When Amy Wax, a discredited professor who proclaims the alleged superiority of white culture, speaks at Whig-Clio tomorrow, it will be over the objections of many students, myself included. I believe that Whig-Clio, an institution that serves all Princetonians, should not host a speaker whose racial prejudice offends many students and precludes meaningful conversation.

Forty-six years ago, students wrestled with a similar, though far more incendiary, quandary after Whig-Clio agreed to host a debate between Roy Innis, then-director of the national Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and William Shockley, a eugenicist who believed that race determined intelligence and a 1956 Nobel laureate in physics. Whig-Clio invited both men after their previous face-off, to be held at Harvard, was canceled, amid fear of student outrage.

Wax and Shockley’s pseudo-scientific philosophies — so-called “cultural-distance nationalism” and “retrogressive evolution,” respectively — are not equivalent, racist and repugnant though both are. In fact, Wax has cited her criticism of cultural, rather than biological, difference, as a defense against charges of racism.

Nonetheless, examining how students reacted to the 1973 Innis-Shockley debate, which roiled campus for weeks, should inform our ethical assessment and collective response to Whig-Clio’s invitation to Wax today.

Shockley’s views were undeniably racist and eugenicist. Among other heinous measures, he endorsed voluntary sterilization for individuals with an IQ below 100. He repeatedly declared, “the major cause of American Negroes’ intellectual and social deficits is hereditary and is racially genetic in origin.”

Several days before the debate, six black faculty members urged students to boycott Shockley’s event. On Dec. 4, the day of the debate, the Association of Black Collegians (ABC) published their own letter, “Un-thinking exercises,” in The Daily Princetonian. The ABC, a dynamic campus group that occupied New South in 1969, wrote, “The confrontation between Roy Innis and William Shockley sponsored by Whig-Clio and Princeton University is nothing more than an explicitly parochial perversion of the term academic freedom.

“The intelligence, humanity and creative essence of black people is a fact. The issue is not debatable because there is no question to be answered. Realizing these facts, one must question the motives of the university and Whig-Clio for sponsoring the event.”

Substitute “Wax” for “Shockley,” and the argument remains remarkably watertight.

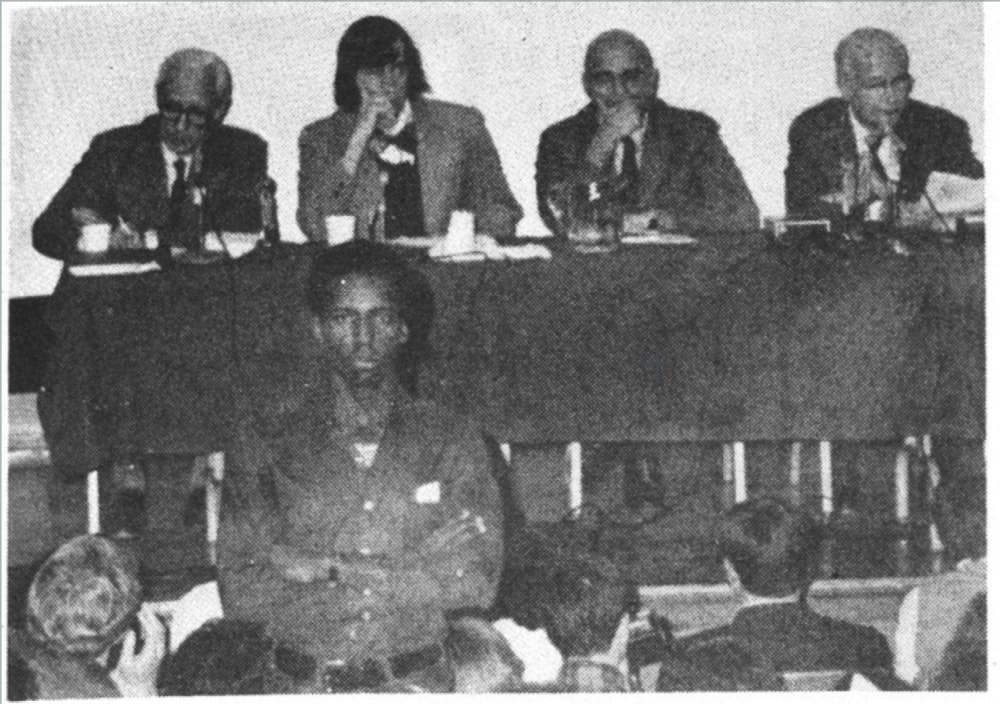

At 11:52 a.m., four hours before the debate, Innis backed out, notifying Whig-Clio via telegram that the University’s “social elitism and dangerous intellectual isolationism” precluded his participation. Yet, the event proceeded, with University anthropologist Ashley Montagu taking Innis’s place.

As 403 people trickled into the auditorium, an equal number of protestors, convened by the ABC, the University Action Group, the Asian American Students Association, and the independent Attica Brigade, chanted and marched in the McCosh courtyard. In front of television cameras, students burned an effigy of Shockley.

Last Saturday, at the protest against “Double Sights,” a sculptural installation meant to reflect Woodrow Wilson’s complicated legacy, Larry Adams ’74 reminded us of the conviction that drove him and his peers to demonstrate. He declared, “I am proud, as an individual, as a representative of the Class of ’74, [to have] stood against William Shockley’s denunciation of our humanity — right over there — when I was here.”

Anticipating unrest, Nassau Hall deployed more than 50 security officers for the debate. When thirty Attica Brigade protestors attempted to storm the entrance, a physical scuffle erupted; several minutes later, the University received a bomb threat. These incidents notwithstanding, the vast majority of students demonstrated peacefully.

In a Nov. 28 letter condemning the invitation to Shockley as a “publicity stunt,” M. Krishnan, then a graduate student, observed, “Whig-Clio has a tradition of never once having called a debate because of objections from any group.” As Krishnan correctly noted, Whig-Clio leaders did not deign to consider disinviting Shockley.

Last semester, the decision of two Whig-Clio leaders to belatedly disinvite Wax from an event drew the ire of some conservative Princetonians, who felt that her disinvitation violated Whig-Clio’s tradition of free and open ideological discourse. Yet, by insisting that Wax return, such students pledged the same blind allegiance to Whig-Clio’s archaic custom of refusing to renege on speakers, no matter how abhorrent their views.

In his own defense of Shockley’s invitation, then-University President William Bowen GS ’58 wrote, “Whatever the circumstances, the university must remain a place where even the most heretical ideas can be discussed.”

Forty-six years later, it seems that Whig-Clio has yet to entertain the most heretical idea of all: listening to all students, particularly those of color, as the institution determines who deserves its vaunted podium.

Jon Ort is a Managing Editor of The Daily Princetonian. This piece represents the views of the Managing Editor only. He can be reached at jaort@princeton.edu.