Few things worry first-years more than the fear of not making friends in college — and for good reason. Harvard researchers found in 2017 that nearly half of first years felt that their peers had larger friend groups than themselves. A 2018 national survey of 88,000 students across 140 institutions confirmed that two thirds “felt very lonely” within the past 12 months.

Princeton’s demographics complicate — if not worsen — this anxiety. With 13 high schools sending enough people here to fill McCosh 50, it may be hard for first-years who can’t rely on prior friendships to fit into Old Nassau’s clubby social life. Orientation week is crammed full of activities to stir the pot. After those first few weeks, however, a once-united incoming class fractures into isolation.

A project titled “How to Be Important at Princeton” by Heide Baron ’20, Annie Xie ’20, and Julia Yu ’19 sheds new light on this process. I chipped in by giving them the eating clubs’ membership rosters. They did the rest. Here’s how it worked: they tracked majors, teammates, roommates, hometowns, dining choices, and residential colleges. Each group was assigned a varying amount of weight based on its size.

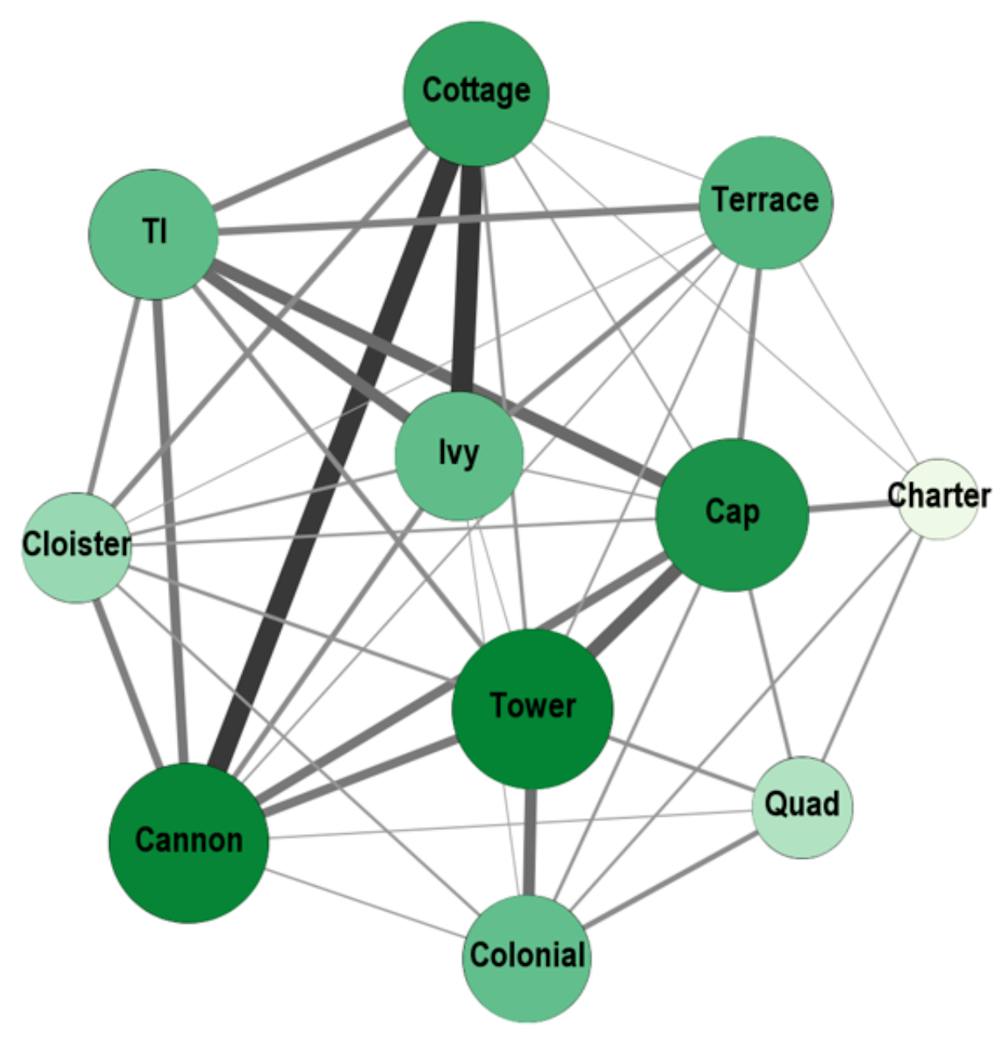

Then, they mapped relationships between groups — such as majors and roommates. Their research reveals many of the networks that define Princetonians’ sophomore and junior years and highlights the need for more freewheeling social mixers beyond Orientation.

“In the whole student population, there’s definitely communities that have connections in themselves and are very tight,” Xie told me. She admitted that the study had missing links — hobby-based club members, class attendance, and zee groups, to name a few. Non-athletes often form networks within these assigned groups, so athletics receive a disproportionate amount of attention. But their intuitive results were still striking for the groups that were studied. They likely wouldn’t be too different for those that weren’t included.

Graphic Courtesy of Heide Baron ’20, Annie Xie ’20, and Julia Yu ’19

AB computer science concentrators from heavily represented New Jersey towns who were members of eating clubs, co-ops, and varsity athletic teams were the most socially connected students, according to their “Betweenness Centrality” algorithm. This finding is to be expected, considering that my own analysis of the Residential College Facebook found that New Jersey was the most common home state — with the municipality of Princeton alone sending 130 students. On the other hand, international students from poorly represented countries who weren’t affiliated with any major groups were the most socially isolated.

Bicker eating club members generally showed higher levels of interconnectedness on “the Street” than their sign-in classmates, though they also had a greater number of members to form networks. Students in Cottage frequently roomed with friends in Ivy and Cannon. The T.I.-Ivy-Cap chain was the second strongest.

Football fed into Cannon and Cottage. The latter took men’s ice hockey and men’s soccer as well. Men and women lightweight rowers went to Cloister, but the heavyweight men’s team chose Ivy.

Men’s lacrosse players were tied to the men’s football team, while the women’s track and swimming teams were closely associated. Social science departments — specifically politics, history, and economics — were the most prevalent majors among varsity athletes.

Students in economics, history, computer science, and operations research and financial engineering formed a tight cluster. Small science and humanities departments stayed on the fringe.

Social sorting isn’t necessarily negative in itself, because it’s a sign that people are forming long-term friendships. But there’s a growing demand for the kind of first-year opportunities to freely meet fellow students outside of the current — sometimes stuffy — networks. Plenty of posts from Tiger Confessions++, real talk Princeton, TigerCuff, and the now-defunct app Friendsy provide proof of that.

Graphic Courtesy of Heide Baron ’20, Annie Xie ’20, and Julia Yu ’19

Residential colleges could take a cue from Oxford by holding “formal halls” several times each semester. Students dress formally to attend these regularly scheduled, candle-lit dinners, in which they converse with classmates over food that’s a cut above the daily dining hall grub. They’re wildly popular, selling out within the minute that tickets become available. The Graduate College already hosts a variation of this tradition, called “high table.”

Student leaders have a key role to play as well. Class governments could spend their money on dinners that send randomly matched groups to meals at restaurants on Nassau Street instead of offering mass grab-and-go study breaks. Similarly, USG should once again pick up its project to pair seniors with first-years for college advice — but this time open it up to Tigers of all classes.

The first and last years of Princeton are dynamic. Students rush to introduce themselves to their new peers and then rush to meet more of them before waving goodbye. But the middle years are stagnant. While eating clubs do bring sophomores into new communities, they tend to solidify pre-existing social structures, and 41 percent of upperclass-students don’t belong to them anyways.

One of the best aspects of Princeton is its people. Few places have so many amazing musical prodigies, seasoned athletes, and bona fide geniuses all living together in the same place. Let’s meet up outside of frosh week and Reunions.

(Read the group’s full report or see their shorter PowerPoint presentation on my Google Drive.)

Liam O’Connor is a senior geosciences concentrator from Wyoming, Del. He can be reached at lpo@princeton.edu.