With a groundswell of activism igniting climate change protests all over the world, it seemed inevitable that the Fossil Fuel Divestment campaign in Princeton would roar back to life — and it has, propelled by the release of the IPCC’s 2018 report, which asserts that we must reach global carbon neutrality by mid-century, and the rise Greta Thunberg.

Demands for Princeton to divest from the fossil fuel industry began in Spring 2014 under the leadership of the Princeton Sustainable Investment Initiative, which operated until 2016. Spurred by the increased urgency for climate change action, the movement resurfaced this fall with a name that leaves no room for confusion: Divest Princeton.

The global divestment movement is based on two premises. Firstly, the movement affirms that climate change is caused by anthropogenic burning of fossil fuels; in order to mitigate the impacts of climate change in the near and far future, greenhouse gas emissions must be drastically curbed (i.e. the vast majority of fossil fuel reserves must be kept in the ground, unburned).

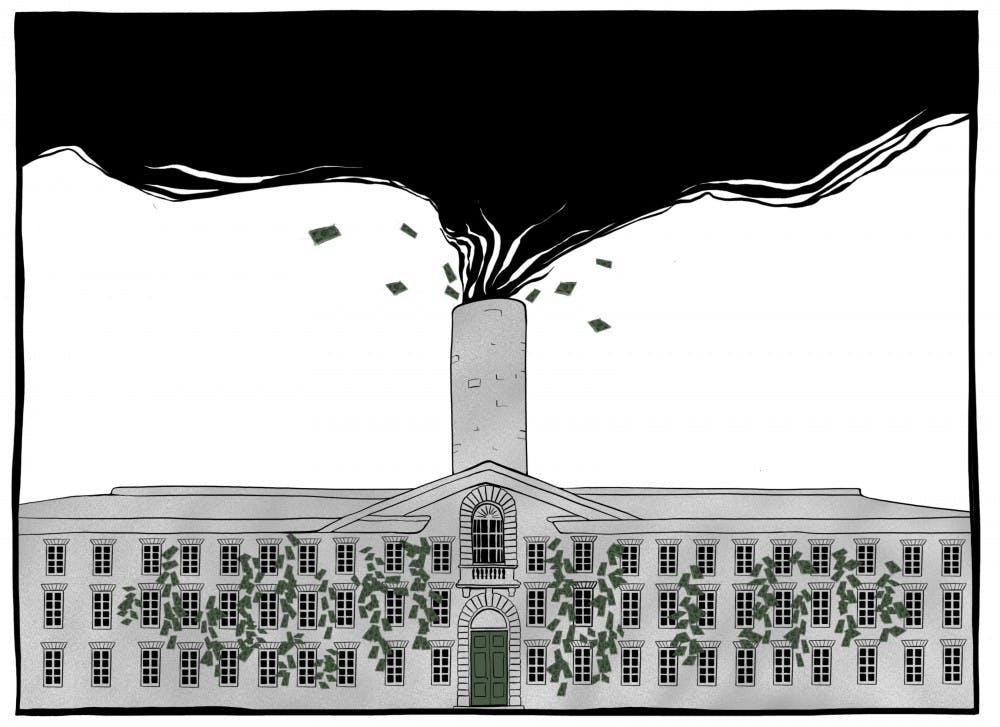

Secondly, the movement contends that by giving money to an entity (in this case, the fossil fuel industry), one provides both the monetary resources necessary for that entity to continue its activities and an ethical endorsement of what those activities entail. To fund an industry and profit from it is to be supportive of and complicit in its actions.

Given these facts, and given what we now know about the causes, effects, and necessary actions to mitigate climate change, it is logical, just, and necessary to stop investing in the fossil fuel industry. The proper question facing institutions is not whether to divest, but how to divest — how to get it right ethically and practically.

But with $5 trillion currently invested globally in oil, gas, and coal companies, what impact can a single university — even one as wealthy as Princeton — actually have? If the divestment movement’s immediate goal was to financially run the fossil fuel industry out of business, the movement would certainly come up short.

Divest Princeton and the divestment movement at large, however, aim to do something simpler: deprive the fossil fuel industry of its social license and legitimacy. The longer elite, well-regarded institutions like Princeton continue to defend fossil fuel companies by investing in them, the longer such companies can continue their actions, leading the world on a downhill trajectory towards a climate catastrophe.

Divestment is often dismissed as an overly confrontational and radical political movement. With politics often comes polarization and the fear of “losing” potential allies to the “divisive,” “partisan” nature of divestment — allies who might ordinarily support climate action.

It is true that the climate movement needs as many people as possible in order to make meaningful change. But in this case, where the science and the logical reasoning behind divestment are so definitive, it seems dubious to argue that such people are truly lost to the politics of divestment and to vested interests in maintaining the status quo.

It is even more questionable given the fact that, in today’s climate, supporting continued fossil fuel extraction is extremely political. Divestment is the necessary condemnation of the most damaging and polluting companies in the world; it is a necessary collective action that goes far beyond personal politics.

In order for Princeton’s divestment to have true integrity, the decision must come with full transparency about the reinvestment of the divested assets and full disclosure of a comprehensive timeline for its achievement. Reinvestment ought to prioritize companies whose products, services, and conduct align with global climate change mitigation goals, as well as the general improvement of society.

Little would be gained by divesting from some types of fossil fuels only to re-invest in other types of fossil fuels, and just as little would be gained by divesting from fossil fuels only to re-invest that money in entities responsible for other social inequities and harms.

Some have argued that it is hypocritical for Princeton to divest from fossil fuels when, currently and for the near future, the University will continue to be powered, at least partially, by fossil fuels. But Princeton has proudly committed to carbon neutrality by 2046 and has set clear steps by which that progress will be made.

A similar approach could be taken with divestment, where reinvesting the assets that are currently invested in fossil fuels would tie into the University’s overarching path towards decarbonization. This step should happen long before 2046, especially considering that a significant portion of the fossil fuel industry’s activity consists of searching for new fossil reserves. Thus, money invested in the industry today is, in fact, funding its existence in the future, as there is a time lag between the investment and its full carbon impact.

While Princeton’s research and teaching in the areas of climate change, decarbonization, and sustainability are commendable, the fact remains that Princeton’s investments do not align with the values and imperatives that arise from the knowledge it produces and disseminates.

Beyond being a basic moral necessity, it would be a moral victory for Princeton to lead its Ivy League peers — and to join institutions of higher education the world over — in withdrawing investments from the fossil fuel industry and using those funds to do right by the world of today and tomorrow.

Tali Shemma is a sophomore from Herzliya, Israel. She can be reached at tshemma@princeton.edu.