If you had asked someone in the winter of 2018 what the Democratic field of candidates would look like now, I doubt many would be able to predict the reality we are watching today. Even if you asked someone last summer, they likely would not have been able to guess.

Part of that has to do with the surprising rise of Pete Buttigieg, who’s jumped from mayor of South Bend, Ind. to a possible frontrunner. The surprising early drops of Senators Kamala Harris and Cory Booker would also have thrown off pundits a year ago. Ultimately, what started as the most diverse field in history is now dominated by white candidates.

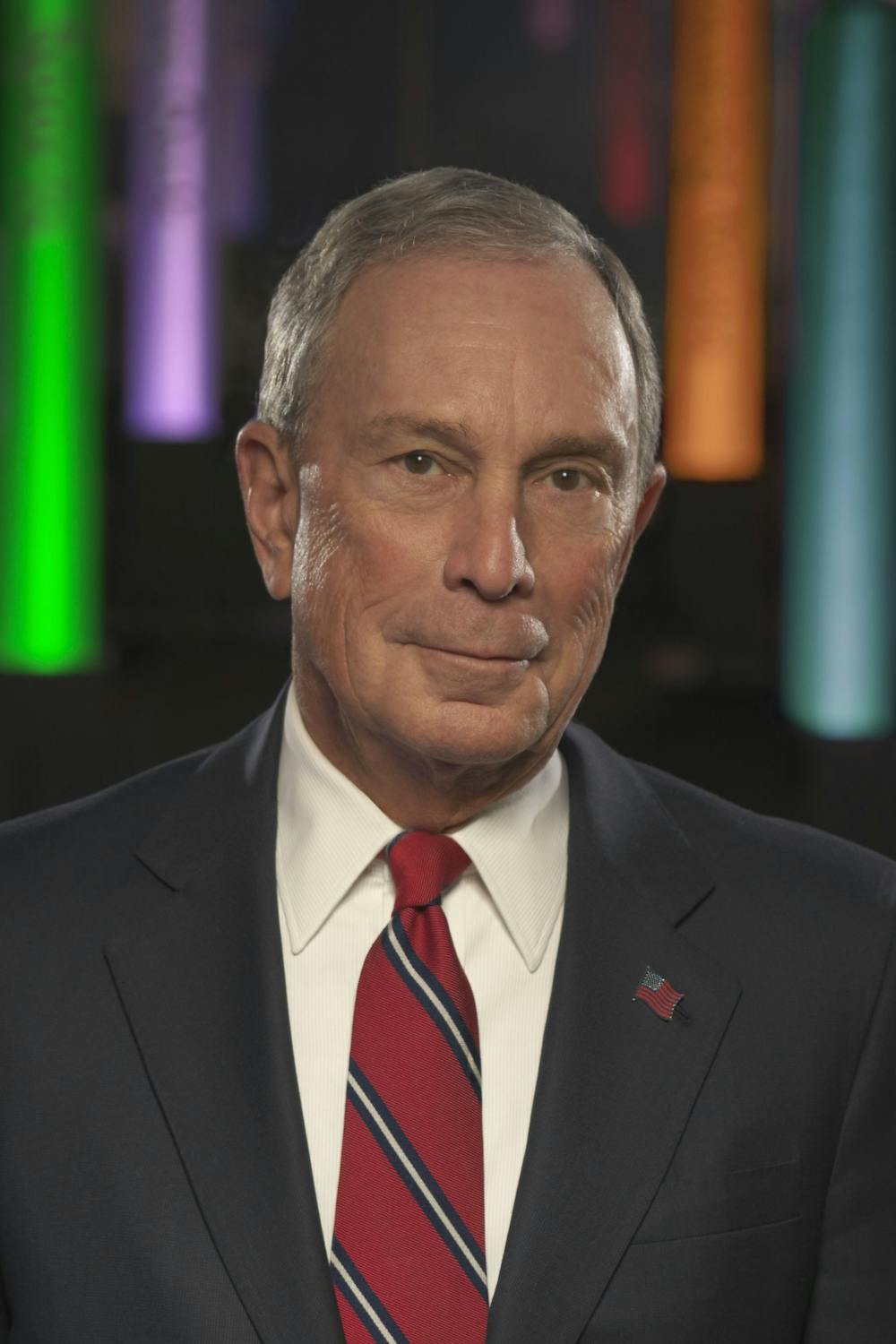

At the end of November, yet another surprise wrinkled the race for the nomination when Michael Bloomberg, the former mayor of New York City, declared his candidacy. Bloomberg’s subsequent rise, and the money that drives it, reveals the structural barriers that still shape our politics and the imbalances in the primary process.

Bloomberg announced his candidacy nearly a year after the first candidates entered the race. With a $60 billion fortune behind him, Bloomberg has pumped hundreds of millions of dollars into advertising, incentives for his staff, and earned media coverage — all of this has combined to make him a looming threat to the leaders of the field as the primary season ramps up, while also allowing him to evade many of the mechanisms of accountability that other candidates must face.

It is not just his spending over the past few months that has contributed to his ascent — over the past twenty years, Bloomberg has used his fortune to build a web of connections and influence nationwide. That network includes Princeton: Bloomberg Hall, which opened in 2004, is named for his daughter, Emma Bloomberg ’01.

A recent New York Times investigation revealed the vast extent of his reach. In just 2018, Bloomberg spent $2.3 billion across 103 cities on philanthropic and political causes; in 2019, he spent $3.3 billion. The investigation also revealed multiple instances — involving the Center for American Progress, EMILY’s List, and Everytown for Gun Safety — in which organizations that rely on Bloomberg for funding felt pressured to moderate their stances or temper their criticism of him.

The politicians whose campaigns he has contributed to, combined with the people he can tap to work for his campaign, give Bloomberg a base of support unparalleled by his competitors, who simply can’t access the same resources he can.

As his stature has risen, so have a host of concerning aspects of his record. Most alarming to me is his record on race in his time as mayor, particularly his policy of stop-and-frisk.

For years, Bloomberg has defended stop-and-frisk, a policy which disproportionately targeted young Black and Latino men – these demographic groups consistently comprised 80 percent of those stopped by police. Around 90 percent of those stopped were innocent.

Finally, in November (just before he announced his candidacy), Bloomberg apologized for the policy. But in a recently unsurfaced video from 2015, Bloomberg said, “95 percent of your murders — murderers and murder victims — fit one M.O. You can just take the description, Xerox it and pass it out to all the cops. They are male, minorities, 16 to 25. That’s true in New York, that’s true in virtually every city… We put all the cops in minority neighborhoods. Yes. That’s true. Why do we do it? Because that’s where all the crime is … the way you get the guns out of the kids’ hands is to throw them up against the walls and frisk them.”

Bloomberg also defended stop-and-frisk in 2018, denying that it violated civil rights.

By 2015, a federal judge had already called stop-and-frisk an instance of racial profiling and an unconstitutional violation of civil rights. Apologizing for the video, Bloomberg glossed over his role in expanding the policy, blaming it instead on his predecessor, Rudy Giuliani. At its peak in 2011, nine years into Bloomberg’s time as mayor, over 685,000 people were stopped.

These past statements reveal a disregard for the very real effects of stop-and-frisk on communities of color. Bloomberg’s 2015 remarks reinforce the stereotyping of young men of color as uniformly criminal, literally saying they are identical copies of one another. He used this supposed criminality to justify harsh and violent tactics against millions of people, very few of whom actually fit that characterization.

And even after losing in the courts and losing the political battle, years down the line, Bloomberg is still unable to fully acknowledge his complicity in a law enforcement regime that abused the rights of people of color on a large scale, with effects that continue to ripple across communities nationwide. And he doesn’t have to — without the reliance on campaign donations or the need to compete in the first few states, he can’t feel the impact of decreased public support caused by these, or any other, statements.

This is the problem with a billionaire who enjoys deep connections around the country, self-funding his campaign for the Democratic nomination. It is difficult to hold someone accountable who is not beholden to anyone for funding. It is challenging to campaign against someone who can drown you out with an unending stream of advertising and the media coverage that accompanies it.

Already Bloomberg is circumventing the rules other candidates must follow. He skipped the early primary states and the narrowing of the field that comes with them, focusing his attention on the high-delegate states that vote in March. While candidates such as Andrew Yang had to drop out without the support or resources to push on, Bloomberg still has a chance to compete.

After the DNC rejected Julián Castro and Cory Booker’s requests to alter the debate qualification rules to allow for a more diverse lineup, the DNC hypocritically lowered its standards, by removing the donor threshold, to allow candidates such as Bloomberg to compete.

Bloomberg’s surge should concern those of us who hope for an open competition for our votes, or for a primary season in which candidates have to respond to our desires rather than the other way around. A better system would allow anyone to compete regardless of personal wealth, where candidates would compete on the merits of their messages, rather than the depth of their pockets.

Maybe the country does decide that Bloomberg is the answer to Trump, maybe people do forgive him for his previous policies and statements — but that choice should be made on an even playing field. Bloomberg should have to fight with everyone for our vote, and we should want him to have to.

Julia Chaffers is a sophomore from Wellesley, Mass. She can be reached at chaffers@princeton.edu.