Compared to other universities, Princeton takes a unique approach toward student alcohol consumption. Although “Rights, Rules, and Responsibilities” makes clear that underage drinking is illegal, the University does not penalize inebriated students who are checked into McCosh Health Center. Instead, the University reserves disciplinary action against students who fail to “McCosh” one of their very drunk peers.

Yet, even this generous policy, which prioritizes the well-being of students, does not necessarily lessen students’ tendencies toward binge-drinking or irresponsible drinking behavior. And many other campuses treat underage drinking more harshly.

Take Miami University, touted as one of the biggest “party schools” in the United States. Bars surround the Oxford, Ohio, campus. During orientation for new students, police officers patrol popular bars, and several students are often suspended for underage drinking, even before they have started classes. According to one report, “students said when the university and city police try to curb the drinking through discipline it forces [them] to go underground to avoid getting caught or they become more defiant and drink more aggressively.” Rather than dissuading students from consuming large amounts of alcohol, the stigma encourages it

I believe that the issue isn’t as simple as a lack of responsibility on the part of underage drinkers — though, admittedly, they do not help their case by drinking. Rather, we must consider how the 21+ rule inadvertently contributes to underage drinking.

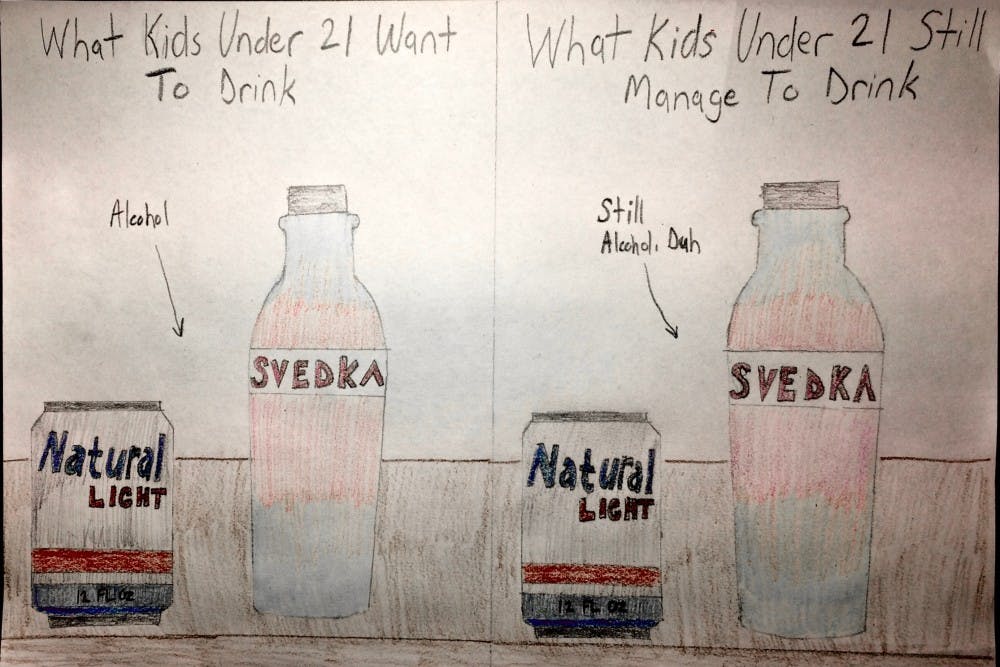

Restricting alcohol to people who are over 21 years old creates an unnecessary taboo. For someone under 21, much of the allure of drinking lies in the fact that a rule can be broken. The “you can’t stop me” attitude, particularly strong among teenagers, contributes to students’ illegal consumption of alcoholic beverages.

Their “rebellion” often goes too far, as many teens (especially those in high school) are inadequately equipped to drink responsibly and in moderation. Their overconsumption often occurs in secret. The mentality surrounding alcohol needs to change, and people should begin to view its consumption as a pleasurable, social, and occasional activity, rather than something to abuse in secret.

Thus, I believe that the age restriction concerning alcohol should be lowered to 18. Why? Because in almost every other respect, 18 year olds are considered adults. They can enlist in the Army, they can vote, and they can serve on a jury. Since an 18 year old can die for her country and have a say in the trajectory of her government’s leadership, it seems wildly inconsistent that she cannot likewise drink.

And, with the taboo on drinking lifted, perhaps teens, now regarded as “adult,” will be more obliged to make responsible decisions concerning alcohol. To prove this point, we can examine other countries where the age restriction is not so high.

France has a minimum drinking age of 18, but that’s only in public. Many children grow up seeing their parents regularly drink wine at meals, and sometimes even sip alongside them. One article notes that “countries where drinking wine at meals is standard, including Italy, France and Spain, rank among the least risky in a World Health Organization report on alcohol,” despite being some of the most alcohol-heavy nations.

Furthermore, the negative cultural perception of alcohol in the United States may provoke more dangerous drinking. The article also mentions that binge-drinking among college students in the US was significantly more severe than drinking among students at French universities.

Thus, we should consider how the lessons we teach our children regarding alcohol shape their perception of its consumption. While the University’s alcohol policy does much to preserve the well-being of students who have drunk too much, it does not necessarily encourage moderation or responsible drinking.

The policy cannot erase a taboo established in early childhood. Therefore, if education surrounding alcohol consumption is employed early on, and if parents demonstrate to their children that drinking in moderation is a normal, everyday act, perhaps children would be less anxious to get their hands on liquor and less likely to drink in excess. And, on a Princeton-specific note, if, as in France, children and teens are shown what “good” alcohol is — like having a sip of wine to complement your meal — they will be less likely to grab the first watered-down beer they see.

Emma Treadway is a first-year from Amelia, Ohio. She can be reached at emmalt@princeton.edu.