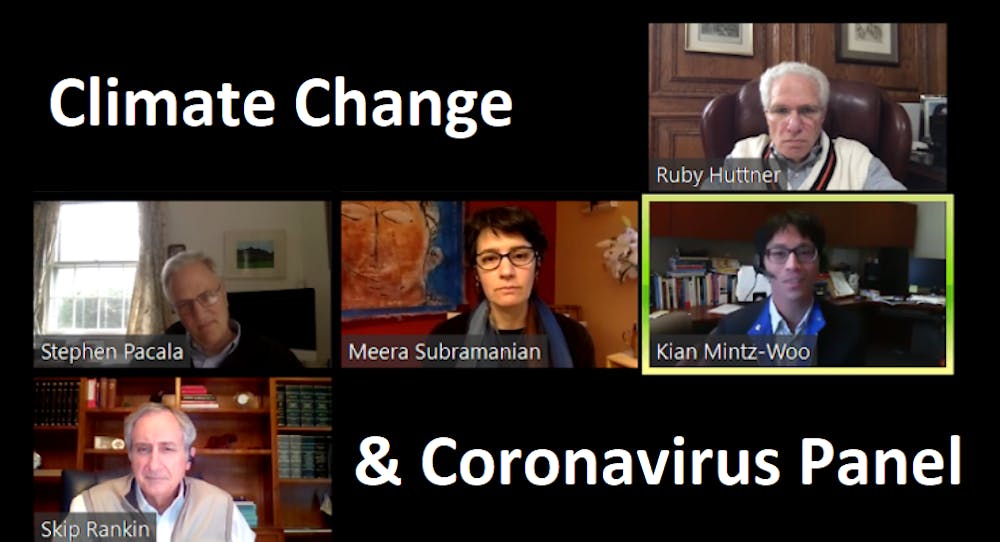

The Princeton Environmental Activism Coalition, the Princeton Environmental Institute (PEI), and the Pace Center for Civic Engagement hosted a discussion on environmental policy in the age of the novel coronavirus on April 24.

While the panelists acknowledged the pandemic’s severity, they remained optimistic about its potential to catalyze sustainable infrastructure changes and policies such as carbon pricing to combat the climate crisis.

Stephen Pacala, the Frederick D. Petrie Professor in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and co-director of the University’s Carbon Mitigation Initiative, began by highlighting the importance of civic engagement.

In a time of increasing environmental rollbacks due to the pandemic, Pacala reminded the audience to vote in upcoming elections and pay attention to any upcoming infrastructure stimulus packages

“This is the time to get the infrastructure [of the energy system] to go to a net-zero energy economy,” he said.

He noted that the dramatic decrease in the price of wind, solar, and lithium ion batteries in the last 10 years has made it possible to build a non-emitting energy system that operates at about the same price as the current one. With a government infrastructure program to cover the capital costs of the energy system, the task of reaching net-zero carbon by mid-century becomes dramatically more feasible.

To create a bipartisan coalition for such a mandate, Pacala points to the large economic incentive for red states to adopt renewable energy. Solar energy, for example, “would be dominated in the southern states,” he said.

Adding on to the call for the government to consider environmental effects, Kian Mintz-Woo, a postdoctoral research associate at the University Center for Human Values and PEI, said that now, during the COVID-19 crisis, “is the time to implement carbon pricing policy.”

He described two types of carbon pricing policies: a cap-and-trade act and a carbon tax. They both aim to increase the costs companies incur by emitting carbon. Mintz-Woo addressed consumer concerns about these policies.

“Most studies find that carbon taxes in rebates would make the lowest 60-80 percent of society overall better off,” Mintz-Woo said.

According to Mintz-Woo, now is the best time to implement a carbon tax, especially because pandemic-induced negative oil prices would make doing so less damaging to consumers.

“If you were to say filling up is $1 a gallon, adding another 25 cents for a carbon tax would be much easier to stomach than under normal circumstances, where it would be more like $3 a gallon,” Mintz-Woo explained.

In addition, Mintz-Woo said that the reduction in travel that could result from carbon pricing on the travel industry, which carries a large carbon footprint, would bring health benefits. Less travel would mean slower COVID-19 infection rates.

An audience member questioned how carbon pricing would affect an already struggling airline industry. Without denying the harm a carbon pricing policy would have towards carbon-intensive industries, Mintz-Woo stressed the importance of building safety nets for people who lose employment through holding job retraining programs for less carbon-intensive positions.

“The amount of employment that’s associated with solar is far larger than that associated with legacy fossil fuels,” he said.

Mintz-Woo also explained the unique ways in which COVID-19 has affected market demand. Under normal circumstances, the introduction of carbon pricing would increase prices and reduce demand.

“But in the current situation, where demand is so low,” Mintz-Woo stated, “[carbon pricing] would lower the level of demand that we would return to.”

In other words, enacting carbon pricing policies during the pandemic would allow for a new normal post-COVID, during which U.S. emissions rates would continue to stay lower than the pre-crisis level.

The last speaker, Meera Subramaian, a Visiting Professor in the Environment and the Humanities as well as the president of the Society of Environmental Journalists, addressed how journalists are trying to “shift the narrative” to shine the spotlight on “the unfair impact” COVID-19 has had on minorities and working-class Americans, who also disproportionately feel the effects of climate change.

Despite their similarities, Subramaian is careful to distinguish the two crises. She notes COVID-19 is not an effect of climate change. Rather, the two events are related in “how humans deal with crises, what kind of response we give them, and how we conceptualize...long term risks,” Subramaian said. “It also brings into the equation how we understand science, and how we understand experts, and whether we listen to them.”

In an effort to make the event accessible to the public, the conference organizers, Hannah Reynolds ’22 and Mayu Takeuchi ’23, live streamed the event on Facebook and uploaded a recording on YouTube.

“We had over 200 attendees (through Zoom and Facebook livestream), hailing from around the world!” Takeuchi said, who noted that audience members tuned in from Trinidad to India to Peru.

Reynolds expressed gratitude for the opportunity to collaborate with Ruby Huttner ’72 and Clyde “Skip” Rankin ’72, the Princeton alumni who moderated the conversation.

“I enjoyed being able to share this event beyond just the student body,“ she said. “Alumni who haven’t returned to Princeton in 50 years ... logged on for this event.”