When I was 16 years old, I painted a portrait of Isaac Newton and hung it in my room. Every night that I would have to study for math or physics, I looked up at it for inspiration. As one of the great minds of the Scientific Revolution, his image motivated me to strive in those subjects to finally become a physics major. The portrait still hangs in my dorm today, and while it got me through high school physics, it doesn’t quite have the same effect now that I’m in college.

Princeton has an unusual portrait problem. Recently, the University unveiled four new portraits of distinguished alumni and faculty, with the intention of hanging them in “prominent places” around campus. But portraits are rarely featured in important or popular spaces around campus. Sure, you might have seen one or two, but they’re always tucked away in corners that receive little traffic from students, and they often depict donors (frankly, rarely inspiring figures) who do not attest to the diverse and accomplished legacy that this institution really has.

Princeton should be conscious about the message it sends through its iconography, and the first step to this is to make it more accessible, and to show faces that matter in places that matter.

The newly unveiled portraits are important dedications, but they have been placed in completely irrelevant locations that will not promote these inspiring members of our campus community. The portrait of Alan Turing, the father of computer science and an important figure in LGBTQ+ history, will be hung in the atrium of Lewis Library. One would think that such an important figure deserves a place more suitable than the bleak walls of a building whose architecture doesn’t really favor wall fixtures. Why can’t we place him in a prominent place in the Rocky-Mathey Dining Hall, in the Fine Hall lounge, or in one of the frequently-visited common rooms around campus?

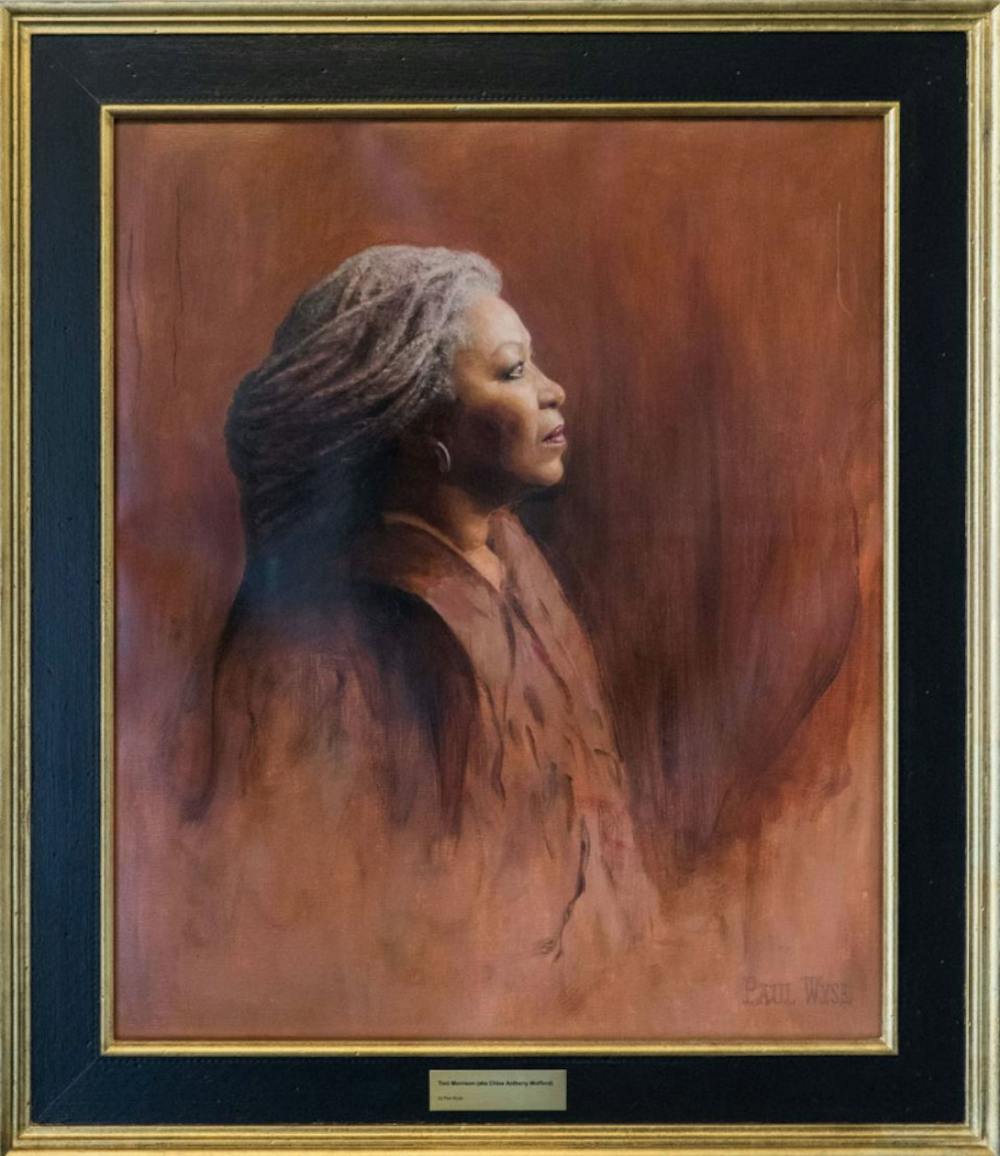

Another portrait, of Carl A. Fields, namesake of the Fields center and the first African-American administrator of the University, will be relegated to a minor entryway in Morrison hall, sharing the fate of Paul Wyse’s excellent but underappreciated portrait of the transformative Toni Morrison. Despite being housed in the building which bears her name, her visibility is reduced — though I suppose she will now enjoy the company of Dr. Fields.

When I was talking to one of my friends, an exchange student from Oxford, he told me about the wealth of iconography spread around his college, and not just in dark narrow hallways of obscure administrative buildings, but in the spaces where students lived and spent most of their time. The dining hall of Hertford College is covered with illustrious figures of its past and present, such as a prominent portrait of William Tyndale, the first person to translate the Bible into English.

These ever-present faces are an important aspect of the daily life of Hertford students; they are not only fixtures in the wall, but they live in the community and remind students of what they can achieve. Almost all portraits currently existing in the University are either tucked away in the Faculty Room of Nassau Hall (which is not open to students), misplaced in obscurity, or simply depict subjects who have contributed nothing beyond a monetary gift.

Portraits are a powerful form of art. As a portrait painter, I have contemplated such questions, which go beyond pure artistic skill, when creating one. Portraits possess a fundamental essence and potential for communication, which far supersedes words: the face of wise figures from the past, the way they look at you, how their eyes seem to shine as if they were about to reveal great secrets to you. These are the great and deliberate effects that portraits have on us.

University students in the search for meaning in our work — meaning that goes far beyond getting a profitable job or a stable position — need to see the faces of those who have found that meaning. When we have seen their faces, we will learn their stories, and their portraits will be a permanent reminder of the careers they undertook, the barriers they crossed, the people who stood in their way, and how they prevailed.

We all need inspiration, and while these portraits may not move and talk like the fabled images at Hogwarts, they can certainly speak to us in a more fundamental, transcendental way. They stand before us as witnesses of their triumph, and they offer us a chance to share that destiny.

Juan José López Haddad is a sophomore from Caracas, Venezuela. He can be reached at jhaddad@princeton.edu.