Jordan Thomas ’18 was just beginning a statistics course during his first spring semester at the University when he made a startling realization. Many of the other students in his class had already taken college-level statistics in high school.

“I was in a classroom with students who very clearly had taken AP Statistics,” he said. Thomas came to Princeton from an urban high school in Newark, N.J., that didn’t offer many opportunities to pursue advanced math. He knew that everyone else had a clear advantage over him, but he still pushed himself to do well.

“I was playing catch-up hard,” he said. The next few weeks weren’t easy for him. He described having to stay up late to understand basic concepts that his classmates already knew. By the end of the semester, he had closed the gap and outperformed some of his better-prepared peers, putting him on the road to a Rhodes scholarship. During an interview in Oxford’s Cornmarket Street Starbucks, he remembered just how much more of an edge some of his classmates at Princeton had.

“If you come from a family that has legacy status at an Ivy League [university] and maybe, if you’re really lucky, has legacy Rhodes,” he said, “you’re coming in with a different mindset about what you need to do to get that goal.”

Thomas’s astute observation is a rarely acknowledged fact of the Ivy League: its students still suffer from the American education system’s inequalities. Graduates from the best and worst high schools in the country go to the same lectures, take the same exams, and occasionally compete for the same small pool of top grades. First-generation and low-income (FLI) students largely enter at a profound disadvantage.

Instructors often compare student performances without knowledge of their prior preparation. Though the difference in high school background is most pronounced during the first weeks of a student’s first year, the effects of the disparity are long-lasting. This raises the question of who succeeds at places like Princeton and why.

Fierce competition to give students a leg up in college admissions is fueling an educational arms race at private and public high schools in affluent areas. A 2013 Temple University study confirmed that this was the primary reason behind the expansion of Advanced Placement (AP) curricula in California’s upper-middle-class school districts.

The Washington Post reported several years ago that 90 percent of first-year students at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology in Northern Virginia had already taken Algebra II or a higher math class. For reference, Algebra II was the highest level of math for half of seniors nationwide, and Calculus I was for another fifth, according to an American Enterprise Institute study from about the same time.

“Students, not just at TJ but all over the region, are accelerating in math at a very rapid rate,” then-principal Evan Glazer said.

Flip through the pages of elite high schools’ catalogs, and it’s easy to find exotic course titles that the average Joe wouldn’t see until their later years of higher education. Multivariable calculus and linear algebra — subjects normally reserved for college sophomores or juniors — are widespread among moneyed high schools. Thomas Jefferson students can take electrodynamics and differential equations. Phillips Academy Andover offers organic chemistry. Stuyvesant High School teaches artificial intelligence.

This acceleration is mainly happening in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). Advanced humanities classes are rare beyond a handful of private schools, based on my qualitative impression of looking through their websites. The connection between taking rigorous high school classes and performing better in college has been documented in multiple academic studies.

“A lot of STEM majors come into the University with very substantial backgrounds in science and mathematics from good high schools,” former University President Harold Shapiro GS ’64 said.

College admissions disproportionately funnel elite high schools’ graduates into a handful of institutions through feeder networks. One in 20 undergraduates at the University, for example, came from just five high schools. Four of them were world-class magnet schools, and the other was the $69,000 per year Lawrenceville School.

American Secretary to the Rhodes Trust Elliot Gerson recognized that students have rocky first years because they attended high schools that provided poor college preparation. For that reason, he said there’s a process that allows universities to petition him to waive the scholarship’s minimum grade point average (GPA) requirement. But Rhodes district committee member Nicholas Allard ’74 stated that he had seen “very few” of these waivers used.

University of Georgia professor Gregory Wolniak has tracked how prior academic preparation affects students’ college performance. A 2010 study that he co-authored found that graduating from high schools with “ample resources” had a positive effect on first-year grades, while exposure to violence did the opposite.

“Attending a high school that is a known pathway to institutions like Princeton has a direct resource benefit for [a] student. In some ways, it can serve to offset other deficiencies a student might have if they’re not the strongest,” he told me.

But the puzzling aspect of this educational divide is that it’s not exclusively reserved for students from the richest families. Harvard sociologist Anthony Abraham Jack chronicled in his book “The Privileged Poor” that poor kids who attended elite private high schools felt more comfortable and performed better at a top tier college than their public school classmates of similar socioeconomic backgrounds.

“We have a horrendous math and science foundation in our public school system. If you want to get into that, you have to get into a private school,” said Rhodes finalist Sam Rob ’18, a Woodrow Wilson School concentrator . He was sure that success in STEM at Princeton “goes back to your high school foundation.”

No current students would speak further on the record about this subject, but it has appeared in the University’s popular discussion boards lately. It seems they agree that students from strong high schools have the greatest advantage in STEM subjects.

An anonymous user on Tiger Confessions++ wrote, “the [science] courses are designed so that only those with prep school education and who are trained to have a scientific mindset can make the grades[.] There are slim to none low-income students from bad high schools, like me, who have managed to beat the curve.” Several classmates responded that they agreed.

Contributor “belcalis” posted on real talk princeton, “This school also just needs to do a better job hiring stem professors cause whewww [sic] some of these stem professors are problematic af and don’t give a fuck about addressing the academic barriers FLI students encounter at this institution.”

The high school advantage, though, can be present in any subject. Princeton hit a publicity gold mine in 2018 when Thomas and John “Newby” Parton ’18 — two then-undergraduates from disadvantaged backgrounds — won the Rhodes scholarship and Pyne Prize, respectively.

But my analysis of news articles and social media profiles shows that they’re the exception, not the norm. More often than not, Old Nassau’s star students have been raised in a world of advanced academics that gave them a head start in college. Graduates of elite high schools dominate the rosters of academic award winners.

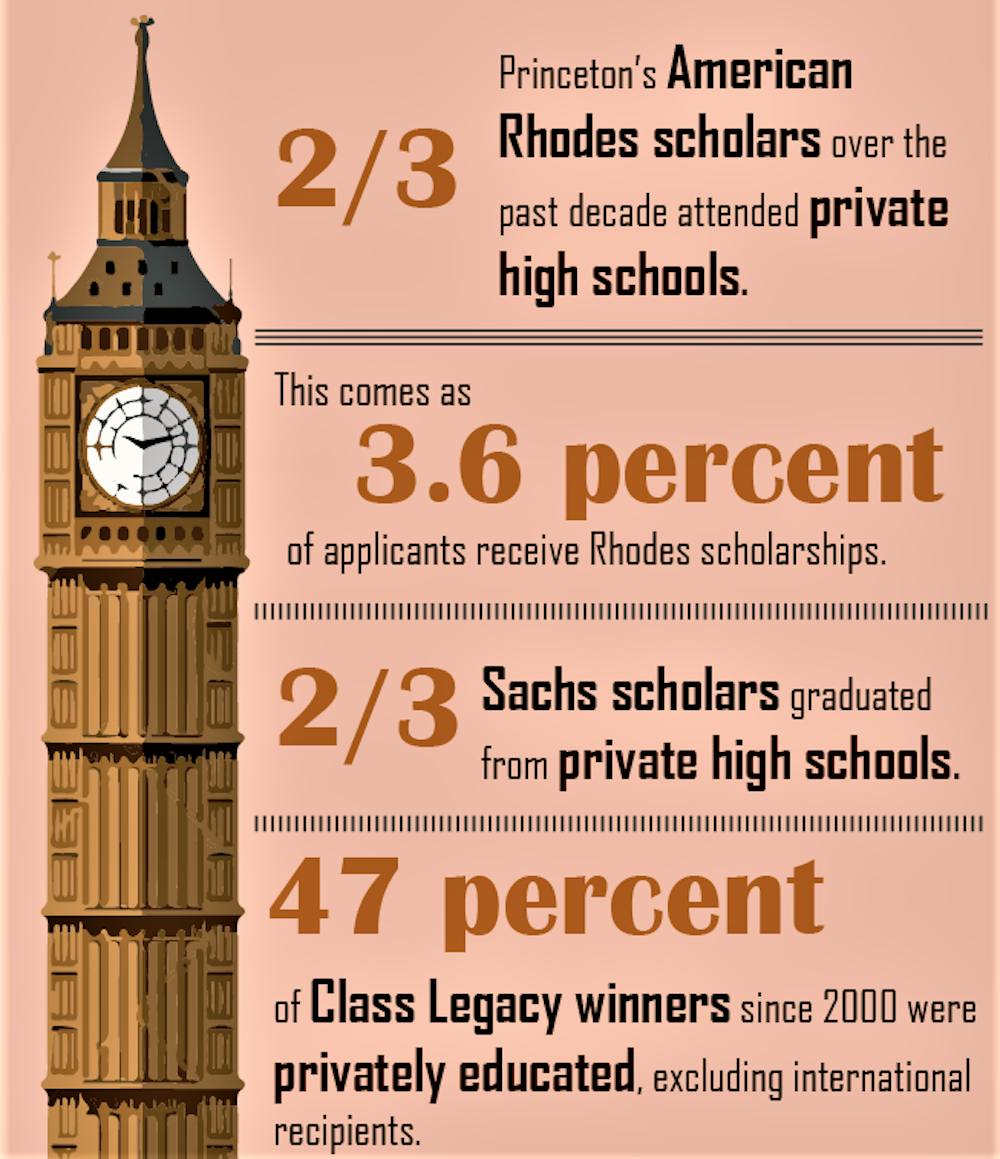

Two-thirds of the University’s two dozen American Rhodes scholars over the past decade attended private high schools. They included two graduates of Phillips Exeter Academy, one of Phillips Academy Andover, and a smattering of other high-profile names.

Nationwide, Exeter, Andover, and Choate Rosemary Hall alumni won two of the 32 Rhodes scholarships each in 2015, 2008, and 2016, respectively. That’s a remarkable feat for any high school, considering the award’s 3.6 percent acceptance rate. A 2010 analysis by the Association of Boarding Schools reported that boarding school graduates were 3,000 percent overrepresented among Rhodes scholars relative to the fraction of all American college students they contributed (though the statistical significance of their results is unclear).

Private school graduates also comprised two-thirds of Sachs scholars in the last decade. Public high school students were the majority of Marshall scholars. But most of their alma maters were magnet schools or located in the country’s wealthiest neighborhoods. Forty-seven percent of Class Legacy Prize winners since 2010 were privately educated. Their public counterparts generally came from magnet or affluent schools too.

Thomas admitted that it was difficult to motivate himself to take STEM courses at the University after coming from a struggling high school. The gap between him and his better-prepared peers was discouraging because he knew that he would be “disadvantaged from the start.”

“It’s exaggerated now that you’re at Princeton where — not only do people have a background and familiarity in these subjects — but in a lot of ways they were the best of the best in those subjects,” he said.

* * *

Distinctions between students’ backgrounds don’t — and probably shouldn’t — matter when they search for jobs. The corporate world generally looks for the most qualified people when hiring college graduates, setting aside networking. If Google needs a strong programmer or if Simon & Schuster requires a good editor, then they'll pick those with the best skills and credentials in these fields regardless of their backgrounds.

But there are plenty of competitive opportunities that don’t need a specific skill set. They search for people who can learn, adapt, plan, or use resources to develop their talents. The postgraduate scholarships — among other things — fall into this category.

A private school alumnus who aced linear algebra for a second time is less impressive than the underfunded public school graduate who advanced to topology after getting B’s from slogging through introductory classes. The committees that give academic awards should care about recognizing these differences for the sake of keeping themselves relevant. Selection criteria for almost every award that I’ve covered in my series have broadened their pools of potential applicants to keep pace with the ever-changing times.

For example, the Rhodes scholarship dropped its male-only requirement in the 1970s when colleges went to co-education. Half of last year’s winners were women. Matthew Stewart ’85 said that the Sachs scholarship adopted a “more open-minded view” of public service. The Pyne Prize now goes to two seniors instead of one to reflect the “larger undergraduate body and the greater diversity of its interests.”

But one criterion has remained unaltered throughout time: academic achievement. Marshall scholarship chairman Christopher Fisher said, “So far as I’m aware, the emphasis on academic distinction has been an enduring feature [of the scholarship].” It’s still defined across the board as earning mostly straight As, receiving honors, having a high class rank, and getting glowing recommendations from professors.

The problem is that most of these awards were created several decades or a century ago, back when colleges — especially elite colleges — were socioeconomically stratified. But the American education system has changed dramatically since then. Its developments have affected who goes to which colleges and if they become high achievers.

Magnet schools, incredibly advanced high school classes, and expensive tutoring services didn’t exist at the start of the 20th century. Princeton, Harvard, Yale, and their peers currently take many more of the nation’s highest-performing students than they used to. Secondary education is accelerating in wealthy enclaves. Almost everyone is smart and hardworking in the Ivy League schools nowadays, so students’ backgrounds play a major role in differentiating their academic performances relative to each other.

Awards — along with their scholarship and graduate school relatives — need to broaden their idea of what academic achievement resembles for each student. The best way to do this would be to ask for applicants to submit their high school transcripts and financial information about their families.

At the end of his book, Anthony Abraham Jack wrote that university policies should adopt an “[a]pproach that takes into account the constellation of institutions and influences that play a role in students’ strategies for negotiating their college years. I believe that we must examine students’ experiences in their neighborhoods and high schools, since these are ‘gateway institutions’ that fuel inequality.”

Higher education should heed his words in postgraduate decisions. Students’ pasts don’t disappear when they enter the ivory tower. The Rhodes Trust seems to already be making progress on this front judging by the diversity of their recent classes.

Undergraduate admissions already look at students holistically. They’ll rightly forgive applicants with slightly lower grades or fewer extracurricular activities if they came from underfunded high schools. The same benefit should be extended to them as they approach graduation.

Check out these other insights into winning awards.

This is the final article in a series examining the outcomes of academic awards.

Liam O’Connor is a senior geosciences concentrator from Wyoming, Del. He can be reached at lpo@princeton.edu.