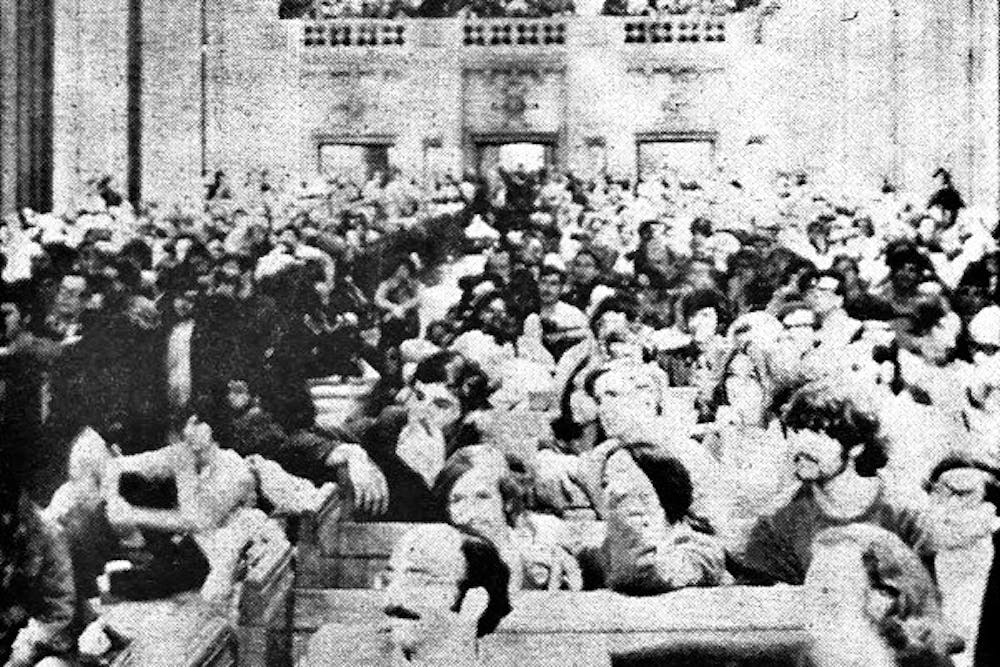

Fifty years ago tonight, more than 2,500 students and faculty thronged into the Chapel, enraged by President Richard Nixon’s 9 p.m. announcement that U.S. troops had deployed to Cambodia. By the time a bomb threat forced them to evacuate two hours later, those present had voted to “strike immediately against all academic and social functions of the university.”

On that dramatic evening — which, like today, fell on a Thursday — students wrestled with a war they considered immoral and illegal. For many, the draft loomed. Students soon launched a campus strike that would last through Commencement. On May 2, 1970, four people, including two University students, firebombed the ROTC Armory on Washington Road. Princeton had reached a crossroads.

The spring of 1970 resembles our own historical moment in unsettling yet instructive ways. Though we often imagine Princeton as a cloistered paradise, the University is, and has always been, imbricated within the world. Indeed, it was in May 1970 that Nassau Hall permanently opened FitzRandolph Gate, “in a symbol of the University’s openness to the local and worldwide community.”

That events around the world affect Princeton reveals our collective precarity. As COVID-19 has made all too clear, we are liable to disruption and dispersal, just as our forebears were half a century ago. But our campus community is precious precisely because it is fragile. If we recognize this truth, we can build a Princeton that withstands even the most ferocious of storms.

In 1970, urgent debates about the Vietnam War and racial injustice shattered the idyll of campus. On Monday, May 4, nearly 4,000 students and faculty packed into Jadwin Gymnasium, where they weighed how to enact the strike approved in the Chapel three days prior.

John D. Semida ’72 challenged his peers who ignored racial oppression in the United States, even as they opposed war in Vietnam and Cambodia. “The only way anything can be stopped abroad is to stop things here,” he declared. “A student strike is nothing. This institution must make a stand and must defend the stand.”

After four hours of heated deliberation, the crowd voted that, “as an institution,” the University had no choice but to “oppose the Cambodian invasion, American foreign policy and domestic oppression.” The same day, the Ohio National Guard shot four students dead at Kent State.

Concurrently, the faculty announced that students on strike could waive or postpone their spring academic work. In a decision that resonates today, pass-fail grading became available for all courses. The faculty further granted students two weeks of leave in the fall, allowing them to participate in electoral campaigns. In October 1971, Princeton held its first fall break.

In 1966, a student writing in The Daily Princetonian lamented that his peers treated Princeton as “a four-year sabbatical from responsibility and concern.” Four years later, the graduating class traded in caps and gowns for red armbands, called off its Class Day, step sing, and senior prom, and boycotted the P-rade. They successfully petitioned the University to disband Navy ROTC, which wouldn’t return until 2014.

As Valedictorian Raymond Gibbons ’70 reflected at Commencement, “any apolitical farewell address delivered on this occasion would be a peculiar anachronism.”

Yet, within a few short months, the turmoil evanesced, as students all but exhausted the fervor that had inspired them to protest. In June 1971, the ‘Prince’ reported that “a new apathy” had descended upon Princeton, “an emotionally burned out university, whose chief attribute was disillusionment.”

Fifty years later, we risk once again forgetting the lessons of 1970. Before COVID-19 metastasized into a pandemic, I watched many students, including myself, take Princeton’s proverbial immunity as a given.

On March 10, the day before most students learned they would have to return home, an anonymous student wrote on the Facebook page TigerConfessions++, “Everyone who is getting mad at seniors for being upset and calling them inconsiderate — we didn’t go through 3 years of bullshit for mfkn CORONA WHICH IS THE MFKN FLU to fuck everything up. I’m so sick of everyone panicking including a multi billion dollar university.”

Though I understand my peer’s frustration, the post reveals a pernicious entitlement, which threatens to warp our collective perspective. The student urged Princeton to turn its back on a world in crisis, to carry on with business as usual. In their view, a university as wealthy as ours had no right to “panic.”

Tonight, the Chapel sits empty, a stark coda to a movement that began 50 years ago. Yet, we now have another chance to understand our institution’s place within the world. The privilege of attending Princeton compels us to lean into, rather than shirk, global challenges and responsibilities. Did we really think an endowment of $26.1 billion would inoculate against coronavirus?

In an uncertain world, our community is not to be taken for granted. Nor is it to be accepted uncritically. If our four years at Princeton are to be more than a sabbatical, we must first realize that a fragile community requires our utmost care.

Jonathan Ort is editor-in-chief of The Daily Princetonian. He can be reached at eic@dailyprincetonian.com and on Twitter at @ort_jon.

Read James Anderson’s coverage of the spring 1970 campus protests here.