At Princeton, few honors are more highly sought-after than the Shapiro Prize for Academic Excellence. Endowed by president Harold Shapiro GS ’64 in 2001, the awards are presented to 3 percent of underclass students for “outstanding academic achievement” in “intellectual pursuits that constitute the core of undergraduate education.”

Honorees receive a book and a banquet. But the benefits don’t stop there. A brief tour of LinkedIn shows that they also list the award on their résumés to tech companies, investment banks, and professional schools. Many recipients of the Pyne Prize are winners of one, if not two, Shapiro Prizes, as are many of the Princeton students who receive the Rhodes Scholarship.

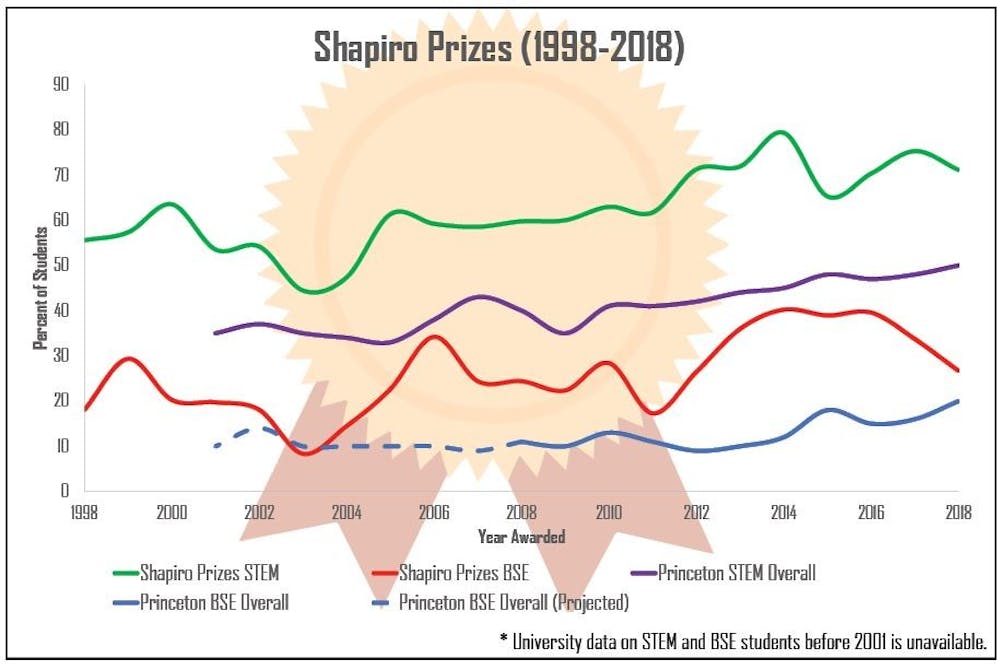

While Princetonians in any discipline can receive a Shapiro Prize, what they study appears to be as important as how much they study. Undergraduates concentrating in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) were consistently twice as likely to win during the past twenty years than their peers in the humanities and social sciences.

I compiled a record of the more than 1,700 Shapiro Prize recipients since the award was created in 1998. To collect this data, I retrieved commencement programs online and through the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library. Through the alumni directory, I tracked what departments recipients majored in.

I discovered huge disparities in the number of prizes that individual departments have accumulated. Some departments — which weren’t necessarily the largest — sported a dozen winners every year, while others hardly had one per decade. The results raise questions about whether the Shapiro Prize’s selection process — which is intended to identify academic talent — instead picks up on confounding factors.

Nearly two-thirds of all Shapiro Prizes have gone to STEM concentrators. Engineering students alone won more than a quarter of the awards. In 2014, engineering reached an apex, when eight-tenths of recipients studied STEM, whereas University-wide they accounted for just four-tenths of undergraduates.

Jennifer Rexford, Chair of the Department of Computer Science, said the trend was “easily explainable.” STEM departments, she explained, use the “dynamic range” of grades more often than in the humanities. An answer is right or wrong with little subjectivity. Someone who scores highly on a STEM exam will likely get an A or A+.

Rexford, a former member of the University’s grading committee, pointed out that STEM courses tend to repetitively test the same abilities. “If you take 10 math courses and got an A+ in one, the chance that you’re going to get an A or an A+ in the other nine is pretty high,” she said.

In contrast, it’s unlikely that a student who takes courses in, say, poetry, philosophy, and history will receive the same or similarly high grades across all of the different skills assessed in those courses.

The selection process for the Shapiro Prize involves residential college deans and administrators from the Office of the Dean of the College reviewing the transcripts of the top 10 percent of a class, defined by their grade point averages (GPAs).

“For Shapiros, we use the official university 4.0 GPA list as our starting point,” Senior Associate Dean of the College Claire Fowler told me in a fall 2018 interview.

A’s and A+’s receive equal weight, and A+ statements aren’t factored into consideration. Students who received a single A- in 12 classes — among an otherwise perfect record — are evaluated differently than those who had a 4.0 in eight classes but elected to P/D/F one of them. Fowler said that the committee doesn’t “restrict decisions to GPA alone.” It takes courses’ breadth, depth, and rigor into account.

“When you get to the top of the class, it gets pretty competitive,” she said. Although she told The Daily Princetonian in 2016 that the selection committee is “mindful” of grading differences between departments, records show that STEM concentrators have won the majority of Shapiro Prizes every year since they were established, despite comprising half or less than half of the student body.

Graphic Credit: Harsimran Makkad / The Daily Princetonian

Math, Computer Science, Economics, Molecular Biology, the Wilson School, and Physics had more Shapiro Prize winners — and fewer students — than the other 31 departments combined.

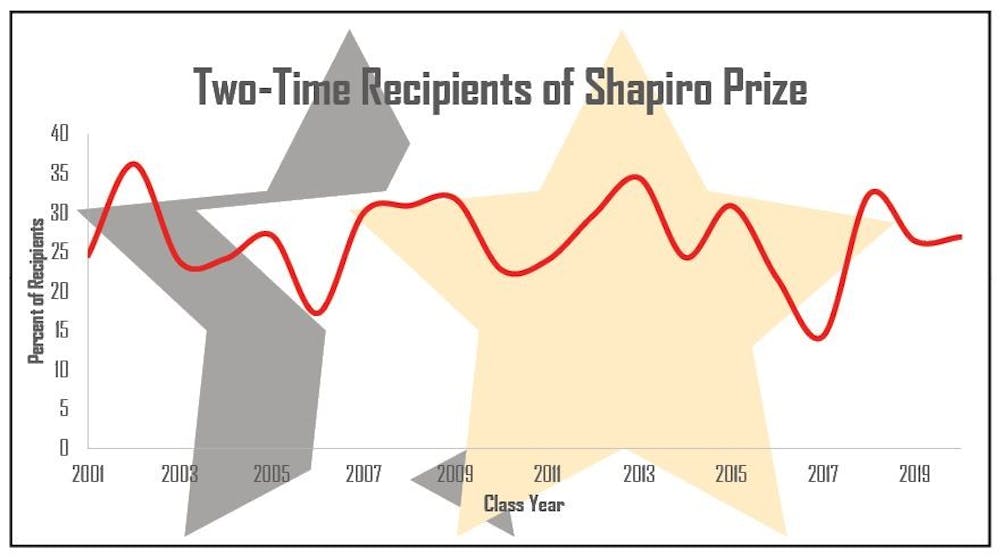

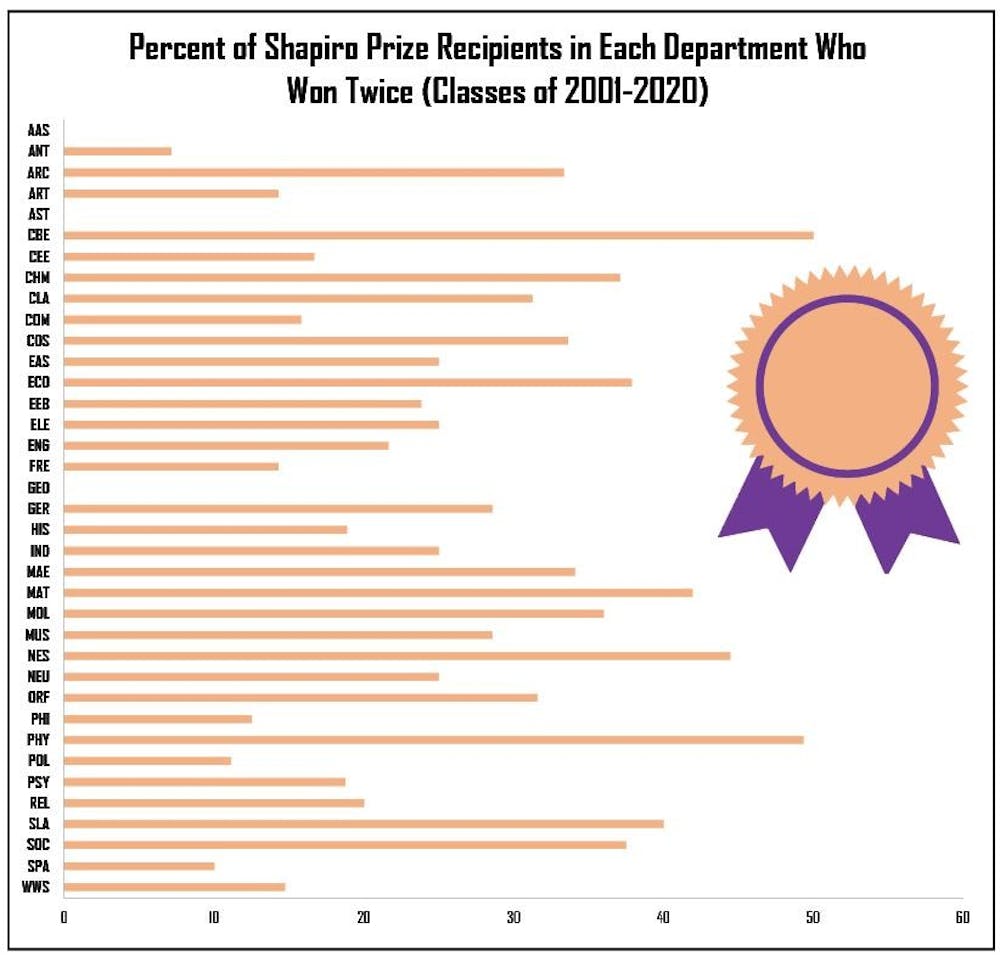

Twenty-eight percent of Shapiro Prize recipients were two-time winners. That number peaked at a full third in 2002. Half of Chemical and Biological Engineering recipients were “two-timers,” while Anthropology had virtually none.

Graphic Credit: Harsimran Makkad / The Daily Princetonian

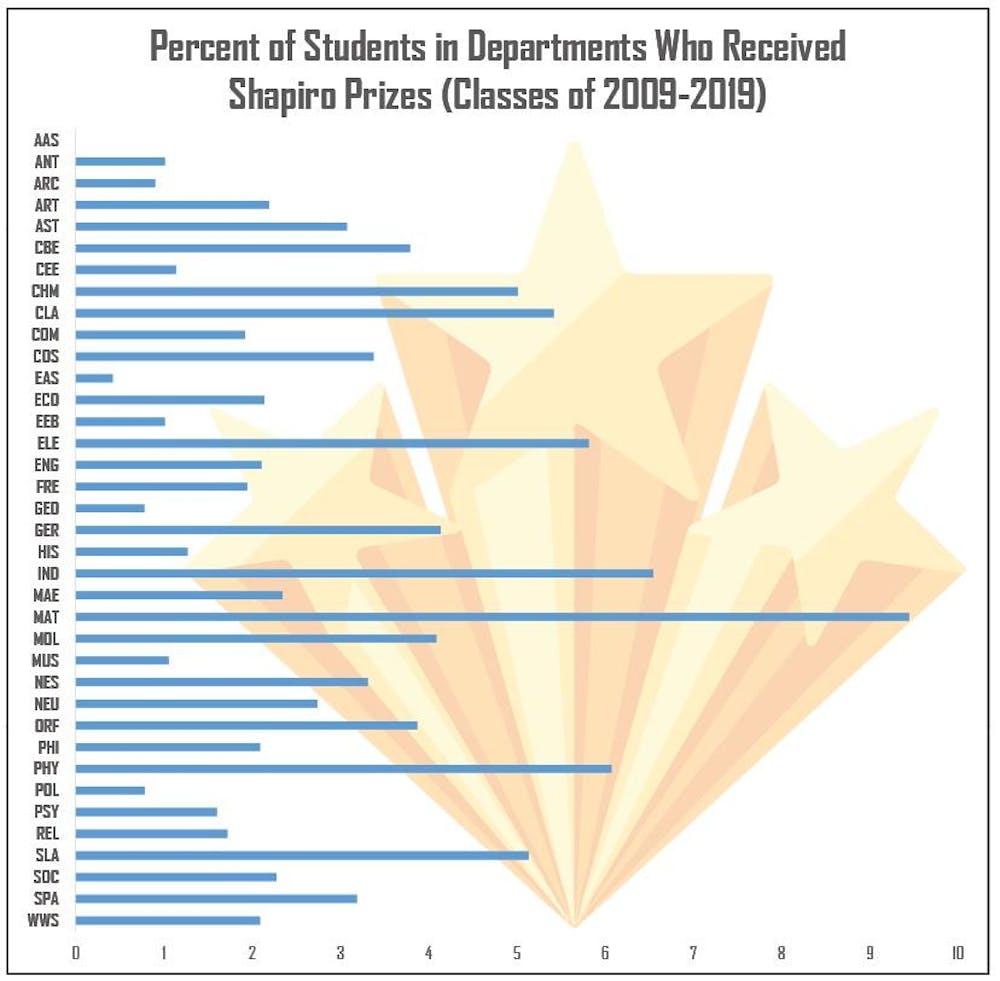

I used publicly available University graduation statistics to track how often students from various departments won in the Classes of 2009–2019. About 10 percent of math majors received a Shapiro Prize, followed by 7 percent of independent majors and 6 percent of physics majors.

While the sciences took the highest rankings, several small humanities departments — such as Classics, German, and Slavic Languages & Literatures — were sprinkled at the top of the list. In contrast, less than 1 percent of Architecture, Politics, Geosciences, East Asian Studies, and African American Studies concentrators each won Shapiro Prizes.

Natural science concentrators were 10 percentage points overrepresented relative to the fraction of all students for which they accounted. The social sciences were 15 percentage points underrepresented.

Fowler declined to comment on my analysis, and multiple residential college deans refused to be interviewed.

Harsimran Makkad

Math professor János Kollár thought that the Shapiro Prize’s emphasis on breadth and depth gave an edge to STEM students. “I’ve never seen a humanities major in a 300-level math class,” he said. “I’m not saying there are none, but it is much more frequent that some science major has a very strong interest in the humanities.”

Former president Harold Shapiro confirmed that he doesn’t participate in the selection process. He did note, however, that professors have “a very good notion of which courses are hard to do well in and which aren’t,” and concurred with Kollár’s opinion.

“Humanities and social science professors will say to me their best student is an engineer this year, or their best student is a physics major. You very very seldom hear the reverse,” he said.

These Shapiro Prize statistics imply three possibilities: STEM departments get a greater share of the strongest students, STEM students are more rounded in their studies, or departments’ differential grading trends are swinging outcomes.

The first and second options could be true. But the selection committee would spark an outcry from humanities departments if it openly admitted as much. The third is absolutely true — to a certain extent — as my previous review of the University grading data reveals.

STEM departments have wider grading distributions that reliably reward high-scoring students, as shown by the fact that they give A+’s twice as frequently as their counterparts in the humanities. For these reasons — along with others — grades are deeply flawed metrics of aptitude. The Shapiro Prize should be reformed to better reflect students’ achievements.

An alternative selection process can be created by pulling a page from the rule book of Harvard University’s Hoopes Prize. At Harvard, professors nominate students who completed “extraordinary undergraduate work.” This award is usually for theses and junior papers, but anything is fair game. Nominators also receive recognition for their “excellence in the art of teaching.” Winning projects are then stored in the Lamont Library for two years.

While this process isn’t perfect, it is at least informed by the judgment of erudite instructors, rather than fickle letters.

This is the first column in a series examining the outcomes of academic awards. Stay tuned for insights on Phi Beta Kappa later this week.

Liam O’Connor is a senior geosciences major from Wyoming, Del. He can be reached at lpo@princeton.edu.