Matthews Theatre, in the McCarter complex, transforms into a haunted playground for humans and monsters alike. There is no telling who or what might suddenly leap from a balcony or crawl out from under the floor. Unsuspecting audience members may be thrust into the spotlight. But most unsettling is the way the lines blur between human and monster and between reality and nightmare in Lookingglass Theatre Company’s production of “Frankenstein.”

So many reinterpretations have breathed new life into Mary Shelley’s 19th-century monster that it is easy to forget where the character came from. But the story of Mary Shelley’s life as a 19th-century female author who rejected the institution of marriage in favor of free love captures the imagination almost as much as her world-famous novel. The 2017 film “Mary Shelley” marked a revived public interest in the writer’s radical and tumultuous personal life. Lookingglass Theatre Company sees no reason to discriminate between the life of the author and those of her characters but rather weaves them irrevocably together.

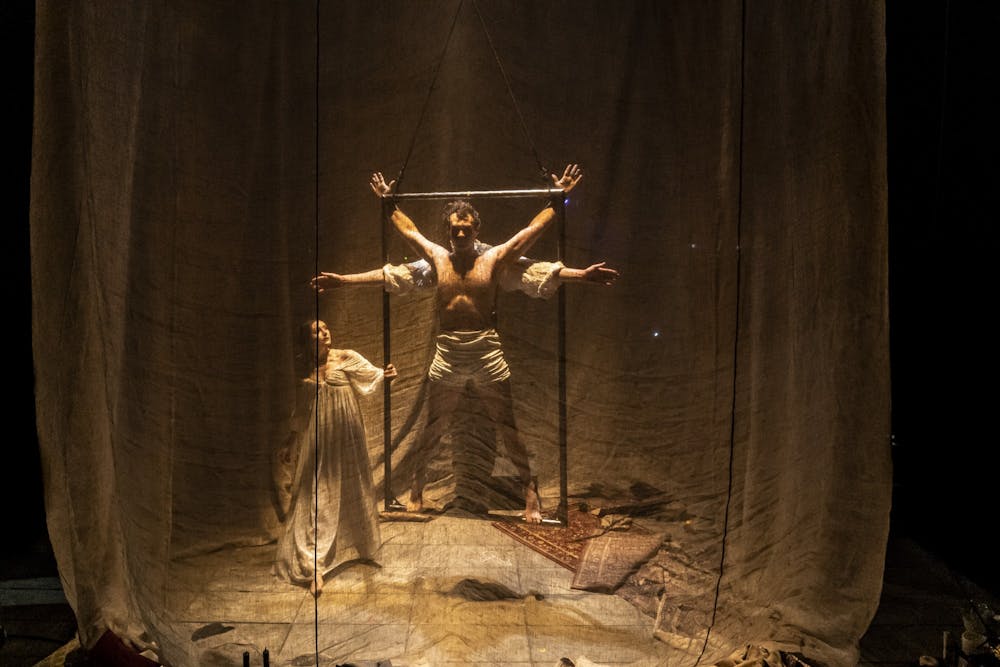

Mary Shelley and a small group of friends and lovers, separated from the McCarter audience by a thin veil, begin the show playacting a ghost story by candlelight. Under Mary’s direction, they put a new spin on the tale of the ambitious Victor Frankenstein, a young man compelled by his mother’s death to seek out the secret of reanimating the dead. His ultimate success only brings him more death and calamity. Frankenstein abandons his grotesque creation, who proceeds to wreak revenge. Yet the “monster” Frankenstein creates comes to display the most human characteristic: a desire to love and be loved. In denying him the possibility of companionship, Frankenstein reveals himself to be the true monster of the story, not its hero.

As the veil lifts from the stage and the performance spatially unravels into the audience, Mary Shelley’s traumas get tangled up with those of her characters. Mary Shelley and her lover, Percy Shelley, act out the fraught romantic relationship between Elizabeth and Victor Frankenstein. As Frankenstein holds his newborn baby brother in his arms, the swaddled figure becomes the child Mary and Percy have to bury. The overwhelming loss and betrayal of Frankenstein’s story echoes the real tragedies of the Shelleys’ own lives. The Shelleys would go on to lose several more children, and Percy himself would reach an untimely end out at sea – a fate his character, Frankenstein, only narrowly avoids.

In the closing scene of Lookingglass’ “Frankenstein,“ Mary’s friend Lord Byron asks her whether they are still in her ghost story, or if they have returned to real life. By this point, the audience is wondering along with him. As Mary goes on to direct the fates of all of her companions, audience members audibly gasp or even chuckle. Mary breaks through any distinction between reality and fiction. When we ultimately watch her meet her own ending, her death comes as her words finally fail her.

For all the other impressive feats of this production – full-bodied expressions of emotion, eerily beautiful singing, aerial acrobatics, innovative set design, and more – its greatest achievement is the convolution of the imaginary and the real, of narrating and living. Just as Frankenstein’s creation returns to haunt his life, Mary Shelley cannot unravel her life from the story of her invention.