The University Library recently opened a new exhibition in the Ellen and Leonard Milberg Gallery, titled “Gutenberg & After: Europe’s First Printers 1450–1470.” Curated by Scheide Librarian Paul Needham and Curator of Rare Books Eric White, it is the first exhibition to focus on this early period of European printing, featuring loaned items from the United Kingdom never before seen in the United States and items from U.S. collections displayed outside their home libraries for the first time.

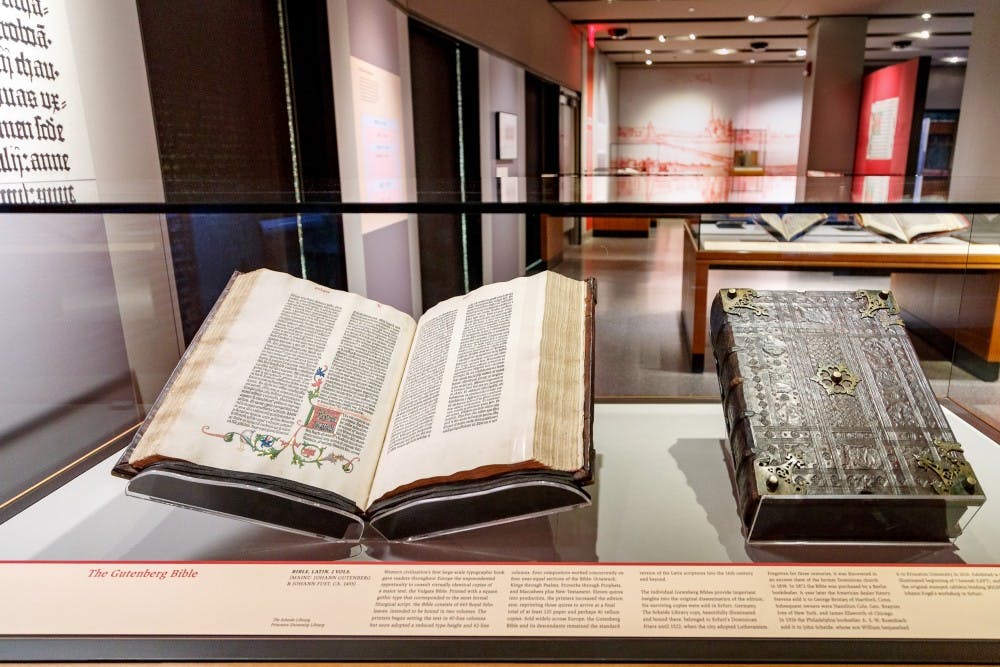

The exhibit grew out of the rare book collection of William “Bill” H. Scheide ’36, who bequeathed his personal library to the University in 2015. The Scheide Library contains some of the world’s finest artifacts related to early European printing, including the Gutenberg Bible of 1455 and the 1457 Mainz Psalter, two of the world’s earliest datable books.

“We thought once the bequest was finalized it would be good to have some kind of an exhibition when the new exhibition gallery was open — because [the gallery] was under renovation [and] construction for some years — to do something honoring Mr. Scheide’s gift,” Needham said. “Rather than just selected treasures from all the areas of his collecting, we thought that concentrating on earliest printing, which is where he had made really incredible acquisitions adding on to his father’s … would maybe have more intellectual integrity than just high spots.”

While exhibits honoring Johannes Gutenberg — the German man credited with creating the printing press in Europe — and early European printing have been mounted before, “Gutenberg & After” marks the first exhibition focusing closely and comprehensively on the first two decades of European printing. Rather than tracking the development of printing over a broad period of time or wide historical context, the curators chose to highlight printing accomplishments and innovations specifically within the early years.

The 1455 Gutenberg Bible from the Scheide Collection.

Photo credit: Shelley Szwast / Princeton University Library

In order to provide a comprehensive look at the first two decades of European printing, the curators reached out to institutions in the United States and Europe to borrow other rare items that would complete the story revealed through the exhibition — starting with early book production in Mainz, following the expansion of printing throughout Europe, and finishing with first editions of books by authors such as Virgil and Dante.

These loans were drawn from Cambridge University Library, the John Rylands Library of the University of Manchester, the Devonshire Collections in Chatsworth House, Columbia University Library, the Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary, the Morgan Library & Museum, New York Public Library, the Newberry Library, and the Bridwell Library of Southern Methodist University.

“They were amazingly cooperative. A positive response from everybody came quite quickly,” Needham said. “I have the impression that they caught on to the idea that including them in this particular exhibition made a strong reason to lend.”

Needham emphasized the University’s status as the only institution in the United States with the ability to provide the “critical mass” to which select loaned items could be added to mount an exhibition like this.

“Not even Morgan Library, Library of Congress, Huntington Library could have done this,” Needham said. “You would have to go to a place like the British Library in London or the Bibliotheque Nationale in France or the State Library in Vienna to find sort of an equivalent existing group of extremely rare, important early printing.”

“Princeton’s the best place to base this, and then to add the 20 loans made it historic,” White added. “There are a lot of little historical reunions going on in the glass cases. It’s wonderful to see them all together.”

The entrance to the Harvey S. Firestone Memorial Library.

Photo Credit: Jon Ort / The Daily Princetonian

For the curators, the books in the exhibition provide an unparalleled window into history. Lacking other records, the books themselves provide most of the information regarding where and how printing proliferated.

“Almost the only records we have are the books themselves, so it’s really the intensive study of these early printed books that enables us to draw a picture of the early years of the printed book trade,” Needham said. “These are the primary historical evidence. Although we don’t have the documents, from evidence in the books themselves, we can begin to reconstruct a network of trade.”

White expects that visitors may be surprised by how well-made and well-preserved the books themselves are.

“I think they were beautifully made for the centuries in their minds,” White said. “People don’t believe how beautiful these books are. How can the origins, the beginnings, not look sort of half-formed or primitive? How does it come out so well done?”

White and Needham believe there is something for everyone in the exhibit, and visitors needn’t be scholars to appreciate the items on display.

“Everyone who goes to this exhibit, whether they are deeply concerned with European typographic origins or not, will gain a respect for what people made more than five centuries ago,” White said. “They’re going to be struck by how beautiful and durable and careful these materials are, that people took time, took great effort, and dedicated their lives to making something useful, beautiful, and correct in a way that today, if something similar were made, it would be some sort of unique, go-it-alone craftsman doing a lost art.”

“Gutenberg & After,” on display through Dec. 15 at Firestone Library, is free and open to the public daily from noon to 6 p.m., including weekends.

An online version of the exhibit, featuring digitized images and in-depth descriptions, may be explored at dpul.princeton.edu.