facing difficulties. On the other side of the computer screen, Princeton’s professors are also grappling with unprecedented challenges, as they navigate what Frymer deemed “not an ideal semester.”

Completely booked schedules — typically filled with morning meetings, lectures, meals with colleagues, office hours, and guest appearances — have been replaced by days in which professors are confined in and work from their homes. This new normal, however, isn’t to say that professors’ responsibilities have suddenly disappeared. Most are working as hard as ever. Furthermore, a subset is confronting a unique challenge: balancing teaching, research continuity, and their children.

Widespread closure of schools and day-cares across New Jersey means that kids of all ages — from preschoolers to high school seniors — are back at home full-time. Many Princeton professors now find themselves juggling their roles as educators with their new ones as full-time parents, forced to fill both at all hours of the day and night.

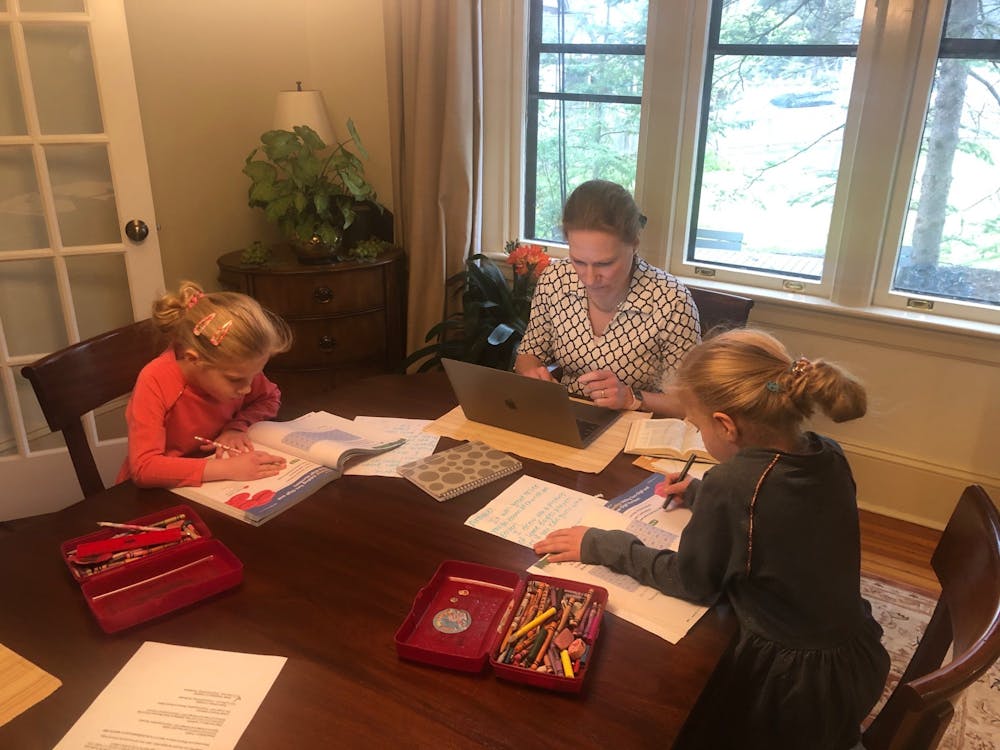

Professors with young children have often been forced to set aside their jobs for the majority of the day and spend long hours looking after their children. AnneMarie Luijendijik, professor of religion, head of Wilson College, and mother to twin seven-year-old daughters, Rosemarie and Annabel, who were profiled by The Daily Princetonian a few months ago, describes how being with her kids at home has impacted her work.

“My research has been on the back burner a little, unfortunately,” she said. “I feel bad about it. It eats me up from the inside.”

Other professors have had to split their days in two: parenthood when their children are awake, teaching after they’re put to bed.

“I want to do the best I can do,” said Frymer. “But I don’t have as much time. But I am not free until 9 o’clock at night and I’m pretty tired.”

And even when it comes time to teach, professors have had to adjust their methods, their expectations, and their communication with students.

Some, like Efthymia Rentzou, professor in the humanities and associate professor of French and Italian, have switched to asking students to respond to Blackboard discussion posts and answer sets of questions prior to class. Teaching, she says, has become “a little more planned than before.”

Many professors, such as Elisa Dossena, a lecturer in French and Italian, are working overtime to make more contact with their students and conference with them to go over assignments and examinations. Others are rethinking their courses entirely.

Before the switch to remote instruction, Russ Leo, associate professor of English, had changed his course, ENG 325: Milton, to a seminar-style in order to create a more participatory environment. Forced to teach over Zoom, he has reverted back to the lecture-style, explaining that it is difficult to maintain an engaged, discussion-based seminar online and that different time zones make it difficult to find convenient class times for all his students to meet.

Leo, however, has found a new source of inspiration for his course: time at home with his six-year-old.

“To spend the majority of my day with a six-year-old whose mind is just making so many connections, working at such speed,” he said, “and then going to teach a text [“Paradise Lost”] that is so much about learning, error, and innocence is really remarkable.”

Shelter-in-place orders haven’t just affected professors’ academic work. They’ve had to reckon, too, with the upending of their family routines and rules. Luijendijik said she and her husband have asked their children “to chip in in a different way than they normally do and they help without complaining.” Dossena said that her eleven-year-old son, who had had previously been restricted in his internet use, now has free, regular access on account of online learning.

“I had to give them free access to the internet for their classes,“ she said, “and they are now in front of a screen for much longer than before. I lost control in the sense that I have no way to check to know what they’re really doing and if they’re in class or doing homework or not.”

Other professors have adopted drastic measures to manage their newly crowded and chaotic households. According to Frymer, some of his colleagues have resorted to “using their cars as their office to get some privacy” in order to get some work done.

And though there’s no shortage of family-bonding time in a quarantined household, professor after professor mentioned acutely missing the classroom’s social vibrancy.

“You know what is missing for everybody?” asked Dossena. “The social part. The people. I am missing the students. I miss looking at their real face, and not their face through the screen. I miss talking before and after class and joking around.”

While professors are dealing with the same shorter attention spans and loss of community as students, they emphasized wanting their students to reach out to them when needed, offering to help them any way they can.

“We realize that this is hard,” said Luijendijik. “I wish them all the best in finding a new rhythm. Be a little bit patient with yourself as you figure it out.”

These Princeton professors have always been both parents and teachers. But now, as they grapple with the fallout of COVID-19 in New Jersey, the state with the second-highest per capita infection rate, those two worlds are at odds, each demanding their undivided attention.

And for the most part, professors seem to be taking the same attitude as their students.

“Well,“ said Frymer, “you figure it out as you go along.”