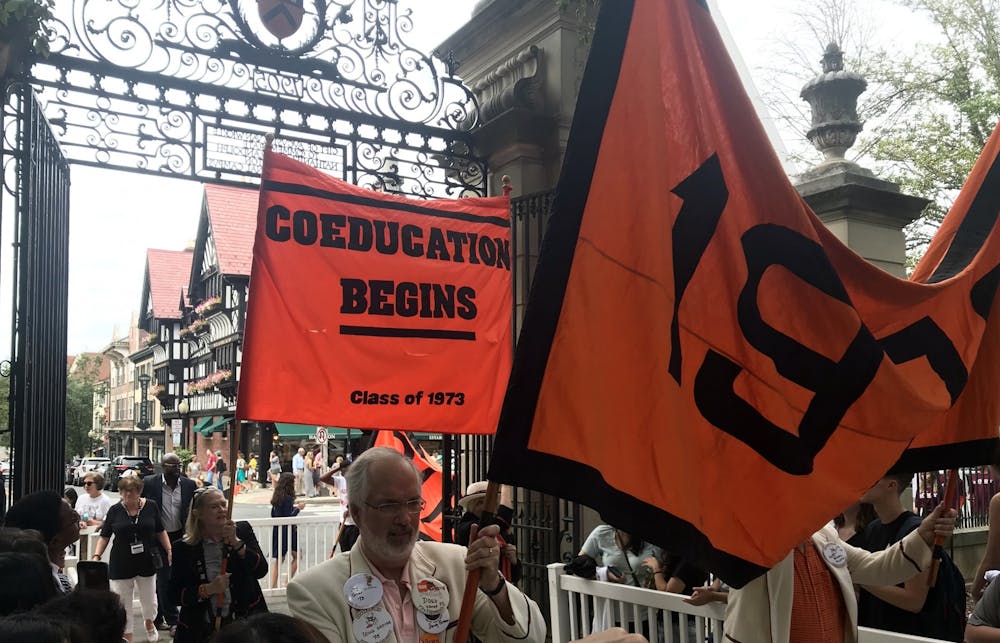

In 1969, a group of female undergraduates arrived on Princeton’s campus; in 1973, they became the first women to graduate from the University. This is the first installation in a series commemorating 50 years of women at Princeton. Each article will chronicle the experience of one woman from the Class of 1973 and one from the Class of 2023.

When Susan Belman ’73 transferred to the University as a junior in 1971, she knew her first weeks at Princeton would be unusual. She might not have guessed the extent.

Initially enrolled at the University of Rochester, Belman was one of the only female transfer students in Princeton’s first-ever class of women — and she spent her first 10 days on campus in a hospital bed.

“We dumped my stuff off at Brown Hall, and we went to the infirmary, where I was diagnosed with double pneumonia,” Belman recalls.

That may sound like a surefire way to ruin a transition to college. For Belman, it wasn’t.

“I had friends who had friends [at Princeton] who came to visit me,” she said. “And just by virtue of the kindness of strangers, I thought I’m really going to like this place.”

In her first three months on campus, Cassandra James ’23 has managed to avoid both McCosh Health Center and a lung infection. But she can relate to Belman’s experience in one aspect, at least: she, too, agrees that the people of Princeton are what made her adjustment to campus special.

“Everyone at Princeton is so passionate about something,” she said. “People here are willing set everything aside and go after what they’re passionate about, and that’s really inspiring to me.”

And while Belman and James agree about the power of Princeton’s student body, it’s important to note that the student bodies during their times on campus could hardly have been more different.

102 women matriculated with the class of 1973. Only 83 graduated. On the other hand, the Class of 2023 boasts 682 women; 50.9 percent of the class — the highest ever Princeton proportion — is female.

In addition to this demographic change, academic statistics have shifted significantly. Precisely zero of the women of the Class of 1973 were B.S.E. students; 42.6 percent of 2023’s B.S.E. candidates are female. And Belman, who graduated with a degree in English, couldn’t recall learning from a single female professor.

“There wasn’t much of an expectation of women being represented scholastically,” she said. “It was assumed that the professors would be male.”

James hopes to concentrate in the same department from which Belman earned her diploma 46 years ago: English. But all of James’s four professors this term are women, and a majority of the students in her classes are women as well.

It’s “pretty neat,” she said. “We have a lot of discussions in those classes about what it means to be a woman in relation to whatever we’re talking about.”

Belman, who came to Princeton from the co-ed University of Rochester, attended the University during a transfer student boom. During the 1960s, this paper recorded that “the number of transfer students accepted has not exceeded 10.” In 1971, Princeton accepted 171 transfer students: 56 men and 115 women. After 1980, the University barred transfers from applying for a year due to a lack of dorm space; application numbers began to dwindle. The University fully put an end to accepting transfer students from 1990 to 2018. Today, transfer students are few and far between, with only 13 students accepted in 2018 and 14 students in 2019, and only nine enrolling in each year.

Belman and James cited some of the same campus landmarks: acapella concerts under Blair Arch, the eating clubs of Prospect Avenue. But even if those architectural pieces have stood steadfast for 50 years, the culture surrounding them has undeniably changed.

Because Belman transferred as a junior, she joined an eating club immediately upon her arrival. Colonial Club — her choice — was one of the University’s 14 eating clubs, and one of just 10 co-educational ones in 1971. Tiger Inn and Ivy Club changed their all-male demographics only in 1991, after a lawsuit from former student Sally Frank ’80. In 2015, TI elected its first female president, and in 2018, nine eating clubs elected women as presidents.

And despite all the gender progress on Prospect Ave., one question has loomed equally over Belman’s time and that of James: to bicker or not to bicker.

“I joined Colonial because I’m sort of egalitarian,” Belman said. “I just didn’t like the whole notion of bicker.”

Neither, really, does James. Eating clubs, she said, aren’t really her scene — she doesn’t see herself going any time soon. James’s social experience comes mostly from her extracurriculars and the friends that she has made through theatre and music.

“I’ve specifically met a lot of really interesting women, upperclassmen in the arts, and also alumni who come back to campus,” James said. “I’m trying to meet people who are like-minded and who are interested in the things that I’m interested in.”

They may be 50 years apart, but Belman could have been one of those ‘like-minded’ individuals whom James hopes to meet. To Belman, her passion for English has as much to do with a love of reading as with “getting to know and analyzing characters and language.”

James echoed that, noting that she is considering a concentration in English because “writing gives the opportunity to tell your own story.”

Post-Princeton, Belman went on to become a lawyer, although she had originally planned to become an English professor. For James, her dream life would be “to be a novelist for either children or teens and to be traveling the world doing events for [her] books.” However, she also said that she’s open to exploring other options.

Belman’s only regret about her experience at Princeton? With only two years at the University, her time was too short.

“I had the most wonderful time at Princeton,” she said.

Hopefully, in four years, James will be able to say the same.