The University Art Museum is currently featuring its first bilingual exhibit, “Miracles on the Border: Retablos of Mexican Migrants to the United States | Milagros en la frontera: Retablos de migrantes mexicanos a los Estados Unidos.” All titles, captions, descriptions, and online content related to the exhibit are offered in English and Spanish, thanks to the translation work of a University graduate student in the Department of Spanish & Portuguese.

The exhibit showcases ‘retablos,’ a form of devotional Mexican folk art created by unknown artists. Traditionally, those who had been delivered from crisis or danger would commission a retablo as an offering of thanksgiving to the holy figures who had provided salvation. These retablos then hung on the walls of churches and shrines.

Juliana Ochs Dweck, the curator of the exhibit and the museum’s Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Academic Engagement, described the idiosyncratic nature of the works, noting that “these objects are so many things at once.”

“They are sacred objects, but also they tell stories of everyday life,” Dweck said. “They’re personal objects — they’re objects that depict individuals, that share emotion, that show experiences from people’s lives — but they’re also presented in a public setting, in a church or a shrine. They are objects with religious value, representing holy figures, but here, they’re presented in an art museum.”

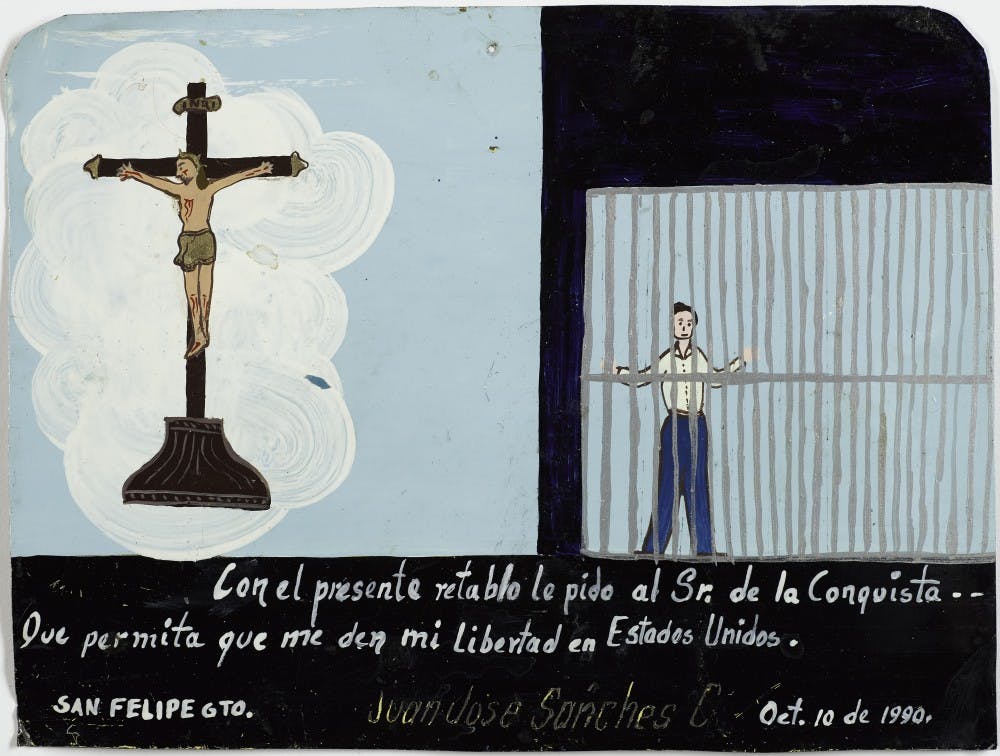

While each retablo depicts an individual story, the composition of the pieces is somewhat formulaic. In the lower register, a written inscription explains the details of the story surrounding the offering. Above it, the artist pictorially depicts the moment of crisis or thanksgiving. The artist also typically renders, in a standard iconographic style, one to three holy figures taking the form of the Christ, a saint, or the Virgin Mary — in the case of the retablos in the exhibit, often in her distinctly Mexican incarnation as the Virgin of San Juan de los Lagos, the holy figure most frequently called upon by Mexican migrants.

Though the tradition of retablos in Mexico began with the Spanish conquest of the 16th century, the pieces featured in “Miracles on the Border/Milagros en la frontera” span a period from 1917 to 1996 as they narrate stories of Mexican migration to the United States. Many of the exhibit’s retablos were commissioned by Mexican migrants returning home who wished to give thanks for having been delivered from difficult experiences migrating to and living in a foreign country, ranging from surviving near-fatal injuries to receiving an insurance check.

Displayed in chronological order, the retablos reveal a narrative of Mexican migration, providing a record of the shared and shifting concerns in Mexican migrant experiences. Earlier pieces show how the construction of the railroad initiated movement to the United States. The concerns of migrants gradually become more legalistic throughout the 20th century, and one of the most recent retablos depicts incarceration.

“They are incredibly powerful, delicate, intimate, multivocal paintings and objects that offer an incredible way to look at votive traditions and the stories of migrants,” Dweck said.

The 50 retablos on display in the Art Museum were collected by Douglas S. Massey, University Henry G. Bryant Professor of Sociology and Public Affairs, and Jorge Durand, Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Guadalajara.

Massey and Durand serve as co-directors of the Mexican Migration Project (MMP), a binational research effort initiated in 1982 which seeks to gain sociological and economic data on migration from Mexico to the United States. The MMP publishes its data on a public-use server and, according to Massey, is the largest and most reliable source of information on undocumented and documented migration from Mexico.

On a trip to the Church of San Juan de los Lagos in west-central Mexico, Massey and Durand discovered retablos relating to migration and thought the artworks could be used to analyze the experiences and the feelings of migrants to the United States.

Massey and Durand began collecting and photographing retablos in 1988, and in 1989, a small collection first debuted in a museum in Mexico City. The collection has now grown to a total of 58 retablos and travels all over the world.

The idea of bringing the exhibit to the Art Museum was originally conceived by University professor of comparative literature Sandra Bermann. Bermann is the coordinator of the University’s Migration Lab, a multidisciplinary research community founded in 2016 dedicated to examining issues of migration. Through the Migration Lab, Bermann became aware of Durand and Massey’s collection and the book which catalogued it, “Miracles on the Border.”

“The artworks shown there and the narratives that accompanied them were so moving and so beautiful that I thought they would be amazing to see on campus,” Bermann said.

Bermann approached James Steward, the Nancy A. Nasher-David J. Haemisegger, Class of 1976, Director of the Art Museum.

“I knew it was not the usual thing that appears in our art museum,” said Bermann, referencing the fact that the museum does not often show folk art and does not have a long history of featuring Mexican art. “But James seemed very eager to have exactly this kind of thing appear.”

Indeed, Steward noted that he found immense value in the exhibit as a display of underrepresented art as well as for its connection to previous projects with Bermann.

“I immediately embraced the material and the subject matter, both for its arresting quality — which can be thought of as a kind of modern folk art practice — as well as for its unexpected relationship to certain modernist practices, its relationship to the migrations project we mounted a year ago, and the opportunity to collaborate with Professor Bermann and her team once again,” wrote Steward in an email to The Daily Princetonian.

The exhibit is now presented in conjunction with the University’s Migration Lab.

The art pieces provide rich material for study from many disciplines, drawing visitors from Spanish classes, art classes, history classes, and local schools. The Migration Lab’s Mellon-Sawyer Seminar Series featured talks on topics such as the retablos’ religious significance, their historical context, and their influences on other modern artists, including Frida Kahlo.

Massey and Durand use the retablos to aid in their sociological research as the pieces provide a self-narrative of migration.

“When you’re a social scientist, you’re studying something and you’re explaining to other people about what an experience is like that you’re studying, and this was an opportunity to let the migrants tell us how they see the experience, what happens to them, what it was about from their point of view,” Massey said.

The bilingual nature of the exhibit is partly an effort to reflect this migrant perspective and provide a more direct experience to visitors who can read Spanish.

“[It] brings us insight: what do the migrants themselves feel? Not just what are we saying as sociologists or literary professors or whatever. But what are the people themselves saying?” Bermann said.

Dweck also emphasized the power of personal narratives.

“The migrants’ retablos allow us to humanize the experiences that we’re reading about in the newspaper in ways that are attentive to the individuals, and that give us insight into the lives behind the statistics,” she said.

Steward echoed Bermann’s sentiments, noting that he hopes the exhibition will inspire empathy and understanding among viewers.

“Beyond the obvious fact that the exhibition provides a certain historical context to a set of issues with remarkable topicality, I hope visitors will rediscover the power of the individual human voice, the fact that individual experience from decades ago, in some cases, lives on through these works, that they attest to the enduring qualities of hope, suffering, loss, the aspiration to a better life,” Steward wrote. “After all, isn’t that part of what good art does — it invites us into contact with and empathy for people whose lives and experiences past and present might be quite different from our own?”

“Miracles on the Border | Milagros en la frontera” will be on display at the Princeton University Art Museum through Sunday, July 7. More information about the exhibit, including information on all of the featured retablos, can be found on the museum’s website.