For most sophomores, Street Week in February determined their eating future for their remaining years at Princeton. 93% of those who participated were placed into their first or second choices, and all students who applied were granted a spot in an eating club. Plus, students received a $200 incentive to join from the University.

A growing minority on campus, however, chooses not to participate in Street Week, instead throwing their hat into the ring of five co-ops on campus, who held their member draws over these past two weeks. Co-ops have been rapidly growing in popularity, both for their affordability and their ability to build a rare sense of tight-knit community not found in the residential colleges or other campus spaces.

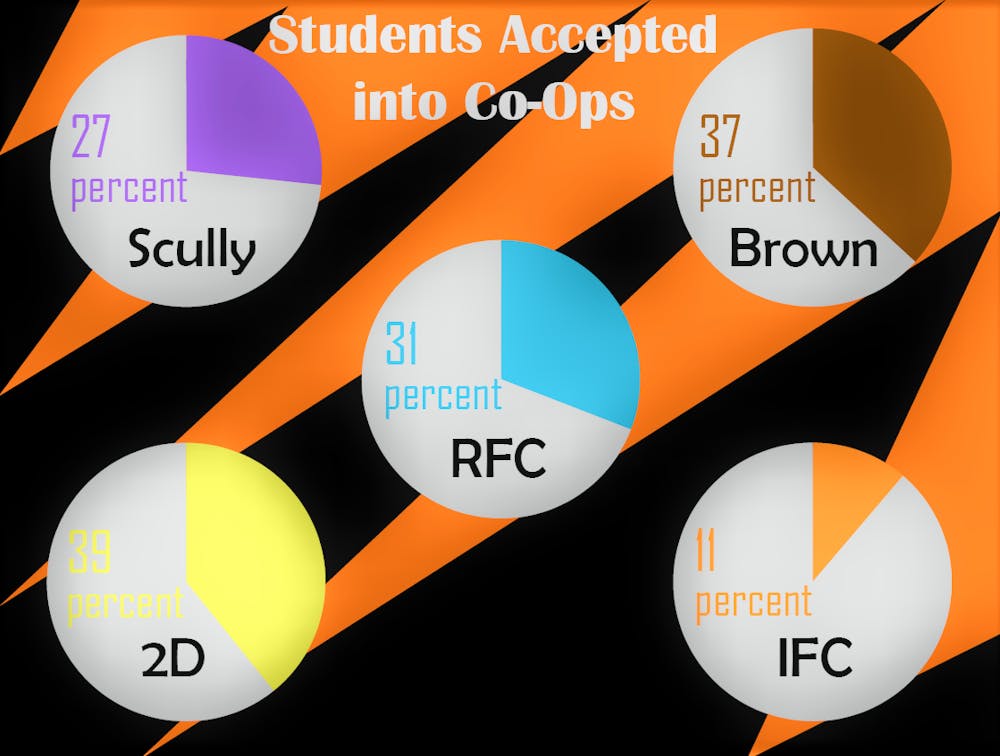

Unlike with the eating clubs, not everyone was able to get a co-op spot. On average, co-ops this spring could accept only 29% of the students who applied due to a lack of space, based on figures I gathered from interviews with each co-op leader. All five co-ops use a random lottery system to prevent the feeling of exclusivity that bicker communicates, yet a combined waitlist for all these lotteries would number in the hundreds. This is unjust, and the University needs to begin addressing this demand by ensuring that 100% of co-op applicants receive a spot, as was the case with the eating clubs this year.

I was one of the lucky ones. After a stressful weekend when I learned I hadn’t gotten a spot in four of the five co-ops, I spent the next week praying for a spot in the fifth co-op – 2 Dickinson, or “2D” (who held their draw at a later date). This past Wednesday, I was elated to learn that I had gotten a spot in 2D, but my joy quickly faded as I realized that many of my friends who were also seeking co-op spots may not end up being as fortunate as I had been.

It is time for a change in Princeton’s co-op policy. In the past, the University has gradually added co-ops one at a time, driven by student-led petitions. This is clearly not sufficient to meet the growing demand, especially given the University’s intention to soon increase the size of the student body. Instead, Princeton must begin creating sufficient space for the volume of interested students by adding more co-ops to fill the growing need.

One concern that has come up from the administration has been available kitchens. Yet the University has been able to gradually meet the demand for co-ops in the past. Surely with the money that this University sinks into the residential college system, they might consider apportioning some of those resources toward building and renovating more kitchens. After all, co-ops provide as much, if not more, of an enriching experience as the residential colleges, and certainly a more genuine one. Or take the money being sent toward eating club subsidies ($200 to each sophomore for joining) and send it toward co-ops!

Iris Samuels ’19, who wrote a column in 2016 calling for more co-ops, suggested that the seven additional buildings (currently used for graduate student housing) that the University owns on Dickinson Street, University Place, and Edwards Place could be converted into co-ops. There is also an opportunity in the new residential colleges and environmental studies complex being built – why not add more kitchens and co-ops to those?

A good first step for helping independents in general could be privatizing all kitchens in upperclassmen housing, adding prox entry like the kitchens in Pyne and Lockhart (the ‘Prince’ Editorial Board actually argued for this back in 2017). This ensures that the kitchens are not vandalized by drunk or otherwise uncouth upperclassmen while fostering a greater sense of accountability among kitchen users. Any student could apply to get access to their dorm building’s kitchen, as long as they sign a contract and agree to keep the space clean. Another opportunity to integrate co-ops into the campus fabric could be to establish meal exchanges among eating clubs, dining halls, and co-ops.

Other universities have robust and successful student-run co-op systems, including Stanford. Unfortunately, the University has been moving backward. Instead of institutionalizing the informal food-share community that had evolved in the Pink House, the University chose to tighten the house’s room draw process (limiting it to only Forbes members) and discourage the food-share. The failure of the Charter co-op proposal, while not technically under the purview of the University, was still a significant blow to students seeking more space for co-ops. If the University continues to ignore the growing interest in and demand for co-ops, they will find increasing cases of dissatisfaction, poor mental health, and unnecessary stress among its students.

Figuring out my eating situation has been one of the most challenging experiences of my sophomore year – and all because I did not want to spend thousands of dollars on an elitist eating club experience. To quote Samuels, “food should never be a source of so much stress, planning, and scheming.” I am dismayed at how difficult the University has made it for students to eat in alternative situations, and I strongly urge University administrators to pay more attention to the growing co-op crisis.

Claire Wayner is a sophomore studying civil & environmental engineering. She can be reached atcwayner@princeton.edu.