Athletes from rich towns are siphoned into elite colleges

The fraudulent college admissions scheme that the FBI uncovered this past spring shocked the nation. Parents who were bankers, celebrities, and lawyers got their children into top colleges — including Yale — by buying slots on coaches’ recruitment lists.

But the scandal raised larger questions about the role of athletics in higher education and who benefits from them. “Sports recruiting is the real college admissions scam,” Slate declared.

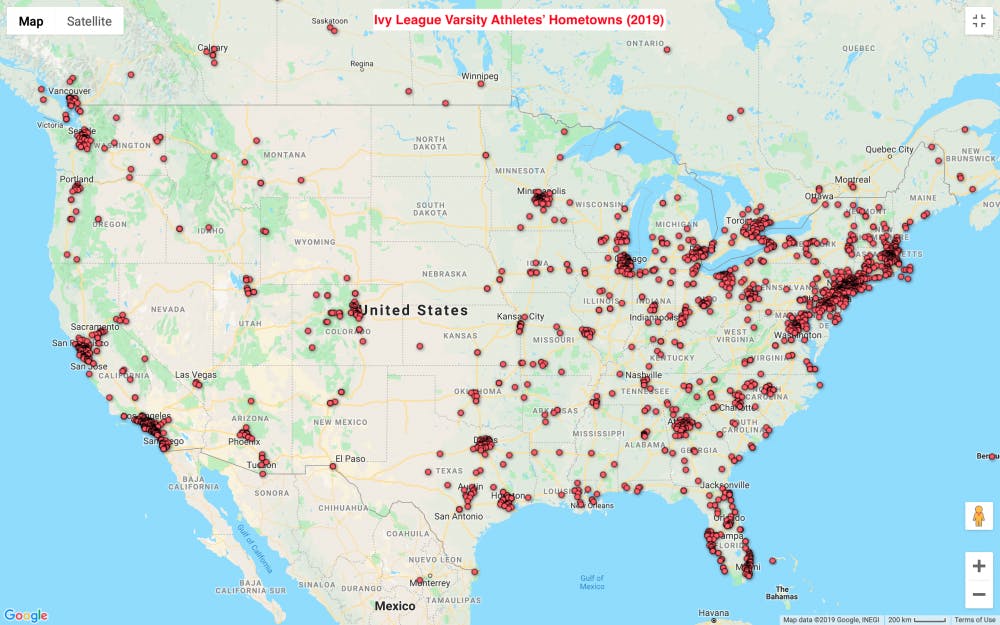

I dug into the online 2019 team rosters for all eight Ivy League universities to see who’s playing for them and where they came from.

The vast majority were likely recruited. The Daily Princetonian previously reported, “recruits dominate the rosters of the other 33 varsity Princeton teams [besides rowing], which typically include one to two walk-ons.”

My results show that sports pump hundreds of students from America’s richest towns and private “feeder schools” into elite colleges.

Cities

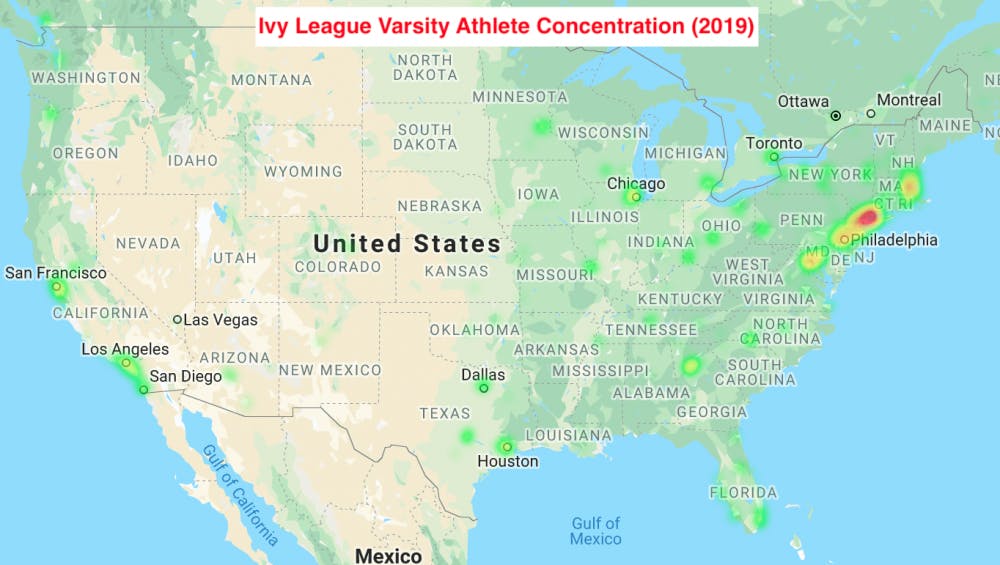

The homes of the Ivy League’s more than 7,000 athletes were clustered around the suburbs of major cities. They mostly lived in the Interstate 95 Corridor, which extends from Washington, D.C. to Boston. Other hotspots included Atlanta, Chicago, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. One in 10 American players lived in a hometown featured on Bloomberg’s 2018 list of “100 Richest Places.”

Concentration of Ivy League varsity athletes along the I-95 Corridor.

Connecticut’s Gold Coast had the highest concentration of athletes of any area in the U.S. One hundred and ninety-five came from lower Fairfield County, a third of whom were Greenwich residents alone. Rowing was the most popular sport there, followed by squash.

Not to be outdone too easily, Boston and the North Shore’s 15 richest suburbs sent 185 athletes, with Wellesley, Massachusetts — whose median household income is $176,852 — as the leading contributor.

Northern Virginia provided 117 athletes. McLean and Alexandria — two of the state’s wealthiest towns — were tied for having the most in this region. Maryland’s affluent D.C. suburbs also slam-dunked students into athletics. Bethesda sent 29; Potomac, 16; and Chevy Chase, 15.

Ninety-three athletes resided in the 10 towns of Westchester County, New York, that were featured on the Bloomberg list, all of which had average household incomes above $196,000. Philadelphia’s Main Line sent another 87, and Chicago’s North Shore suburbs sent 59.

The top 10 towns in San Mateo and Santa Clara Counties, California, were home to 60 and 53 athletes, respectively. Orange County’s highest 10 income towns also sent 53.

National distribution of hometowns of Ivy League varsity athletes.

Rich suburbs gave the Ivy League a disproportionately large share of its athletes, but cities still reigned in some cases. New York City was home to 151 players; Los Angeles, 64; and Houston, 49.

Only two athletes lived in either North Dakota or West Virginia, and four athletes in either Wyoming or Mississippi.

London, United Kingdom, was the most popular foreign city for finding athletes. It sent 75, almost half of whom were rowers. At 46, Toronto, Canada, was the next most popular place abroad.

High Schools

Team rosters also showed that private high schools funneled dozens of athletes into the Ivy League.

The Noble and Greenough School (annual cost: $58,100 for boarding students) had 50 alumni as varsity athletes. Deerfield Academy ($60,680) came in second with 36 students; Phillips Exeter Academy ($55,402), third, with 32; and the Lawrenceville School ($66,360), fourth, with 30.

Noble and Greenough’s Communication Office didn’t respond to my request for comment.

One out of every seven British athletes attended Eton College ($51,324) or St. Paul’s School ($47,378), of whom the majority were rowers.

Greenwich High School topped the public school list with 32 athletes. Newport Beach’s Corona del Mar High School and the Chicago North Shore’s New Trier High School tied for second at 21. Other notable top public schools whose contributions occupy the high teens include Princeton High School, Weston High School, Darien High School, and Manhasset High School.

At least 11 private high schools had 20 or more seniors who became athletes, versus just three public schools.

“It’s frankly not surprising to me that our students are going to come from the Northeast and come from places with good high schools,” Ivy League Executive Director Robin Harris said in a phone interview. She emphasized that private high schools are providing financial aid and diversifying their student bodies. According to her, it’s difficult to make assumptions about why some students go to certain schools.

“Our coaches can recruit. But it is each individual school’s admissions office that determines whether or not a recruited prospective student-athlete will be admitted,” Harris said.

She declined to comment when asked about 2018 Harvard court filings showing that recruited athletes with relatively low academic credentials were 1,000 percent more likely to be admitted than non-athletes.

Thomas Espenshade and Sarah Levin Taubman — co-authors of major studies involving athletics in admissions — respectively declined to answer and did not respond to my requests for comment.

Regional Trends

Not all sports are played across the entire country. Some are confined to particular regions. I calculated median centers of population to track these trends.

Women’s golf, men’s volleyball, and water polo for both genders were the most western sports. They were each centered in Los Angeles. Men’s squash, men’s hockey, men’s tennis, and men’s heavyweight rowing were clustered in the northeast, around northern New Jersey or New York. Fencing was split between the coasts.

Women’s soccer, women’s softball, and women’s volleyball were the sole sports based in the southern states, though men’s football also had a strong southern contingent. Polo players were concentrated in the northeast. Not a single skier came from the South or the Great Plains. Canadians composed a third of hockey players.

Columbia had more western athletes than any of the other Ivy League universities, as its center was near Jacobsburg, Ohio. Yale and Princeton were not far behind it, straddling Marianna, Pennsylvania. Penn’s teams were the most eastern, and Brown was the most northern.

Still, the centers showed that athletes predominantly came from the east coast, specifically New England and the Mid-Atlantic states.

“There’s no other conference in Division I that has broad-based sports sponsorship as a commitment to the benefits that sports provide student-athletes and the campus,” Harris said.

The Big Picture

A lot of research has dug into Ivy League athletics over the past twenty years, so I’ll put my findings in context.

Nationally, families spend thousands of dollars for their children to specialize at specific sports at an ever-younger age with the expectation that they’ll be college athletes, NCAA research shows.

Ivy League schools offer over 30 sports for men and women, which is often more than what’s available at “powerhouse” schools. College Factual reported that the University of Alabama had 640 student-athletes in 22 sports. Last spring, Princeton had 920 in 37. The Harvard Crimson found that Harvard spends $1 million per year on recruitment expenses alone.

Athletes still have to submit the same Common Application forms as everyone else, but coaches can give them advice, as occurs in Cambridge. Final contenders make it onto lists that coaches submit to the admissions office. Daniel Golden wrote in The Price of Admission that mediocre athletes often get on their lists, pleasing wealthy parents who then donate money for new facilities.

Former Dean of Admissions Janet Rapelye denied that Princeton gives preferences to athletics when asked by an applicant in a New York Times blog. “We do not emphasize one activity over the other; athletics as well as artistic endeavors are equally regarded,” she said. Yet two comprehensive admissions studies — co-authored by Professor Espenshade in 2010 and former president William Bowen GS ’58 in 2003 — proved that athletes enjoy enormous admissions advantages.

“I was constantly peeved by athletic admissions. I thought they brought down the quality of the applicant pool,” a former Dartmouth admissions officer told Business Insider. Bowen and Levin also found that the majority are admitted with SAT scores below those of non-athletes.

About a fifth of the seats in each incoming class go to recruited athletes. Most of them don’t play high profile revenue-generating sports like football or basketball. They play the “country club sports” of polo, sailing, squash, rowing, and fencing, among others. Many of these sports are limited in their regional extent.

Athletes disproportionately come from private high schools — usually in the northeast. The high schools with the most Ivy League athletes are the same schools that send the most students to Harvard and Princeton as featured on PolarisList, except for those with academic admissions tests like Stuyvesant and Thomas Jefferson High Schools.

The Crimson’s survey revealed that nearly half of recruits in the Class of 2022 came from families earning more than $250,000 per year. Less than 13 percent of their families have annual paychecks under $81,000. NCAA data say that 65 percent of athletes are white, a higher proportion than many of their student bodies.

In college, Bowen and Levin found that athletes lagged in their studies behind what their high school academic scores predicted, and this underperformance continued into the off-season when physical exhaustion was not an issue. Walk-ons and non-athletes didn’t suffer from the same poor scores.

Despite this dismal record, colleges pour more money into athletics than any other extracurricular activity. At Princeton, the athletics department received $32.3 million last year. That’s $12.1 million more than the average academic department if they evenly split their funds.

An athletic divide pervades social life. Two-thirds of the Tigers’ athletes are in three eating clubs out of eleven total. They are more likely to be in Bicker clubs than non-athletes, and specific teams feed into socially prestigious clubs.

The Harvard Crimson and the Yale Daily News reported that Wall Street firms recruit dozens of athletes into high paying jobs through their networks of alumni who were athletes themselves. Presumably, a number of their children in the future will want to play sports at their parent’s alma mater or somewhere similar.

The cycle repeats itself.

Analysis

How many more studies, scandals, and investigations does the Ivy League need before it realizes that it has a problem? Athletic recruitment is building an eastern aristocracy.

America’s upper echelons are using recruitment to secure their status for the next generation. Most elite college students worked hard to get their places, including athletes. But some students’ applications reach the acceptance pile more quickly and more often than others for the simple fact that a coach says they play a sport well.

It’s true that athletes’ geographic backgrounds closely match those of Princeton overall. Therefore, an athletic director could argue that my findings aren’t a problem because athletes are representative of student bodies.

The difference, though, is that coaches actively seek out students in recruitment. They’re basically doling out golden tickets of acceptance to the wealthiest families, whereas the rest of admissions — ignoring its own flaws for a moment — is at the mercy of varying regional application rates. Athletics is one reason why upper crust schools like Exeter and Nobles have so many students who go to elite colleges.

The Ivy League is by definition an athletic conference. But it can’t forget that its colleges are eight of the best institutions of higher education that train the world’s ruling class. Athletes should continue to be a part of the Ivy League. Recruitment should not.

Reform must come from the top down. A president sits at the helm of a university’s machinery and knows enough key players to build momentum behind his or her campaign. Action from a single school would result in utter failure, as its teams would perennially lose to rivals.

Success is only possible if the Ivy Presidents act together. They must be willing to stand up to the ensuing tsunami of backlash from alumni, coaches, parents, and students. Let’s not wait for another scandal. The time for change is now.

Methods

I’ve written several columns critical of varsity athletics in recent months. I don’t single them out due to a grudge against athletes. Rather, it’s simply the group with the most available public data. If legacies and development admits were posted online, I’d write about them too.

I acquired varsity rosters from colleges’ athletics websites and mapped hometowns in Google Fusion Tables. The statistics that I mention ignore international students unless otherwise stated.

Individual sports’ median centers of population are calculated only from Princeton’s rosters to sidestep the universities’ reporting differences. For example, the Tigers have lightweight and heavyweight rowing. Brown simply lists “rowing.” Princeton’s trends hold across the league. Water polo is still a western sport, and skiing isn’t becoming southern any time soon. I ignored cross country because its roster highly overlapped with track, causing a pattern affected by two-sport athletes. Other sport-specific statistics refer to the whole Ivy League.

Bowen and Levin found that a lot of athletes drop varsity sports after their underclassmen years. Numbers for individual schools are likely higher than reported because my data doesn’t count those who quit.

Although Smidge the Dog, a Labrador golden retriever, is listed as a “veteran” of Dartmouth’s equestrian team — and has her own varsity profile page — I didn’t count her as an athlete.