In the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs (WWS) “Undergraduate Program Viewbook,” Dean Cecilia Rouse refers to WWS as a “multidisciplinary liberal arts major for Princeton University undergraduate students who are passionate about public policy.”

Through an analysis of 75 years of alumni career data, The Daily Princetonian sought to examine how often this passion turns into a policy-based career, analyzing where WWS alumni professionally end up.

The examination of alumni career data, available in the TigerNet Alumni Directory, shows that while the WWS sends more students into government jobs per capita than any other major, a WWS graduate student is nearly seven times more likely than an undergraduate to go into government.

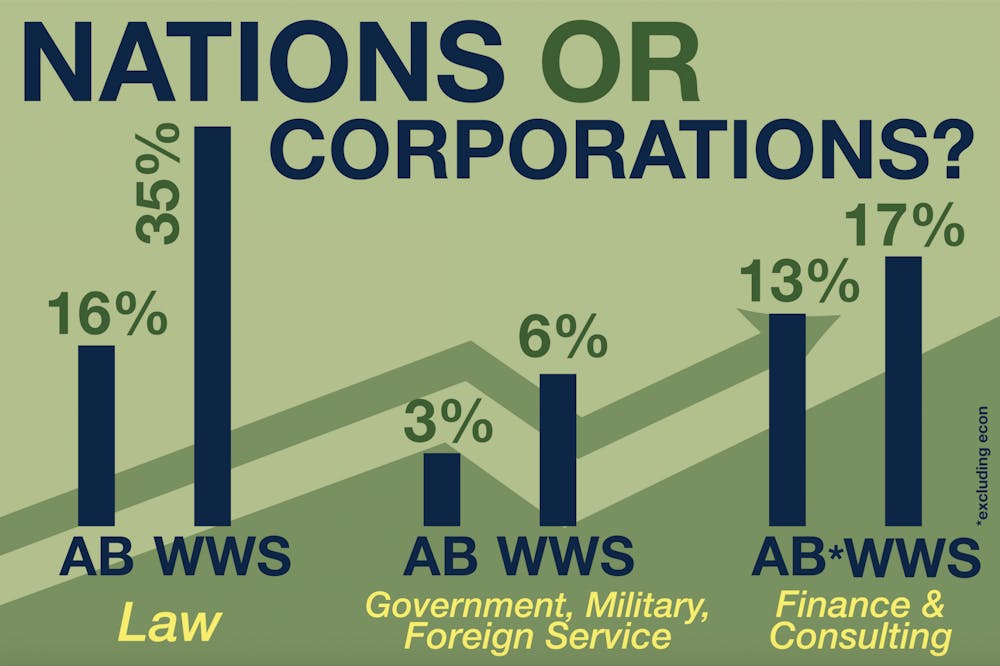

Additionally, comparing WWS majors to other Bachelor of Arts (A.B.) recipients, a higher percentage of WWS graduates go into finance and consulting than all but three other A.B. majors, and WWS sends more students into law than any other department.

According to the WWS website, alumni “become leaders in their respective fields,” and “[t]heir careers embody the University’s unofficial motto ‘Princeton in the Nation’s Service and the Service of Humanity.’”

Serving nations or corporations?

To examine how many students from each major were going into public administration or government-based service, the ‘Prince’ compared the number of students who listed “Foreign Service,” “Military,” or “Government” (including more specific classifications) as a “field/specialty” on their TigerNet profile to the total number of students who listed any field (“Other” included).

From all graduates from 1941–2016 with listed fields on TigerNet, there was a higher percentage of WWS students in government employment, foreign service, or military service than any other major, with 6.4 percent of WWS alumni listing one of those fields. Over that time frame, the politics department sent more total students, but only 5.5 percent of students. These compare to a 3.1 percent rate of government, foreign service, and military employment for A.B. students at large.

In terms of more specific time frames, WWS concentrators went into these governmental and service-related fields at a higher rate than students from all other departments from 1941–1969, 1980–1989, 1990–1999, 2000–2009, and 2010–2016. Students who graduated in the 1970s from WWS, however, were less likely than politics majors to go into public policy or foreign and military service. 2000–2009 represented the highest rate of employment in these fields from WWS concentrators (9.0 percent) and A.B. students at large (4.0 percent).

Though WWS sends more graduates into these public sector jobs than any other department, some alumni still wish the numbers were higher across the board. WWS graduate Magdi Amin ’88, who currently manages the “Beneficial Technology” department of a private-sector investment company, working on many of the same issues that public sector employees seek to address, wishes more University students sought out careers in the public sector.

“While I believe that one can serve the public good through the private sector, there is certainly a legitimate desire to see more students go into government,” he said. “More effective governments and capable institutions are good for everyone.”

Amin said he believes that trust in many public institutions, but notably government, has been in decline — but still sees ways forward to combat this perception.

“Current students may not have confidence that they will realize their ambition to have a positive impact on society through government,” he said. “It might help to create more exposure to senior civil servants who are having an impact in their respective fields.”

Jon B. Alterman ’87, Senior Vice President, Zbigniew Brzezinski Chair in Global Security and Geostrategy, and Director of the Middle East Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, pointed out certain barriers to entering direct government service, which he says have contributed to the aging population of government employees.

"One [barrier] which I have discussed directly with the Robertson family, is that direct government employment is becoming harder to secure,” he said. “Partly it's due to the rise of government contractors, but it's also because of periodic hiring freezes and budget uncertainty that makes a government career increasingly hard to secure.”

Additionally, in a 2019 ‘Prince’ piece on reasons why many WWS graduates do not go into service, various WWS undergraduates and alumni cited the disparities between public and private-center entities in both entry-level salaries and recruiting presence on campus.

University sociology and public affairs professor Jennifer Jennings ’00, a WWS alumna, pointed to the coercive nature of a six-digit salary. According to University reporting on class of 2017 job outcomes, the average student entering “Public Administration” earned an annual salary of $45,049. For students going into “Finance and Insurance,” that number nearly doubled to $87,753.

At the HireTigers Career Fair this past fall, 10 governmental and foreign service organizations, like the Federal Bureau of Investigation and Peace Corps, were present — but there was a substantially greater presence from Finance and Consulting firms, which accounted for 16 and 17 tables, respectively.

To examine how many WWS students were going into these two industries, popular fields among alumni, the ‘Prince’ compared the number of students who listed a “field/specialty” as “Consulting” or one of 12 finance-related options to the total number of students who listed a field or specialty across majors.

Of A.B. alumni who graduated between 1941–2016, 15.8 percent listed one of these fields. However, after removing economics majors (35 percent of the department listed these fields, accounting for nearly a quarter of all alumni in consulting or finance), the number drops to 13.5 percent.

Of WWS graduates from that same interval, 16.8 percent listed consulting or a form of finance as a field or specialty. Of graduates from 2010–2016, 21.5 percent of WWS alumni listed these fields, compared to 13.4 percent of non-economics A.B. students.

Over the total time-frame , WWS concentrators were more likely than alumni from all but three A.B. departments (economics, politics, and sociology) to enter one of these fields. However, the sample size of sociology was quite small (708 total graduates with fields listed, compared to 2,483 from WWS, 3,053 from economics, and 3,186 from politics).

WWS graduates from 1970–1979 and 2010–2016 were more likely than all other A.B.-receiving alumni, excluding economics majors, to list finance or consulting as a field.

Politics concentrators from 1980–1989 and 2000–2009 were more likely than WWS concentrators to list these fields. Still, for these time periods, WWS concentrators were over 3 percent more likely than non-economics A.B. alumni to list their field as consulting or finance.

The greatest discrepancy between WWS concentrators and non-economics A.B. recipients existed among graduates from the 1990s, among whom 19.1 percent of WWS concentrators listed finance or consulting as a field, compared to 9.2 percent for non-economics A.B. recipients.

In a statement to the ‘Prince,’ Rouse wrote that she thought WWS students “land in appropriate jobs after graduation.”

“The concentration is a liberal arts major, not a pre-professional course of study, so like students in all concentrations across campus, students land in jobs in the private sector, non-profit and government sector or go on to graduate school,” she wrote.

Alterman applauded what he called the Wilson School’s “multidisciplinary approach to problem solving,” something he thinks universities as a whole need more of. He said he thought the Wilson School prepared him superbly for what he does, and that we “should think of public service expansively” and “encourage more Princeton alumni to enter into it.”

“My classmates in the Wilson School have done all sorts of things since graduation. One runs a large auction house, one is a law professor, one is a physician, and one works on Wall Street. Two are career diplomats, and another runs the ACLU,” Alterman added. “I don’t think it’s a bad record, and I do think, on the whole, it amounts to being in the nation’s service.”

Bridget Akinc ’98, CEO of the non-profit Building Impacts, also highlighted the increasingly malleable boundaries that lie between the corporate, non-profit, and government sectors.

“With the recent emergence of B corporations and the August 2019 declaration of the Business Roundtable redefining the purpose of the corporation, the [nonprofit/for profit] distinction is less important — that is a matter of accounting. What matters more is the defined purpose of the organization,” Akinc said.

Undergraduates vs. Master’s

According to past WWS annual reports, over half of WWS graduate alumni from 2015–2018 entered “public or nonprofit” work directly after graduation. This statistic was highest in 2018, with 81percent of master’s recipients entering public or non-profit work.

Maya Hardimon GS ’21 emphasized the importance of considering the “public or nonprofit” statistics, saying that a large percentage of graduate alumni work at non-governmental organizations and “it’s important to recognize that ‘public service’ doesn’t necessarily need to take place in the public sector.”

For alumni who graduated between 2015 and 2018, WWS placed over 40 percent of master’s recipients specifically into the public sector. This statistic was also highest in 2018, when 52 percent of master’s recipients entered public policy.

“The vast majority of master’s students go to positions in the government or non-profit sector (which we define as public service),” Rouse wrote to the ‘Prince.’ “A much smaller number of undergraduate concentrators go into public service [compared to master’s students], but that isn’t surprising.”

The discrepancy in per-capita entry into government related jobs between undergraduate and graduate alumni was large. Among alumni with fields listed on TigerNet, 44.7 percent of graduate alumni listed foreign service, military service, or one of the “government” service options as a field or specialty, making MPA and MPP recipients nearly seven times more likely to enter these fields than their undergraduate counterparts.

This ratio has also grown gradually over time. Among alumni who graduated in the ’70s, graduate students were about twice as likely to enter these government-service-related fields (6.9 percent vs. 3.6 percent).

This ratio rose to 2.5 (21.3 percent vs. 8.4 percent) for alumni who graduated in the 1980s, and to 5.6 (36.7 percent vs. 6.6 percent) for alumni who graduated in the ’90s.

A rise in both graduate and undergraduate alumni entering governmental service in the 2000s kept the ratio at 5.5 (49.6 percent to 9.0 percent), but among graduates from 2010–2016, 60 percent of MPA and MPP recipients entered government-service-related fields, compared to 7.1 percent of undergraduates (yielding a ratio of 8.5).

Where the percentage of WWS undergraduates going into government-related fields has fluctuated over decades, rising from under 4 percent before the 1980s and fluctuating around 6–8 percent after then, the percentage of MPA and MPP recipients entering these fields has risen over time (a steady increase from 7 percent to 21 percent go 37 percent to 50 percent to 60 over the measured time intervals).

In addition to the curriculum, Hardimon said the WWS’s financial support plays a role in allowing graduate students to pursue careers in government, political advocacy, NGOs, and other service-based industries.

“Compared to students at a lot of other policy schools, we don’t face as much pressure to take high-paying private sector jobs in order to pay off massive student loans,” she noted.

Undergraduate WWS alumni are also somewhat more likely than Master of Public Affairs (MPA) and Master of Public Policy (MPP) recipients to go into finance or consulting, though the discrepancy in these fields is far smaller than in government. Of alumni who graduated between 1941 and 2016, 12.5 percent of MPA and MPP recipients listed finance or consulting as a field or specialty, compared to 16.8 percent of WWS undergraduates.

WWS as a pre-law major

More WWS concentrators listed “Law” as their field or specialty than any other undergraduate department, and WWS undergraduates are more likely to go into law than their graduate school counterparts.

Karolen Eid ’21, with her experience as Publicity Chair of Princeton’s Pre-Law Society, confirmed that these statistics parallel her interactions with prospective law students on campus.

"Most of the pre-law students I meet are [majoring in the] Woodrow Wilson [program], history, or politics," she said.

Eid is a staff writer for the ‘Prince.’

Of the 73 upperclassmen on the Pre-Law Society listserv, 22 are declared WWS concentrators, amounting to 30 percent of the group. Additionally, 14 percent of that group is made up of politics concentrators, 11 percent of history concentrators, and seven percent of philosophy concentrators. Seventeen separate majors account for the remainder of the 73 students, with no more than three students concentrating in a single major.

As a Woodrow Wilson student on the pre-law track herself, Eid illuminated some competing interests that students feel which could explain this widespread orientation toward a legal career. On one hand, she says she often hears students worried about attaining “financially security.” At the same time, she noted a student culture which “pushes” students toward careers with a public service focus and away from the private sector.

Out of graduates from the class of 1941 to the class of 2016, 30.6 percent of WWS concentrators listed law as a field, compared to 14.7 percent of A.B. recipients at large. Over this time frame, the politics department produced the most law specialists in total, though approximately 5 percent less lawyers than WWS.

WWS undergraduate alumni were also about 5 percent more likely than graduate school alumni to list law as a field (30.6 percent vs. 25.7 percent).

Due to the likelihood that graduates from 2010–2016 may not yet have completed law school, the percentages for that interval is significantly lower, with less than half of those from each other interval. Removing this interval from the sample, 35 percent of WWS concentrators went into law (compared to 15.9 percent of A.B. recipients).

The 1970s produced the most lawyers per capita for both WWS concentrators and A.B. students at large, with over half of WWS alumni (50.6 percent) and 16.2 percent of A.B. alumni listing a type of law as their field.

The sample also showed no major deviations between WWS concentrators and A.B. recipients at large when it came to types of law.

The WWS department accounted for 20.3 percent of A.B. recipients who listed their field as corporate law, 20.4 percent of those who listed criminal, and 18.7 percent litigation. For comparison, of alumni who listed a specific legal field, WWS alumni accounted for 18.9 percent.

Less common types of law deviated further from 18.9 percent, but this may be attributable to sample size. WWS students accounted for 11.8 percent of intellectual property lawyers, 8.2 percent of patent and copyright lawyers, 21.8 percent of tax lawyers, and 13.1 percent of trust and estate lawyers. However, sample sizes among these subcategories ranged from 55 to 122 (compared to 946 corporate lawyers and 961 litigators).

Methodology:

The ‘Prince’ analyzed career outcomes based on what alumni listed as their “field/specialty” on their alumni profiles, available on TigerNet. The website allows alumni to list up to two fields, out of 75 total options including “Other.”

The percentages for specific fields, as they appear in this article, were found by dividing the number of profiles with a specific field listed by the number of profiles that listed a field, disregarding profiles of alumni with no field listed. Assuming that tendency to fill out a TigerNet alumni profile in its entirety does not correlate with tendency to pursue any specific career, the sample used is unbiased.

The sample is also relatively large. Of the total profiles for alumni who graduated between 1941 and 2016, 49 percent have filled out fields or specialties. Overall, this interval included 58,724 alumni profiles and 4,824 WWS alumni specifically. The starting year of 1941 was chosen because there were no Wilson school alumni with fields listed who graduated prior to 1941.

We chose 2016 as the last year to analyze because many of the more recent alumni did not have entirely filled out alumni profiles (57 percent of graduates from 2010–2016 had a listed field compared to 11 percent among graduates from 2017–2019). The number of A.B. graduates with a field listed ranged from 3,529 for the 2010–2016 interval to 5,960 for the 1990s.

When recording the aggregate data from TigerNet, the search mechanism made it such that cases of alumni who received both an undergraduate degree from the University and a graduate school degree from WWS may have caused duplicates, depending on when the degrees were received and whether both degrees were received from WWS. The ‘Prince’ individually removed each duplicate prior to analyzing the data.

Because alumni were permitted to list more than one “field/specialty,” the ‘Prince’ chose to analyze combinations of certain fields rather than individual fields themselves. For example, we chose to look at “Finance and Consulting” as a singular entity because a number of alumni listed both “consulting” and a form of finance as their specialties. Searching instead for alumni profiles that list finance or consulting as a field accounted for this overlap.

The twelve “Finance-related options” that TigerNet allowed alumni to choose were Asset Management, Corporate Finance, Hedge Funds, Investment Management, Private Equity, Commercial Banking, Financial Planning, Investment Banking, Securities/Commodities, Tax Trust and Estate Finance, Venture Capital, and “Finance-Other.” By combining these fields and, again, combining them with “consulting,” the ‘Prince’ accounted for overlap.

For this same reason, the ‘Prince’ listed conducted analysis on the percentage of alumni who listed a field as government work, foreign service, and military service as a singular entity. “Government work” here includes eight specific “fields,” all of which overlapped fairly frequently. These fields, all proceeded by a “Gov.-”, include work in Departments and Agencies, work in “politics” generally, and work as a Cabinet Member, Legislator, Executive, Policy Analyst, or White House Staffer, as well as a “Gov.-Other” field.

The TigerNet Alumni Directory also allowed alumni to put “law” into more specific terms, with corporate law, criminal law, trust and estate law, intellectual property law, litigation, patent and copyright law, and tax law all listed as possible fields, in addition to a “Law-Other” option.

When referred to generally as “law,” the sample includes all of these fields. When listing percentages for specific types of law, the sample disregarded alumni who listed “Law-Other.” For the entire interval (1941–2016), WWS students accounted for 18.2 percent of those who listed “Law” and 18.9 percent of those who specified beyond “Law-Other.”

Additionally, only juniors and seniors were considered for determining the number of students from each major in the Pre-Law Society because A.B. students do not declare majors until the end of sophomore year.

For the comparisons between WWS undergraduate and graduate alumni, the interval from 1941–1969 was disregarded because very few WWS Master’s recipients who graduated prior to 1970 had filled out alumni profiles.