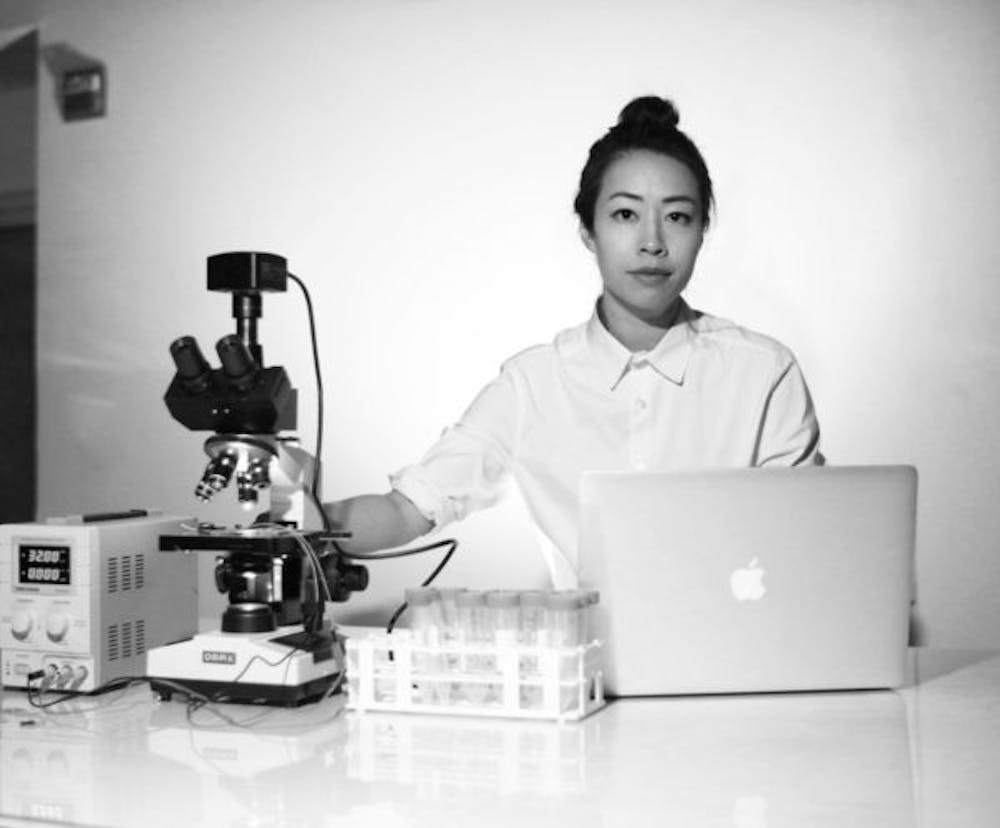

Ani Liu, an artist whose work imagines the future, could not have imagined this present.

Liu is a 2019–20 University Arts Fellows. She currently teaches Reality R&D: Designing Speculative Futures, a course cross-listed in Anthropology, Architecture, Visual Arts, and Science and Technology.

Part of the class involves doing what Liu calls “futuring” — designing and envisioning worlds which we hope for, worlds that shock us, and even worlds we fear. Liu and her students were interested in how technology affects intimacy months before COVID-19 upended traditional socialization, forcing everything from meetings to dates to classes onto the internet.

“Certain themes that were more speculative are now almost fast-forwarded,” Liu said.

In a way, Liu has always been in the business of fast-forwarding. Bridging the gap between science and art, she explores the relationship between technology’s development and our cultural, social, and emotional lives.

“I’m interested in this dichotomy: We think scientists are rational and artists are emotional, and that they are at odds,” Liu said. “But I find that a lot of innovation happens when both come together.”

Liu’s work is a direct result of that coming together. From a young age, her parents pushed her towards math and science. Yet, even then, she knew she wanted to be an artist. After graduating from Dartmouth College, she studied architecture at Harvard, where she noticed how much her classmates’ designs were constrained by the software they used.

“I started to look at how designed objects design us, how technology shapes us,” she said.

After receiving an M.S. from MIT’s Media Lab, Liu spent some time at the design firm IDEO, where she served as researcher in residence. There, she worked on conceiving a “food pharmacy” where patients could be prescribed diet and lifestyle changes in addition to drugs.

Although she loved the job, “for better or worse, I do have a strong idealism bone in my body,” Liu said. “I felt like my life is so short — I want to spend it pursuing the things I like the most.”

So Liu turned to full-time artmaking. Some of her earliest projects engaged with our sense of smell, distinct from our other senses in that it bypasses relay centers in the brain to hit at our deepest emotional memories. One such endeavor was engineering a plant that smelled like a loved one who had passed away. Liu developed that project into a set of perfumes that smelled like her husband at various emotional and physical stages: one after a workout, one after they had sex, and one after they had a fight.

Before COVID-19, Liu had set her sights on a project about pregnancy. She’d given birth to her daughter only months before and became fascinated by products marketed towards women — creams that made stretch marks disappear, lotions that made vaginas smell “better” — that implied the female postpartum body was something to be fixed.

“Things that are so inherently biologically female get recast in a negative light,” Liu said.

So Liu set out to challenge that notion. Entitled “The Simulator,” her project involved a series of speculative devices that gave users the experience of being pregnant: nausea-inducing pills, underwear designed for incontinence. Liu wanted to explore how the physical discomfort of bearing a child could be useful and what it could teach.

“During pregnancy, I became more patient, humble. I moved slower. I was very empathetic,” Liu said.

She researched the future of artificial wombs and animal surrogates, asking what could be missed in losing the physical experience of pregnancy. She also looked to the past.

“In going through pregnancy, I become interested in the history of medicine and how it looks at pregnant bodies,” Liu said.

Most writing she came across on the subject was inherently partial — the authors, typically men, had never been pregnant themselves. In her work, Liu has often held the role of not only an artist and researcher, but of a cultural interrogator of sorts. This mentality is clear in Liu’s most well-known piece, which began in response to then-presidential-candidate Donald Trump’s infamous “grab them by the pussy” comment. Liu wanted to create a piece that explored what this meant for women and the control they had — or didn’t have — over their bodies.

While working, Liu heard about a recent experiment at Stanford, in which scientists used electric currents to direct the motion of single-celled paramecia, controlling the creatures like avatars in a video game. The experiment demonstrated galvanotaxis, or the ability of microorganisms to move according to an electric field.

This was Liu’s first thought: “I wonder if this works with sperm.”

She went home and asked her husband for a sample. He agreed. She then wired a simple circuit and hooked the system up to an EEG headset that would translate her brain activity into electrical impulses to drive the sperm.

Liu trained herself to control the sperm with her brain waves and invited participants to do the same at exhibitions. The participants, in awe, told her that this experiment changed the way they thought about the gendered power dynamics of our society.

“Most people who first hear about it think ‘That’s just crazy,’” Liu said. “But I think that it really does speak to the absurdities that female bodies face. A lot of women who tried it said they spent so much of their lives taking contraceptives, that in some ways they felt powerless in this domain.”

For the women who experienced her project, Lui said, “being an active participant was very cathartic.”

Liu has also explored our microbiome, the diverse set of bacteria that lives in and on every one of us, and in a way, constitutes who we are. In “Biota Beats,” Liu worked with a team of biologists to create music from an individual’s unique patterns of gut flora. And in “Kisses from the Future,” a simple smooch on a petri dish gives rise to vivid colonies of bacteria, derived from our own patterns of touching and kissing others.

In her class at the University, Liu has emphasized both practical maker techniques — 3D printing, circuit building, laser cutting, and so on — and the theory of design. Students consider speculative projects and the ethics behind them, touching on topics from artificial intelligence to biohacking.

Liu has had to make dramatic changes to her class syllabus, now shifting heavily towards the digital. In the midst of a pandemic, remote tools have gained a new urgency. But so has artwork that enables people to connect — with each other, and with themselves. So too has work such as Liu’s, which engages with technology but is rooted in the experience of the self.

“One of the things I was always good at was connecting things other people wouldn’t have related,” Liu said. In high school, to memorize the elements of the periodic table, Liu associated each element with a certain flavor or smell — for instance, a lemony aroma for the noble gases. She created bodily associations for hard facts.

“I am a very visceral person. A lot of the things I learned I had to develop an emotion for or build in my body,” Liu said. This instinct is alive in her projects, which are rooted in science but come alive in the senses — smell, sight, taste, sound, and touch.

“I want someone to feel,” she said.