Content Warning: The nature of the scholars’ research, and thus the content of this Q&A, concerns suicide.

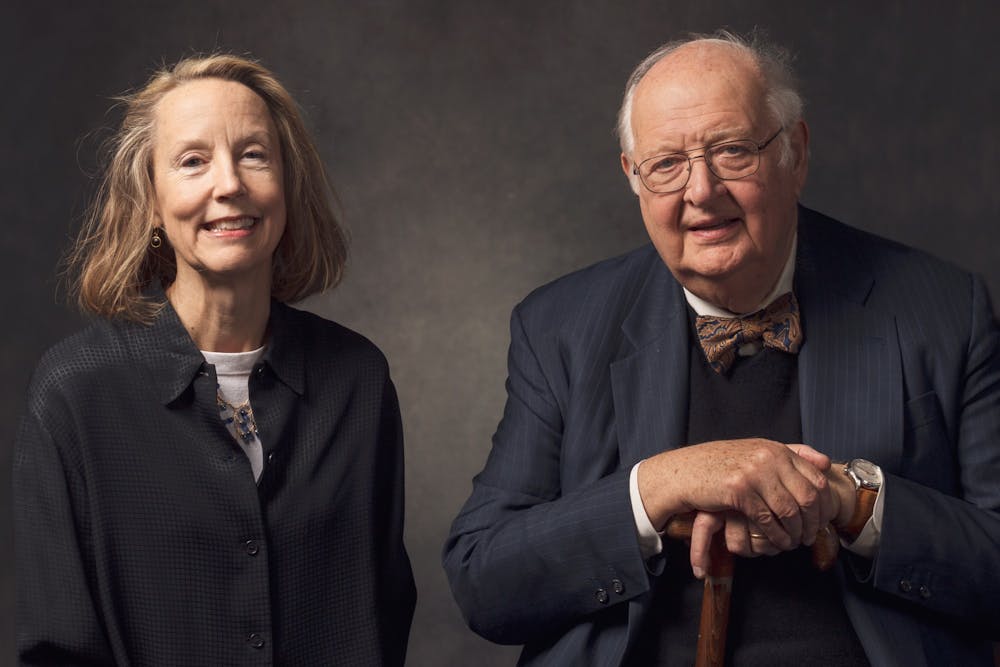

Anne Case is the Alexander Stewart 1886 Professor of Economics and Public Affairs, Emeritus, at the University, and Sir Angus Deaton — awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2015 — is the Dwight D. Eisenhower Professor of Economics and International Affairs, Emeritus. The two economic scholars — a married couple — recently released a book entitled “Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism.” Drawing on their groundbreaking econometric research on the subject, this text delves into the rise of suicides, drug overdoses, and alcohol-related deaths among white, middle-class Americans and how the economic system has allowed this to happen.

With their book talk originally scheduled for mid-March at Labyrinth Books canceled due to the impacts of COVID-19, Case and Deaton spoke with The Daily Princetonian over Zoom on Tuesday about their research and potential impacts of the pandemic related to their work.

This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

The Daily Princetonian: I was going to ask, just to start, where are you calling in from? And how are you holding up through all of this?

Anne Case: We’re home in Princeton, we live about three miles from Nassau Hall. And we go out a couple times a week to get perishables — and to walk a little bit outside — but otherwise, we’re mostly answering press calls. We were supposed to be on a big, complicated book tour that was going to take us, you know, to Europe and all over America, and a lot of that got reorganized to be podcasts and Zoom sessions. So, that keeps us quite busy, actually.

DP: Your paper entitled “Mortality and Morbidity in the 21st Century” found that middle-aged white Americans are increasingly dying from these so-called “deaths of despair.” And I know this obviously might be hard to do in a couple of sentences, but could you give [readers] some insight into how and why this phenomenon is occurring?

AC: The themes of the book are that capitalism in America today — now, this was written pre-COVID-19, but most of what we write still holds — capitalism in America today isn't working for people without a bachelor's degree. And that’s about two-thirds of adults in America.

What the book does is it first documents the kind of despair in the lives of people without a college degree. Like, we worry now in America that about 200,000 Americans could die from COVID-19 — which is a tragedy — but every year about 150,000 Americans die from suicide, drug overdose, and alcoholic liver disease year in and year out. We’ve documented underneath that there’s a lot of pain, rising mental health issues, family lives that have come apart, a loss of community. Then, we look to see what long term changes in the economy might have given way to those.

Angus Deaton: We think the fuel for this — or the lack of fuel for working class lives — has been a slow and steady deterioration in job prospects and wages. Recall, this is not the response to the recession. These stats were rising before the Great Recession, they rose during the Great Recession, they rose after the Great Recession … So this is something that’s unfolded for a very long time. I mean, the median wages for men without a BA [Bachelor of Arts] have been falling for nearly 70 years now.

DP: In a past Financial Times article about the research, Professor Case mentioned an outpouring of emails and letters you received from ordinary people recounting their losses after the publication of sort of the initial research paper. How did these messages come to inform your research and your eventual book?

AC: Some of them just thanked us — especially in the first piece — for talking about issues around which there's still an enormous amount of stigma. It’s very hard for people to talk about the fact that a loved one might have committed suicide. So to talk about the fact that this is happening on a very large scale, they found it really helpful.

Some of them talked about the fact that they don’t know their children — the mother of the children moved in with another guy, [the children are] living somewhere else — and so they’re hitting midlife alone without a solid family life. That also took us to the sociologists who’ve done a really good job documenting what’s happened to family, to community — the Andrew Cherlins, the Bob Putnams, the Sara McLanahans. And their research really informs what we did in our book.

DP: Sort of along those lines of family and community — and where we are now, in our homes — how do social distancing protocols and the state that the country is in right now fit into the narrative expressed in your book?

AD: It’s a little hard to tell.

Because, you know, social isolation is one of the risk factors for suicide. And as Anne was saying, some of the people who wrote to us are people who are very isolated within their own families … So one story about social distancing right now is that a lot of people may feel very isolated. A lot of people, for instance, who worked in the restaurant industry may have lost their jobs. They may have lost their businesses, and those businesses may never come back. So they might have thrived and found meaning in their lives and in the day-to-day business of running a restaurant or working in a restaurant, and [now] they find themselves alone.

… It’s also true that the places in America where there aren’t very many people have very high suicide rates. States like Montana or Utah, places along the Rocky Mountains where there are more animals than people, have very high suicide rates compared with say Princeton, New Jersey. … You could predict … that social distancing might be bad for suicide.

But you know, there’s another part of that story, which is that in wartime, when leaders forge a national solidarity against the common enemy, suicide rates tend to go down. You know, Winston Churchill is the classic example of that — suicide rates fell in Britain during World War II. People had a common purpose; they had real meaning in their lives. And if our leaders can do that now, maybe the same thing will happen.

AC: That takes you all the way back to [Émile] Durkheim, who wrote about suicide back in 1897. He is still kind of the foundation for all the work that is done on suicide, and he talks about social integration. If during a war you really do feel you’re part of a bigger enterprise, that can be protective. … We won’t know for a very long time how that will play out.

About businesses shutting down, again it’s way too early to know. The $2 trillion relief package that was just signed — more [of] that will certainly come — if those actually can protect small businesses, that might be helpful as well.

And as Angus was saying, all three of these things — suicide, drug overdose, alcohol-[related] liver disease — they were rising, there was this steady trend up, and you just can’t find the Great Recession in the trend lines. So we don’t know what this particular shock to the economic system will bring.

DP: You mentioned the $2.2 trillion spending bill. I was going to ask: what are your general thoughts on what you’ve seen from the federal government thus far?

AD: It’s too early to tell.

There’s been a lot of criticism too, that — you know, what happened in Britain for example was … the government effectively picked up the wage tab during the emergency. Whereas here, they relied on the unemployment system, and that doesn’t seem [as] good a solution as the British one. … But it’s really good to have some relief, for one thing, when people are really hurting and they need to be protected from the financial consequences of this. Otherwise, they’re not going to have enough to eat and so on. …

But one thing we really worried about: a lot of those people got dismissed last week — their health insurance probably runs out today because today’s the last day of the month. It’s not at all clear what’s going to happen to them. Two things are very worrying — one is that the President has said that testing will be free, but he hasn’t said that the visit to the emergency room to get tested will be free. Then there’s stories about people getting substantial bills from the emergency room — surprise medical bills or whatever — and their insurance says, “We’re not going to pay for that.”

Beyond that, if they actually get sick and [end] up in the hospital, you could have hundreds of thousands of people who finish up with bills of tens of thousands of dollars each, and that’s a very worrying thing. I think that’s going to — with a bit of logic — change our healthcare system.

DP: How would you describe what you’ve advocated for [on the issue of healthcare]?

AD: We’re very careful in the book not to advocate any particular set of reforms. There are lots of different models in Western Europe: from complete ownership of the healthcare system and the government runs as an employer of the national healthcare system, to other countries where it’s done through insurance and they’re very carefully regulated. So there’s lots of models to choose from, and all of those would be better than what we have.

AC: We need cost control. I mean, that’s the big thing, given that the healthcare industry has gone from being 5 percent of GDP in 1960 to 18 percent in 2019. That means that there’s just a lot less left for all other goods and services.

We think that the big thing here is going to be — there have been insurance companies in the last couple of days who will say that we’re going to waive the copays for people who have to go to the hospital for COVID-19. But the rub here is that private equity is buying up emergency departments of many, many, many, many hospitals. They do not accept insurance, and they charge what they want to charge. They’re going to actually pin as much as they can onto each individual to pay out of pocket.

AD: A lot of the people who’ve lost their jobs don't have any insurance anyway, so it’s not a question of copays. There’s no pay.

DP: With the current crisis in some senses exposing a lot of issues with the system, do you see that leading to any sort of substantive change? Or do you see that once this all blows over, us still being stuck in the same situation?

AC: It really depends. It’s way too early to know. We could go anywhere from people beginning to say this healthcare service doesn’t work for us and beginning to understand that the costs here are so high that you could bankrupt yourself having to go to a hospital with something like this. At the beginning of the crisis, people didn't want to test — that was before the announcement was made, the testing was free — so you think, “We're spreading this virus because people won’t even test right. So something’s definitely wrong here.”

From that extreme, we could go to the other extreme … If J&J’s [Johnson & Johnson’s] vaccine works, you know, here’s Big Pharma to the rescue. They could come out as heroes. And it may be the case that it makes it much harder to see reform. We have no idea where on the scale we’re going to end up.

AD: But things are going to be different for sure.

DP: A lot of the discussions surrounding these issues talk about and analyze a lot of federal, overarching policy. To what extent and through what means do you think these kinds of issues could be addressed on a more local scale?

AC: We still have a very bad drug epidemic in this country. One of the ways that the crack epidemic was brought to an end was because it was real community action. That was a local enterprise to make that happen. I think that with the current drug epidemic, community action is going to be incredibly important … One of the things we’ve talked about in great length in the book is that the loss of community in general puts these people at risk of feeling isolated.

Life might have been in a previous generation centered around a union hall and Friday nights there. The union halls are gone, and all of the community that came with them has disappeared.

AD: A lot of that local deterioration is because of much broader national or global forces. Like the rise of the super successful cities, where all the talented people go there, and they’re deprived of their voice in the communities that they came from … and so I’m not sure you can do much within the communities itself.

AC: It’s interesting because if you go back to William Julius Wilson, and what he wrote about what happened within black communities in the ’70s … As the Fair Housing Act took hold, and the most educated, the most respected members of neighborhoods were able to move into safer neighborhoods, that left a vacuum in communities in the inner cities. Currently, for the white working class, given that if people go away to college, they oftentimes don’t come back because there are no jobs for them where they came from. A lot of the talent is being taken out of those communities as well — it’s a real challenge.

DP: In all these discussions, whether surrounding the book or surrounding responses to the COVID-19 crisis, I was wondering where the two of you — as people who have co-written much of this research — disagree on some of the ways to address these problems.

AD: Maybe a little bit about education, but I don’t think we have a view. It’s something we tossed around between us.

I think the educational system’s not doing a very good job … some of that [can be resolved by] making it easier for people to go to college — not necessarily about free college, but by keeping down the cost of college. Some of that is that costs have been wrapped up by the cost of health care … but I think it's deeper than that. There are countries like Germany, for instance, where people do a lot of other things other than go to college and do very well and live very good lives that they are well prepared for by the educational system, in spite of not sending them all to college.

So that’s something we speculate a bit about in the book. But, we often just attach sort of straw men to each other — say, “You want everybody to go to college.” “You want no one to go to college.” But there’s no real disagreement.

AC: In the book, we try to get people to start to connect the dots between the cost of our healthcare system and what it does to the rest of the economy. The once-great state university systems have to increase their fees year, on year, on year. Why? Because the state budgets are being taken over by having to pay their share of Medicaid. So there’s a lot less leftover to help students within the state get a good four year education.

DP: Speaking about [those other countries]: In your research, the graphs are very stark when it shows the “deaths of despair” rising in the United States — this not being a worldwide phenomenon. Is it the health care aspect, is it education, or what other factors are at play that are making this seemingly such a sort of uniquely white American problem?

AD: Well, the two obvious factors are the incredible cost of health care, and how it’s paid for it. That's the first one. The second thing is the safety net here, which is much weaker than elsewhere.

On the other hand, it may be that America is just a precursor of what's going to come elsewhere. Less educated workers in all countries are at risk from globalization, the replacement by robots, and what have you. I don’t think other countries should think of themselves as being exempt.

DP: Do you have any sort of final message you wanted to say to anyone who reads this?

AD: Well, the message we might put out to all of your readers is to read the book. Labyrinth has lots of copies, even if you have to wait a month to get them.