Twenty-four hours before this year’s South Carolina democratic primary, Justin Wittekind ’22 was driving through Massachusetts, screaming, en route to see his “king.”

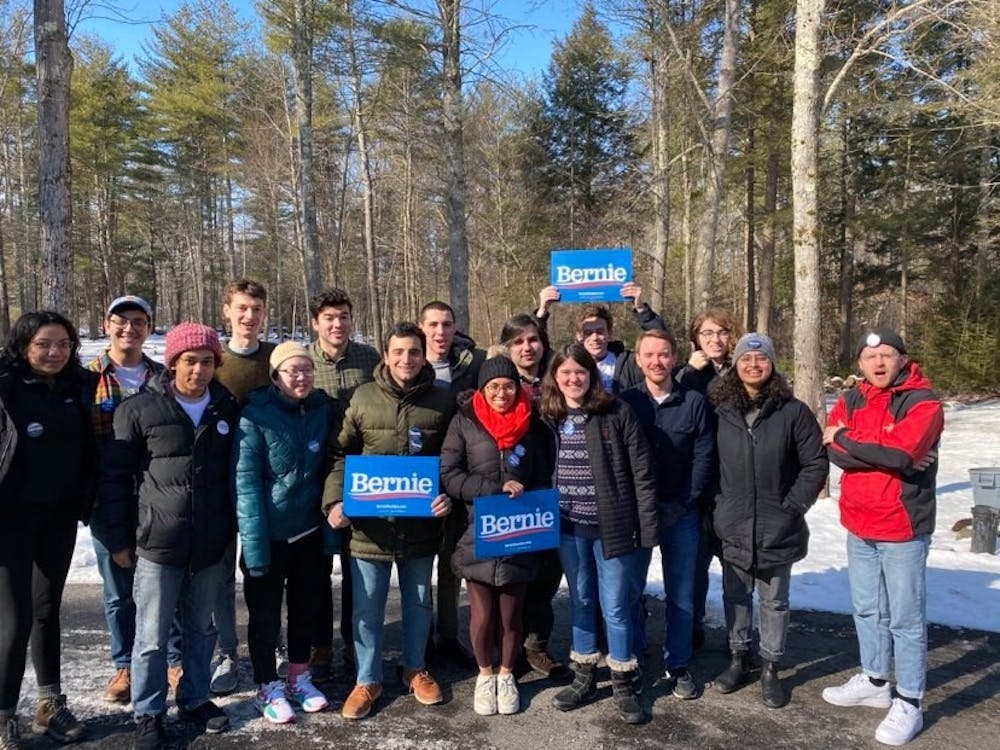

This campus is oft bemoaned as apathetic and apolitical, and this country’s college-aged generation as lazy and unaware. But “Princeton for Bernie,” an outgrowth of Princeton’s Young Democratic Socialists chapter dedicated to Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign, defies those labels. The group includes around 50 undergraduate students, plus a slew of graduate students who, said Wittekind, “are the ones really bringing the fire.” Around 25 people show up for weekly phone banks; he and fellow member Jason Seavey ’21 alone have made over 600 calls, by Wittekind’s tally.

While he speaks for the group, Wittekind is quick to clarify he is by no means its leader. To members of Princeton for Bernie, the organization’s horizontal structure and lack of formal leadership is a point of pride.

“It’s ‘not me, us.’ That’s the Bernie mantra,” said Wittekind. “It’s not me — Justin. It’s us — the car.”

But the “us” of Bernie lovers extends well beyond that Boston-bound car. A recent poll by The Daily Princetonian found that a plurality of Princeton students support Senator Sanders in the Democratic primary. And the group seems hell-bent on expanding its reach past the Orange Bubble.

“The thing that’s so exhilarating about the Bernie campaign,” yelled Wittekind over the excited shouts of other Princeton students in the vehicle, “is just the huge numbers of young people who are involved.” He explained the group has been in touch with Rutgers organizers, field organizers for the campaign itself, and students across the country through social media.

On the Princeton for Bernie agenda this spring: more van trips to key primary states, more phone banks, and in an ideal world, a long-due celebration when — in Wittekind’s words — “our king is finally crowned.”

Another point of pride for the group: it’s the fastest-growing campaign infrastructure on campus. “Everyone else seems to be dissolving,” Wittekind said.

He has a point.

Late last Sunday, roommates Nate Moore ’22 and Bobby Doar ’22 were sitting on their common room couch. Doar was mid-problem set, Moore midway through an email to Celia Buchband ’22, president of Princeton College Democrats, about room space for a pre-Super Tuesday pro-Pete Buttigieg phone bank. A CNN alert flashed across Doar’s computer screen. He turned to his right.

“Pete dropped out.”

The email on Moore’s desktop went unsent.

A self-described political junkie from Wilson, Wyo., Moore first heard about Pete Buttigieg during the then-35-year-old’s bid for DNC Chair. The campaign ended in failure, but the name stuck; by the time the Washington Post published a profile of the South Bend, Ind. Mayor in Jan. 2019, Moore was smitten. He donated to Buttigieg the day after he announced his candidacy, joined every email list he could, and put his name down as a potential volunteer.

In early December, out of the blue and into Moore’s inbox came an email from the Buttigieg campaign. They had a volunteer opportunity. Was there a time he could talk?

By the following week, Princeton had a “Students for Pete” chapter, and Moore was its president. The campaign provided him with toolkits, info sheets, and agendas; he had access to weekly phone calls with campaign officials like Marv McMoore, Buttigieg’s National Youth Engagement Director, and Chasten Buttigieg, the mayor’s husband. Twenty-odd students registered interest in his group. A core dozen regularly showed up, motivated largely by the same reasons as Moore.

Buttigieg “was such a contrast to everybody else running,” said Moore. “They were all septuagenarians, as old as my grandparents. He obviously isn’t. He has an incredible way of expressing complex — and progressive — policy ideas in a way everyone can understand, and in a way that moderates can really rally behind.”

Buttigieg’s message was well-established. His visibility? Not so much. So the members of Princeton for Pete got to work — which for them, really only meant one thing.

“In New Jersey,” said Moore, “because the primary is so late, there’s not much you can do besides phone bank.”

Phone bank they did, until that Sunday CNN alert. Now the twenty-odd students have a choice to make: where do they go now? Moore, for one, knows.

“Joe Biden,” he said. “What matters to me the most is beating Donald Trump, far more than policy issues. I don’t agree with Joe Biden on everything, and I think there are some issues with him as a candidate. But I think he’s the best chance to beat Trump.”

His compatriots may choose to follow him to the Biden camp, but if they’re looking for the same kind of organized political activism they found for Buttigieg, they’re out of luck. Buchband said she is aware of only three student groups supporting presidential primary campaigns: Sanders’, Buttigieg’s, and Senator Elizabeth Warren’s.

Buchband is an associate chief copy editor for the ‘Prince.’

In October, the ‘Prince’ profiled three students: Harshini Abbaraju ’22 and Eric Periman ’22, the founders and co-presidents of Princeton for Warren, and Josiah Gouker ’22, the founder of Tigers for Julián. Four months later, all three have joined Team Bernie.

Although around 70 students joined the Princeton for Warren listserv in the fall, Dylan Shapiro ’23, a student still organizing with Princeton for Warren, admitted, “They’ve never all been in one place at the same time.”

“We kind of fell dormant,” he said. “Princeton is a difficult campus to organize at, but we’re hoping to pick back up — to help get Elizabeth across the finish line.”

To that end, Princeton for Warren held and widely advertised a phone bank this Monday, on the eve of Super Tuesday. Three people showed up.

Shapiro said he grounds his support for Warren in the simple reality that “no president is ever going to be someone I agree with on every issue.”

“But Elizabeth is the one most interested in actually listening to and being held accountable by the communities most affected by her policies,” he explained.

Abbaraju and Periman feel differently.

In October, Periman cited Warren’s support for “Medicare for All” as exemplary of how her campaign empowers working and middle class people. Now, “Medicare for All” is the reason he supports Sanders.

“It’s non-negotiable for me,” he said. “I feel like my values didn’t change, but Elizabeth Warren’s did — or at least her stances changed.”

An Iowa native now living in South Carolina, Abbaraju spent most of last summer campaigning for Elizabeth Warren in not one, but two early primary states. But ultimately, she realized Warren did not align with her politically.

“It took me a long time to come back home,” she said of her eventual public support for Sanders. “If we want to beat Trump, we can’t just be against him. We have to present the boldest possible contrast to him, and that’s Bernie.”

Abbaraju said that although she had privately switched to Sanders’ camp for some time, she felt compelled to share her support for him on social media in the wake of sexism allegations toward him from members of the Warren campaign.

“I was really, really disappointed in Senator Warren after that,” she said, adding that as a feminist who is particularly cognizant of race and class issues’ intersection with gender issues, “Senator Sanders is someone I’m proud to support.”

Periman said he feels strongly about deconstructing what he believes is the myth of the uniquely menacing “Bernie Bro.”

“He wins every demographic under age 55,” he said. “So it’s saddening — and honestly, a little hilarious — to see people go after him for his base of ‘Bernie Bros.’”

Gouker’s past candidate of choice, Julián Castro, may be campaigning for Warren, but Gouker himself has made his choice clear.

“I think [Sanders] represents the best chance we have right now to bring about necessary progressive change in the executive branch,” he wrote to the ‘Prince’.

Wittekind is right: with every day and every candidate to drop out of the race, his organization grows. But what drew him to the campaign in the first place? Although he supported Sanders in his initial 2016 run, he couldn’t fully articulate why until earlier this year — “I was a fetus,“ he said, “I had incoherent politics.” Now, his message to potential voters when knocking doors for Sanders is simple: You have a right to be angry. So let’s do something about it.

His message for other Princeton students?

“If anyone out there is feeling a slight Bern-ing sensation, come find me.”