Last month, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, an over $2 trillion stimulus package that provides direct financial assistance to American citizens and legal permanent residents, entered into effect. Though they pay billions of dollars in taxes annually, undocumented immigrants will not receive a cent.

For one father of four who has lived and worked in Princeton for 20 years, this reality is deeply unfair.

“Like many people who came as immigrants, we are struggling because we give as much as we can to this country — through work, through paying taxes,” he said in an interview conducted in Spanish. “It doesn’t seem fair to me that they are helping the people who are here legally, and we cannot receive the same help.”

“No me parece justo,” he said. “It does not seem just.”

The man, who spoke to The Daily Princetonian under the condition of anonymity, is an undocumented immigrant from Mexico. He and his wife, also undocumented, were recently laid off and are now out of work. The two have been keeping busy as they care for their children, but they feel increasingly stressed and desperate not knowing how long the crisis will keep them both out of work.

These anxieties are not exclusive to the undocumented community; a record-breaking number of New Jersey residents have filed for unemployment insurance as a result of the pandemic. But for undocumented immigrants, who lack access to unemployment benefits, Medicaid, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and various other governmental programs, making use of federal and state social safety nets is not an option.

The father who spoke with the ‘Prince’ has four children, all of whom are United States citizens. Their parents’ lack of legal immigration status, however, prevents them from being able to claim a CARES Act payout.

“It’s outrageous that the government isn’t helping everybody,” said Veronica Olivares-Weber, Vice-Chair of the Princeton Human Services Commission. “Obviously, this is not new, but I can’t believe that even during this crisis there is no help for them.”

“During this time, immigration status shouldn’t matter,” she added.

Americans remain divided on the question of whether it should.

In a March poll conducted by USA Today and Ipsos, a market research company, 40 percent of respondents said they were in favor of the government providing temporary financial help for undocumented immigrants unable to work, while 42 percent of respondents opposed the measure.

The divide also falls somewhat along partisan lines, with 58 percent of Democrats supporting such a measure and 70 percent of Republicans opposing it.

Thus far, California is the only state to budget disaster relief for undocumented immigrants — Gov. Gavin Newsom announced a $125 million fund last week. A group of 70 immigrant and labor advocacy organizations also sent New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy a letter urging action on the matter, but no economic relief legislation has been passed.

While Gov. Murphy’s moratorium on evictions and foreclosures has provided some security for New Jersey’s estimated 526,000 undocumented immigrants, Olivares-Weber said this is only a short-term solution since the measure will only last until 60 days after the end of the state of emergency. At that point, landlords will expect payment.

“What people don’t think about is, what is going to happen in three months?” Olivares-Weber said. “The landlord is going to come and say, ‘Pay me back. You owe me for these three months.’”

Undocumented families whose adult members are currently out of work may not have that kind of money available. The father who spoke with the ‘Prince’ had been living paycheck-to-paycheck since before the pandemic began. Facing a sudden loss of household income and with no savings to fall back on — not to mention New Jersey’s “stay at home order” preventing him from leaving the house — he has no means of producing several months’ worth of rent.

Some local organizations have stepped up, however, to address issues like this.

Princeton Children’s Fund’s (PCF) Coronavirus Emergency Relief Fund (CERF), established on March 16, will allow Princeton residents or individuals with children in Princeton Public Schools to apply for emergency housing assistance regardless of their immigration status.

The municipal government, which has been formally recognized as a “Welcoming Community” since 2015 and historically taken liberal positions on immigration issues, has supported this effort.

PCF has partnered with the Department of Human Services and several other local non-profits. According to their website, PCF will consider expenses such as rent, utilities, childcare related to “essential employee” status, and non-medical devices and accessories lost due to COVID-19. Working with Princeton Community Housing and Housing Initiatives of Princeton, organizers have been communicating with landlords and paying them directly.

Olivares-Weber said that despite being hit by hard times themselves, many of these landlords have been helpful, in many cases reducing the cost of rent.

While this emergency fund is focused on housing assistance, several other local organizations have been partnering to provide food to community members. The municipality website contains a delivery schedule for the eight different organizations providing food assistance, and Director of Human Services Melissa Urias has been working to coordinate their efforts.

Local non-profits like Arm in Arm, Meals on Wheels of Mercer County, and Share My Meals are providing general food assistance. In addition, the Mercer County Nutrition Project for Older Adults is providing food for Princeton’s senior citizens, Jewish Family and Children’s Services has been running a Mobile Food Pantry, and Princeton Public Schools have been delivering “five days worth of breakfast and lunch” weekly for children who qualify for free and reduced lunch programs.

And where individuals might fall through the cracks, informal groups of volunteers are stepping in. Maya Aronoff ’19, now a graduate student in the Woodrow Wilson School, said that she has been working with several other students and local organizers to fundraise through social media, as they seek to provide relief to undocumented individuals.

“Everybody’s kind of pulling out all the stops,” she said.

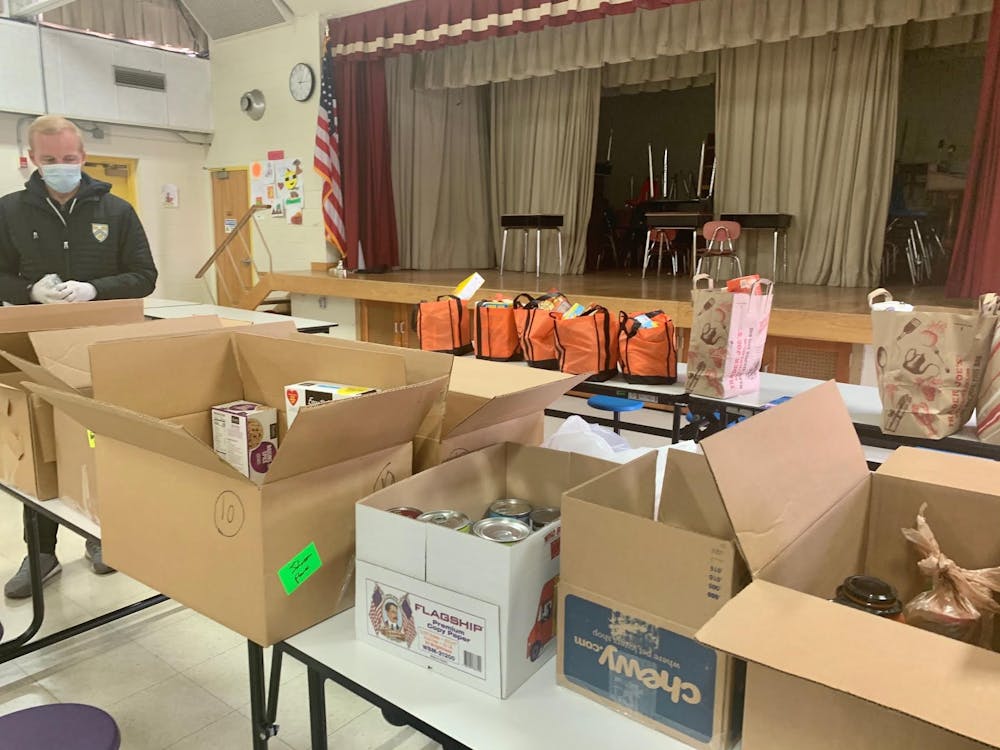

Last week, following a Venmo-request campaign on social media, Aronoff and others were able to purchase and deliver food directly to 32 undocumented day laborers living in Princeton.

Lukas Althoff, a graduate student in the economics department, helped Olivares-Weber pack and deliver the food.

Photo Courtesy of Veronica Olivares-Weber

The father who spoke with the ‘Prince’ said he greatly appreciates the community’s efforts. He and his family have been receiving food deliveries through Arm in Arm, and he said that the Emergency Fund has already helped him with one month’s rent. Despite wishing that the federal and state governments would do more for undocumented immigrants during this economic crisis, he said he feels supported locally.

“In this crisis, we’ve encountered so many people who have wanted to help us, and we are thankful that we have found people who can help us moving forward,” he said.

“Gracias a Dios,” he added. “Thank God.”

One of the biggest challenges for the organizations providing aid has been getting the word out, with many Princeton residents staying at home. The municipality has relied heavily on social media, posting videos in both English and Spanish to explain where to apply for housing assistance and how to donate to other programs.

Some organizers have also utilized less formal channels: WhatsApp groups and Facebook Messenger. The father who spoke with the ‘Prince’ does not speak English and said he found out about the program through one of his kids’ school teachers.

“We thank God that there are people who are able to get us the information we need in our own language,” he said.

Olivares-Weber, who herself spoke only Spanish until she was 22, is active in the town’s Hispanic community. She teaches art classes at the Henry Pannell Center, where around 80 percent of the students in her class are Latino, and she said that many of their parents call her directly when in need of assistance. She said she gets at least five phone calls a day from Spanish-speaking residents asking how to receive assistance from the municipality.

“Or even via Facebook, I get messages like ‘Oh, Señora Veronica, I’m looking for help,’” she said. “We have different channels and different people who have been active in the community who have been able to communicate.”

While the Human Services Department does not traditionally have trouble getting the word out to families with children, Olivares-Weber said it is somewhat more difficult — but no less important — to reach many of the undocumented single men in the community who work as day laborers and are generally rehired and paid on a daily basis. For the people the Department has a harder time reaching, nonprofits have helped fill in the gaps.

Unidad Latina, a Mercer County-based advocacy organization, started its own fundraising campaign with the goal of raising $10,000 to assist day laborers in Princeton. University students including Aronoff have contributed to the effort.

“Day laborers have been one of the sectors most affected by this crisis,” said Jorge Torres, an organizer for Unidad Latina. “And they support the local economy tremendously.”

According to Torres, who was undocumented for nine years before becoming a U.S. citizen, 100 percent of funds raised will go directly to the day laborers.

Thus far, Olivares-Weber said several day laborers in town have already applied for PCF funding. But for workers who are especially wary of contacting the government, Torres said the Unidad Latina fund will provide less formal relief. Though the local government does not enforce immigration law and limits cooperation with Immigration and Customs Reform (ICE) in accordance with New Jersey’s Immigrant Trust Directive, Torres said there is still an unavoidable sense of fear among some local immigrants — who particularly fear being detained after ICE confirmed 16 cases of COVID-19 within New Jersey detention centers.

In some cases, deliberate deception feeds into that fear. Last month, Police Chief Nicholas Sutter and Councilwoman Leticia Fraga released videos in English and Spanish debunking rumors of a “national guard deployment” after many Princeton residents had received robocalls, emails, and text messages in a “deliberate misinformation campaign” targeted at the immigrant community.

Aware of this anxiety, the Human Services Department has attempted to communicate with undocumented residents as much as possible to proactively halt the spread of misinformation.

“I got a WhatsApp from one of the families saying, ‘Señora Veronica, is it true that we’re going to have to get inside because five helicopters are coming to spray disinfectant all over town?’” Olivares-Weber said. “What I keep telling the people is that you need to check our social media. If you hear anything you haven’t seen in the news or it’s not in the social media of the municipality, it’s not true.”

Olivares-Weber has also been in communication with Torres and Aronoff, figuring out how to ensure no Princeton residents fall through the cracks.

“We are trying so hard to get everybody to apply,” she said. “I was telling Maya [Aronoff] ‘make sure you guys give all the information to them, for those people who haven’t applied,’ and we keep asking them to do that.”

Torres has been amazed by the sheer number of local efforts.

“All help is good right now ... The more we have the better,” he said. “There has been incredible solidarity among movements and among communities across sectors.”

Unlike PCF or Human Services Department, Unidad Latina is also a political advocacy organization — one of many nonprofits that must now balance campaigning for long-term policy change with providing immediate assistance.

In some cases, the two goals may come into conflict. Organizations have accordingly sought to commit funds to short-term, urgent relief projects while also emphasizing the inherent inadequacy of short-term solutions. On April 7, when the Princeton-based Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) committed $50 million to relief organizations across the state, the organization’s President and CEO tweeted that the pandemic “shines a light on the incredible inequity in our society” and that their organization will “provide aid now while continuing to focus on long-term policy change.”

Likewise, a central portion of Unidad Latina’s mission involves organizing and advocating for the civil rights of the migrant community. Their website notes, “there is no reason immigrants should be excluded from obtaining protections, medicine, and services in a global pandemic.” But until their vision becomes reality, Unidad Latina is urgently raising funds.

On the question of whether the pandemic will lead to policy change, Aronoff said she is a “realistic optimist.” While she believes there is a slight chance this crisis changes how Americans “think about what government owes society and what community members owe one another,” she said that socioeconomic disparities in COVID-19’s impact may inhibit progress.

“If you are wealthier and able to work from home, you might not — well quite literally, you’re not going to see the effect on people who are in total crisis right now,” she said. “Social distancing sort of exacerbates the ways in which people with more power might not see those disparities.”

Torres was more hopeful, saying the current situation could spark productive conversations around healthcare, education, and immigrant rights. Though the nation is divided on whether and how to provide undocumented immigrants support during the pandemic, Torres has been encouraged by what he has seen locally.

He said he views the help that Princeton community members of various races, ethnicities, and occupations have given one another as cause for optimism.

“I have seen students helping day laborers … and just people being all-around involved,” he said. “The virus in some ways has unified us.”

In the past, Olivares-Weber was involved with the Latin American Legal Defense Fund (LALDEF), a Princeton-founded and Trenton-based group of immigration advocates, and she wishes she could continue that advocacy now.

“I feel really bad that I’m not able to focus on that at the moment, but to tell you the truth I’ve been focusing on my community — on the people that I know, on the children that live here and go to the same schools as my 16-year-old,” she said. “They are our neighbors, and my focus right now is on them.”

As more people apply for PCF funding each day, Olivares-Weber said she remains dedicated to one goal: ensuring that all Princeton residents can pay their bills.

“I just really need to focus on these applications. I just want to approve them all,” she said. “That’s the only thing I want to do.”

Editor’s Note: This piece has been updated to remove some information that could not be independently verified.