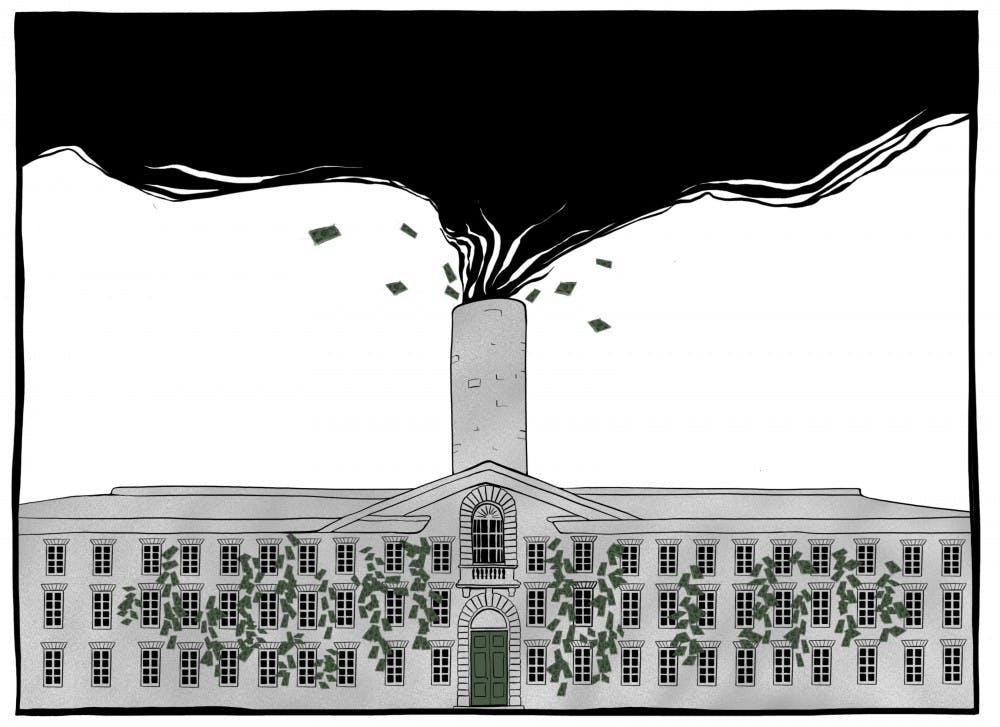

Since the anti-apartheid movement began in the 1960s, dozens of divestment campaigns have swept through Princeton’s campus. Yet more often than not, the University has chosen to deny student demands, including the push to divest from fossil fuels in 2015. It’s not like choosing to divest is an uncommon decision, either, especially with regard to climate change. Across the country, 48 U.S. universities have either partially or fully divested from fossil fuels. So why does Princeton consistently avoid shifting its investments?

After the 2015 fossil fuel divestment campaign was shot down, President Eisgruber voiced an opinion which he repeated again following the unsuccessful private prisons divestment campaign in 2017: that divestment is a political statement and that Princeton, in its efforts to maintain a neutral space open to diverse dialogue, should avoid “institutional position-taking.” While I agree that Princeton should allow differing opinions to be heard on campus, avoiding divestment because of its “political” nature is unreasonable and even hypocritical.

For starters, Princeton already makes several “political” statements on a regular basis. In 2017, for instance, Princeton filed a lawsuit against the federal government criticizing proposed DACA rollbacks, which would have directly affected one of Princeton’s students, María Perales Sánchez ’18. This past year, President Eisgruber signed on a letter to U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos condemning the proposed removal of protections for transgender people under Title IX because of the impact it would have on Princeton community members.

While these moves may seem to be more directly related to student well-being, the issues at the heart of divestment, like climate change, are also going to impact all of the Princeton community, some parts more disproportionately than others. Princeton’s history reflects the importance of these global divestment issues to campus life, too — the University has chosen to divest on two occasions, the first time in 1987 in relation to South Africa and apartheid and the second in 2006 with regard to the Darfur conflict. Thus, there is plenty of precedent when it comes to Princeton’s making political statements, and as long as the government continues to make decisions which affect student life, Princeton will need to perform the “institutional position-taking” which Eisgruber denounced in 2015.

In actuality, choosing not to divest in today’s politicized climate is just as much of a political statement as choosing to divest. By keeping our investments in fossil fuel companies, for instance, we’re sending a message to the world that we support the exploitative extraction of natural resources that not only are resulting in dangerous increases in global temperature but are also destroying local communities.

From the Dakota Access pipeline project, which would cut through the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, to the devastation of the Niger River Delta, where 70 percent of residents live below the poverty line, by Royal Dutch Shell oil spills, marginalized communities around the world are being damaged by fossil fuel infrastructure. Choosing a “business-as-normal” path a couple of decades ago may have been seen as neutral, but staying silent is no longer acceptable — instead, it’s a way of postponing the issue and letting others, those who have been shouldering the burden for years, deal with it.

Consider the results from the private prison divestment campaign that swept through campus this past year. The Resources Committee, a subset of the Council of the Princeton University Community, issued a statement that did not recommend divestment from private prisons because of a split vote. But isn’t issuing a statement against divestment just as political as issuing a statement for divestment? Yes, divestment is deeply rooted in public advocacy, but so is investment. Just as Princeton chooses to invest in fossil fuel companies, so too can it choose to invest in the renewable energy or green building industries.

Perhaps, then, student groups that want Princeton to change its investments would be more successful in the future if they promoted positive investment instead of, or in combination with, divestment. When used for good, investment can promote valuable growth and can also benefit us as an institution. Princeton has a commitment for the campus to be carbon-neutral by 2046, but in order to reach this goal, we’ll need to source our electric power from renewable sources — what better way to do so than to directly invest in the growth of local, clean energy, such as offshore wind in New Jersey?

New Jersey has also set a goal for an 80 percent reduction in greenhouse gases by 2050 from 2006 levels, contributing to the promotion of carbon-neutral power sources statewide, thus increasing the possibility for regional investment.

As more divestment campaigns emerge in the coming years, Princeton may choose to maintain an appearance of neutrality by choosing not to divest. Realistically, however, there is no such thing as neutrality in today’s society — whether Princeton divests or maintains its investments, they are always sending a political message. Moreover, by dismissing student divestment campaigns in favor of a “business-as-normal” approach, the administration is ultimately shutting down the diverse dialogue on campus which they originally intended to preserve through not divesting.

Instead of treating divestment with blanket contempt, I argue that the University should carefully examine how a “political statement” should be defined and whether pretending to “stay neutral” through not divesting is ultimately more harmful than expressing our institutional values through divesting our assets. Should the University acquiesce to every student call for divestment? Not necessarily. But if students bring forth well-researched arguments, the University should at least be more responsive to their concerns and critically evaluate how the decision it makes will be perceived and contextualized in the greater politicized environment in which we exist today.

Claire Wayner is a first-year from Baltimore, Md. She can be reached at cwayner@princeton.edu.