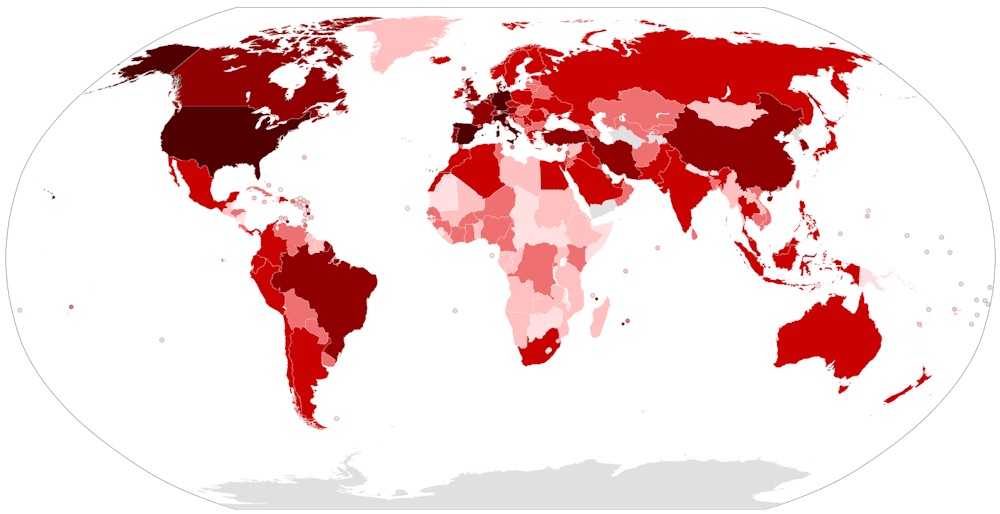

As the coronavirus pandemic wreaks havoc across America one reality has become clear: the virus is not the so-called “great equalizer.” Data from a small fraction of states reporting so far — including New Jersey — show that people of color are disproportionately likely to contract and die from COVID-19.

Many have sought to rally the nation by saying the coronavirus affects us all equally, that it does not discriminate on gender, race, class or any other demographic. But some communities are being hit harder than others. We have already seen how the spread of xenophobia and racism has resulted in verbal and physical attacks on Asian Americans.

Race also shapes the effects of the virus itself. COVID-19 does not spread in a vacuum; societal factors shape the path the virus takes, protecting some while leaving others exposed. Given the racial inequalities in American society, those most vulnerable tend to be people of color. In New Jersey, for example, black people comprise 24 percent of the confirmed deaths from COVID-19, despite making up just 15 percent of the state’s population.

The majority of states, however, are not reporting this data, creating a fragmented picture of the virus’s effects across the country. Even the states that are reporting have not collected race for all documented cases and deaths — Massachusetts, for example, only has information on the race of one-third of its COVID-19 patients.

On Tuesday, the federal government finally acknowledged these disparities when Dr. Anthony Fauci highlighted them in a White House press briefing. On Thursday, the CDC for the first time released data for hospitalizations by race in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. These numbers also point to racial disparities, as one-third of the hospitalizations were black patients. But this data, only including hospitalizations of 580 people in 14 states, remain insufficient for answering questions about access to care and the severity of the disease for different demographics.

In order to build a nationwide understanding of who is most vulnerable to the virus, and craft an effective strategy to defeat it, the federal government must track and release racial data on testing, cases, and deaths in all 50 states. Data on these key figures will allow us to see disparities in who has access to testing, who has contracted the disease, and who is experiencing the most severe consequences.

Recognizing this, members of Congress have pressured the federal government for all three types of data. New Jersey Senator Cory Booker, along with Democratic colleagues Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, Ayanna Pressley, and Robin Kelly, wrote a letter to this effect to Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar, highlighting the urgency of collecting this information.

Indeed, access to this centralized data will allow policy makers and health care workers to target those most vulnerable to the disease, helping us effectively combat its spread. Take for example Milwaukee County, Wis., which started tracking racial impacts of the coronavirus early. After finding that black people, who make up 28 percent of the county’s population, constitute about 50 percent of cases and 73 percent of deaths, Milwaukee started testing residents in majority-black neighborhoods at twice the rate of majority-white areas, allowing them to work more efficiently on containing the virus.

Such targeted strategies, made possible by specific racial data, are essential. In a pandemic like the coronavirus that has the ability to spread rapidly and easily, nobody will be completely safe until everybody is; it won’t end anywhere until it’s ended everywhere. Just as initial information that older people are especially susceptible to the coronavirus compelled an approach centered on protecting them, understanding the racial disparities in the spread and effect of the virus can bring the focus to other vulnerable populations as well.

It is not hard to determine what makes racial minorities in America more vulnerable to COVID-19. A myriad of persisting inequities in the criminal justice system, housing and labor markets, and the healthcare system all create the racial disparities that are exacerbated by this pandemic.

Many of the most basic recommendations from epidemiologists for containing the virus are themselves privileges. Social distancing is not an option for everybody, for example. This is most obvious in jails and prisons, where people of color are disproportionately represented. Isolating from others can be impossible, as in the case of the Federal Correctional Complex in Oakdale, La., and the potential catastrophe on Rikers Island in East River, N.Y. The Cook County jail in Chicago, Ill., is now the largest known source of coronavirus infections in the country with over 350 confirmed cases among inmates and staff, the majority of whom have not even been tested.

Not everyone can adhere to recommendations to work from home either. People of color are more likely to work in service sector jobs that require them to risk their health by continuing to go into work. These workers, including employees at companies like McDonald’s and Amazon, have spoken out about the lack of safety and protection they feel at their jobs.

Even if they are able to stay home, inequities in housing create another point of vulnerability for people of color. As a legacy of redlining and the racial wealth gap, black people are less likely to own their own homes. Crowded, multigenerational living environments increase their contact with others compared to people living in single-family homes, creating the potential for more spread.

This applies not only to low-income people of color, but affluent people as well. Middle- and upper-class black people are more likely to live in high-poverty areas than even lower-class white people. This correlates to less access to resources such as quality grocery stores, forcing people to travel farther (including on public transportation), and increased distance from trauma centers, making it harder for people to get the treatment they need if they do contract the coronavirus.

This legacy of housing segregation that has confined black people and other minorities to less desirable neighborhoods has also led to inequities in exposure to pollution, as companies have targeted these areas to place factories and other polluting facilities. A recent EPA study found that people of color are more likely to be exposed to harmful pollution in the form of particulate matter. Exposure to pollution causes, among other conditions, an increased risk for asthma and chronic lung disease.

Not only do these existing factors mean black and brown Americans are less healthy than whites, but inequity within the health care system itself means minorities are less likely to receive quality care for these conditions, in part because they are less likely to have health insurance than whites. Individual racial biases play a role in this pandemic as well: initial analyses show that Black patients are less likely to be referred for testing when showing symptoms of COVID-19.

As a result of historical discrimination in medical care — most infamously exemplifed by the Tuskegee Study — African Americans are, understandably, less likely to trust the health care system altogether, further perpetuating disparities.

Given these inequities, it comes as no surprise that minorities are more likely to suffer from health conditions like asthma, diabetes, and heart disease, that make people more susceptible to experience severe illness and dying from coronavirus. Indeed, the CDC data shows that ninety percent of those hospitalized had underlying medical conditions. Moreover, a study released this week that found a link between exposure to air pollution and increased death rates from COVID-19 provides a concrete example of how worse health conditions are leading to racial disparities in the effect of the coronavirus.

From less ability to adapt to the dangers of the pandemic to existing health inequalities that make them more susceptible to more severe cases of COVID-19, people of color are uniquely vulnerable to the coronavirus.

The truth is that this pandemic is not hitting all people the same way. We need policy to match that reality. Access to data on the disparate racial impact of coronavirus will not only allow the government and healthcare workers to more effectively fight this pandemic, but will place into sharp relief the devastating consequences of the underlying racial inequalities in our society.

As we eventually negotiate the aftermath of this crisis, this data should be a moment of reckoning that motivates reparative and preventative measures to support the health of people of color, pandemic or not.

Julia and Shannon Chaffers are sophomores from Wellesley, Mass. They can be reached at chaffers@princeton.edu and sec3@princeton.edu, respectively.