As the coronavirus pandemic swept across the globe and onto the University’s campus, many students were surprised to see unprecedented action taken to halt its spread. While this may be true, the nearly 300-year-old University has weathered multiple pandemics in the last century alone.

The pandemic most familiar to current undergraduates is likely the 2009 swine flu outbreak caused by a novel H1N1 virus. Like the term “coronavirus,” H1N1 refers to a class of viruses, some of which are common enough that significant portions of the human population are already immune to them. Few people, however, were immune to the new strain that emerged in Mexico in the spring of 2009 before quickly spreading to other countries.

The University was prompt in its respond to the outbreak, sending an email to the campus community one week after the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) publicly announced the first infections in the United States in April 2009. Though the initial email said that all operations could continue as normal, further spread caused University Health Services (UHS) to ask students with swine flu symptoms to self-isolate and call for a medical evaluation by phone rather than visit the clinic in person.

Though all on-campus gatherings were allowed to proceed as planned, the University temporarily stopped funding undergraduate travel to Mexico, the epicenter of the pandemic. Similarly, in the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic this February, student life continued as normal with the exception of travel-funding restrictions for countries, such as mainland China and South Korea, labeled with a CDC Level 3 Travel Health Notice.

Though the University’s response to COVID-19 initially followed the same trajectory as the 2009 pandemic, the current pandemic differs from H1N1 in several crucial ways, which explain the more drastic measures taken today.

First, while the novel viruses initially inspired similar levels of panic, COVID-19 is significantly more deadly than swine flu. The CDC estimates that 151,700–575,400 people died worldwide from the 2009 pandemic, marking a fatality rate of around 0.02 percent. By contrast, COVID-19 has a death rate of between 0.66 and 1.38 percent and has killed 67,000 people in just three months.

Second, unlike COVID-19, swine flu responds to traditional antiviral medications both as a preventive measure and to treat cases in high-risk individuals, though most cases are resolved without them. In 2009, UHS provided antiviral medications to patients with pre-existing medical conditions such as asthma, diabetes, and compromised immune systems, as well as for individuals whose condition significantly worsened without treatment.

At present, there are no antiviral medications known to be effective against COVID-19, leaving high-risk patients especially vulnerable to dangerous complications.

Third, the CDC approved and distributed an H1N1 vaccine within six months of the first infection within the United States. The University began administering the vaccine to high risk groups in late October of 2009 and made it available to the entire University community by January. Widespread vaccination helped minimize community spread, allowing the University to suspend cautionary measures and resume business as usual by February.

Experts estimate that a vaccine for COVID-19 will not be available for at least 18 months, making social distancing the only available method to prevent community spread. As a result, the University implemented much stricter social distancing measures than it did in 2009, including requiring most students to leave campus.

In terms of level of disruption to University operations, the closest comparison to COVID-19 may be the 1918 flu pandemic in 1918 and 1919. Caused by an H1N1 virus, the 1918 flu pandemic infected around a third of the world’s population, killing as many as 50 million people.

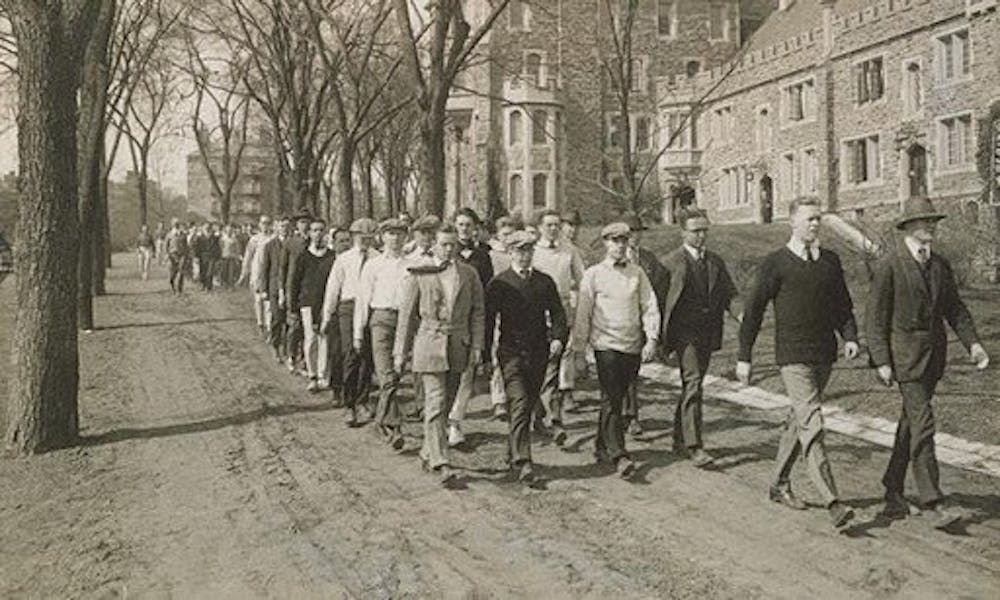

In an attempt to prevent the pandemic from reaching campus, the University instituted a policy of “protective sequestration,” designed to protect the healthy population from contact with the outside world. This policy involved a ban on students from leaving campus and the creation of a disinfecting plant outside campus. All visitors were checked for symptoms, received a throat spray, took hot baths, and had their clothes taken overnight to a disinfecting room.

These extreme measures were possible in large part because the University had been temporarily converted into a mobilization camp to train soldiers to fight in World War I, which ended in November 1918, just after the peak of the 1918 flu pandemic. Students who disobeyed could be court-martialed, and guards were posted at the entrance to all dormitories to prevent unauthorized visitors.

“The military presence on campus made it easier to enforce sequestration, the student body was much smaller, and the town was more isolated from the outside world,” notes the Princeton Alumni Weekly article in explaining why the University was mostly spared from the pandemic.

By contrast, today’s students are accustomed to moving freely around campus, the town, and even farther afield to nearby cities, and many people in town regularly commute to New York City or Philadelphia for work. The level of interaction between the University and the surrounding community and the difficulty of imposing such strict rules for civilian populations suggest that protective sequestration was never a viable response to COVID-19.

As with the novel coronavirus, there were no known pharmaceutical treatments for the 1918 flu, and a 1919 article in The Daily Princetonian described the University’s medical facilities as “pitifully inadequate” for the volume of patients at the peak of the pandemic.

Communities around the world face similar challenges today, with coronavirus patients dying as hospitals struggle to access ventilators and lifesaving personal protective equipment.

Now, the University, along with many other states and countries, has turned to “social distancing” to reduce the burden on healthcare systems. Social distancing protocol requires that people who do not live together maintain a distance of at least six feet between them at all times. Because most University students live in dormitories where social distancing is nearly impossible, the majority of students were required to leave campus by March 19.

Though the University could not implement protective sequestration as it did a century ago, it seems to have avoided overwhelming local medical infrastructure thus far.

Another difference between the University’s response to 1918 flu pandemic and the novel coronavirus? In 1918, the ‘Prince’ stopped publishing for six months as its writers fought the war in Europe and the flu at home. Today, we continue to share the news each day from our homes on campus and across the world.